Cynical corporate spies find themselves in a battle of wits when one attempts to use the other in a psychedelic effort from Eiichi Kudo, Industrial Spy (産業スパイ, Sangyo Spy). A deliberate attempt to hop on to an ongoing trend sparked Bond mania and the success of Daiei’s “Black” series, along with the novels of Toshiyuki Kajiyama which inspired them, the film was intended as the first in a franchise vehicle for Tatsuo Umemiya whose Youth of the Night series had run out of steam.

As such, he stars as a jaded young man working as a corporate spy stealing trade secrets on behalf of rival companies. He does not infiltrate them by gaining employment, but makes use of connections, seducing women in administrative positions, and setting honey traps for blackmailing executives sometimes even using his own girlfriend Masami (Reiko Oshida). His main justification is consumerist desire. He tells Masami that if they want nice things they have to take them. They weren’t born with a silver spoon in their mouths, so they can’t afford to act refined and expect what they want to come to them. They have to do whatever it takes or resign themselves to a life of poverty. Masami, however, is beginning to tire of this arrangement and is hurt, more than anything else, when she realises that Kogure has only bought her a new handbag, necklace, clothes and shoes to head off his guilt because he’s about to ask her to sleep with the director of a project to create an experimental engine as part of a job he’s been manipulated into by Sawada (Fumio Watanabe), the head investigator of Nisshin Industries.

Rather childishly, Sawada convinces him to take the job basically by implying it’s too difficult for him. “There are secrets you just can’t steal,” he sighs, knowing that it’s like catnip to a man like Kogure who can’t resist a challenge even if he’s paying him less than a third of what he asked for. But Kogure has badly underestimated Sawada. When Kogure returns for his payment, he realises that Sawada sold the trade secrets back to the same company he stole them from to curry favour in the hope of worming his way in so he could take it over.

Both men are in differing ways unsatisfied with their circumstances. Kogure resents his poverty and wants to be allowed into the increasingly consumerist society of Japan’s high prosperity era, but at the same time he isn’t especially greedy. Sawada tells him he’s doing this because money alone is no longer enough for a man to live a full life in the modern era, he must obtain a powerful position too. All Kogure wants is to sleep with the woman he loves, eat good food, and have a good time. Which is to say he only wants to be comfortable rather than wealthy but feels that that life is unattainable to him outside of his current underhanded occupation. Poignantly, after asking Masami to sleep with his mark to obtain information, he realises that he actually does love her and resolves to marry her after the job is done. But for her this was the final straw and she only did as he asked so she’d hate him enough to leave.

Nevertheless, on learning he was tricked by Sawada, Kogure vows revenge by deliberately messing up Sawada’s plans to win a bid for a dam project on behalf of Nisshin by setting up a rival candidate and getting hold of their offer so they can make a better one. Only, Sawada always seems to be one step ahead and is even more ruthless than he is. While Kogure mourns Masami and is full of regret, pondering how he might win her back while his more straight-laced corporate lackey friend decides it’s time to shoot his shot, Sawada breaks up with his actual girlfriend to foil Kogure’s plan to photograph them together and blackmail him after he’s cynically married the disabled granddaughter of the Chuo Electric CEO who is mediating the dam bid. The older Mr Matsui (Takashi Shimura) is not completely blind to Sawada’s schemes, but blames himself for his granddaughter’s injury and believes it will be difficult for her to marry, so he’s willing to compromise himself corporately if only Sawada will ensure his granddaughter’s happiness.

Of course, that’s not really very high on Sawada’s list and only ever a means to an end. In this, he’s slightly different from Kogure who is equally heartless in some ways, humiliating a young woman who took an interest in him because she was of no use and he thought her cheap and vulgar, but clearly still has some vestige of human emotion even while realising he should probably let his friend chase Masami if he really loves her because she’s better off with him and his steady if dull corporate existence. In the end, though, neither man gets what he really wants and both ultimately lose out on both the money and the prize with Kogure vowing revenge against new enemies by whom he feels, a little unfairly, betrayed. Nevertheless, by ending with some monochrome stock footage of workers at the station, Anpo protestors being beaten by the police, and shots of US jet fighters, Kudo implies Kogure’s actions are a kind of rebellion against capitalism itself and the contemporary state of Japanese society even as he too becomes just another face in the crowd, an anonymous cog in this great shuffling machine.

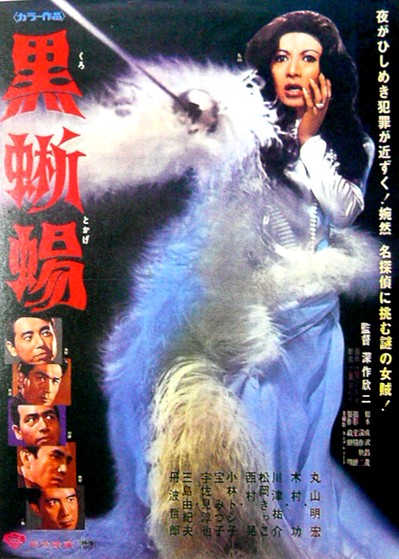

Those who only know Kinji Fukasaku for his gangster epics are in for quite a shock when they sit down to watch Black Rose Mansion (黒薔薇の館, Kuro Bara no Yakata). A European inflected, camp noir gothic melodrama, Black Rose Mansion couldn’t be further from the director’s later worlds of lowlife crime and post-war inequality. This time the basis for the story is provided by Yukio Mishima, a conflicted Japanese novelist, artist and activist who may now be remembered more for the way he died than the work he created, which goes someway to explaining the film’s Art Nouveau decadence. Strange, camp and oddly fascinating Black Rose Mansion proves an enjoyably unpredictable effort from its versatile director.

Those who only know Kinji Fukasaku for his gangster epics are in for quite a shock when they sit down to watch Black Rose Mansion (黒薔薇の館, Kuro Bara no Yakata). A European inflected, camp noir gothic melodrama, Black Rose Mansion couldn’t be further from the director’s later worlds of lowlife crime and post-war inequality. This time the basis for the story is provided by Yukio Mishima, a conflicted Japanese novelist, artist and activist who may now be remembered more for the way he died than the work he created, which goes someway to explaining the film’s Art Nouveau decadence. Strange, camp and oddly fascinating Black Rose Mansion proves an enjoyably unpredictable effort from its versatile director.