A lunchtime conversation between two men provokes a series of confrontations in Jun Robles Lana’s pressing psychological drama About Us But Not About Us. There is indeed more going on than it seems, prompting a number of questions about who it is that’s really in control along with the subjective quality of memory and personal myth making. After all as the younger of the men later says, nothing compares to our fictional counterparts both those we create for ourselves and those born of the projections of of others.

40-year-old professor Eric (Romnick Sarmenta) takes a look at the bags under his eyes in the mirror of his classic Beetle as he arrives at a restaurant for a lunch meeting with a student and gently applies moisturiser to his eyes before heading inside. It’s a small moment that hints at his insecurity about his age and also that he may have more interest in the student, Lance (Elijah Canlas), than he later claims. Lance is already waiting, perky and preppy in his neutral beige outfit and non-threatening haircut. The purpose of the meeting seems to be so that Lance can return the keys to Eric’s spare flat where he had being staying to escape an abusive stepfather. Lance no longer feels comfortable being there, in part because he’s afraid false rumours that there may be something inappropriate going on between them could cause problems for them both at the university, but also because he worries that his presence may have contributed to the suicide of Eric’s late partner Marcus, a leading light of English-language literature in the Philippines.

Marcus had known about Eric’s interest in Lance but warned him about becoming too involved seeing as he is a teacher and Lance his student not to mention that he is also 20 years older and even if he’s done nothing wrong others may read his well-meaning attempts to help as “inappropriate”. But then we start to wonder, is Lance really as helpless as he claims to be? It seems strange that a 22-year-old man would need this kind of rescuing, perhaps as some have suggested he’s constructed an image of himself as vulnerable so that Eric will feel compelled to help him. Despite his seeming meekness, Lance does appear to be ambitious yet insecure smarting from an offhand comment of Marcus’ that he may in the end lack the necessary talent to be accounted a writer.

In a theatrical conceit, Lana realises the projected images each has of the other to segue into recreations of previous meetings in which either Eric or Lance plays the role of the absent Marcus whose views are recounted only in the book he had written shortly before he died, his first in Filipino, or filtered through the memories and intentions of the other two men who of course may not be entirely honest in their recollections. Eric insists the problems that may or may not have existed between himself and Marcus were not not really “about” Lance. He claims to have been unhappy and emotionally neglected for years if also still in love, while later conceding that the book is both about and not about them in its retelling of a “trashy” love triangle as an intensely literary potboiler.

That the book is in Filipino rather than English may hint at a further desire for “authenticity”, as may Lance’s desire to transfer from the English department to that in his native language. Yet neither man is really being “authentic”, not entirely able to reclaim themselves from the image projected onto them by others. The battle for control shifts uneasily between them, Eric assuming he has the upper hand by virtue of his age and position all while Lance may be cynically manipulating him, playing on his latent desire while fluffing his ego in appearing as a lost young man in need of help and guidance. Even so, a possibly imagined conversation with Marcus later suggests that Eric enjoys the subversion and is at heart a masochist who actively seeks to be controlled, perhaps he knows what the game is after all. Lana ends on a note of ambiguity in which it seems there is a choice to be made between sustaining a fiction and rejecting it but then again “sometimes feelings are more important than the truth.”

About Us But Not About Us screened as part of this year’s Queer East .

Original trailer (English subtitles)

“Maybe it would be better if I just disappeared rather than physically be here but feel invisible all the time” the lonely heroine of Dwein Ruedas Baltazar’s Ode to Nothing (Oda sa wala) sadly laments to her only source of comfort, a semi-embalmed corpse. A melancholy meditation on the living death that is existential loneliness, Ode to Nothing takes its alienated heroine on a journey of hope and disappointment as she rediscovers a sense of joy in living only through befriending death.

“Maybe it would be better if I just disappeared rather than physically be here but feel invisible all the time” the lonely heroine of Dwein Ruedas Baltazar’s Ode to Nothing (Oda sa wala) sadly laments to her only source of comfort, a semi-embalmed corpse. A melancholy meditation on the living death that is existential loneliness, Ode to Nothing takes its alienated heroine on a journey of hope and disappointment as she rediscovers a sense of joy in living only through befriending death.

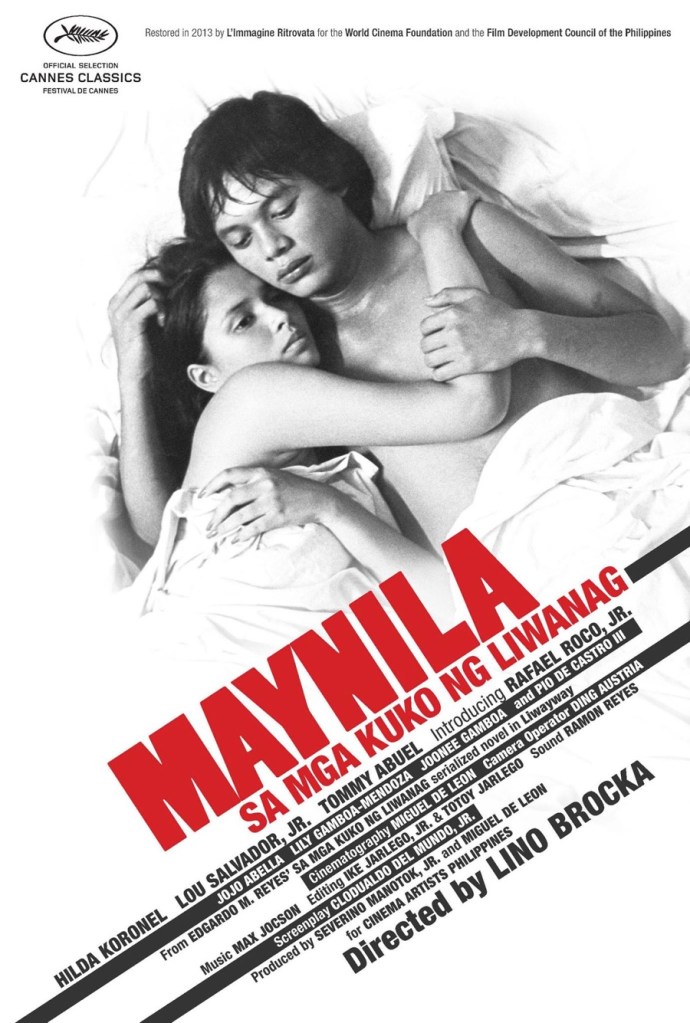

About half way through Lino Brocka’s masterpiece of Philippine cinema Manila in the Claws of Light (Maynila, sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag), the hero, Julio (Bembol Roco), sits watching the window where he thinks the woman he loves may be being held prisoner as a trio of guitar players strums out The Impossible Dream, unwittingly narrating his entire story. Julio is no Don Quixote but he has his own Dulcinea and, as the song says, without question or pause he is ready to march into hell for the heavenly cause of rescuing her from clutches of this cruel city. Not quite content to love pure and chaste from afar, Julio plays Orpheus descending into the underworld, plunged into a strange odyssey through a harsh and indifferent world driven by mutual exploitation and the expectation of violence.

About half way through Lino Brocka’s masterpiece of Philippine cinema Manila in the Claws of Light (Maynila, sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag), the hero, Julio (Bembol Roco), sits watching the window where he thinks the woman he loves may be being held prisoner as a trio of guitar players strums out The Impossible Dream, unwittingly narrating his entire story. Julio is no Don Quixote but he has his own Dulcinea and, as the song says, without question or pause he is ready to march into hell for the heavenly cause of rescuing her from clutches of this cruel city. Not quite content to love pure and chaste from afar, Julio plays Orpheus descending into the underworld, plunged into a strange odyssey through a harsh and indifferent world driven by mutual exploitation and the expectation of violence.