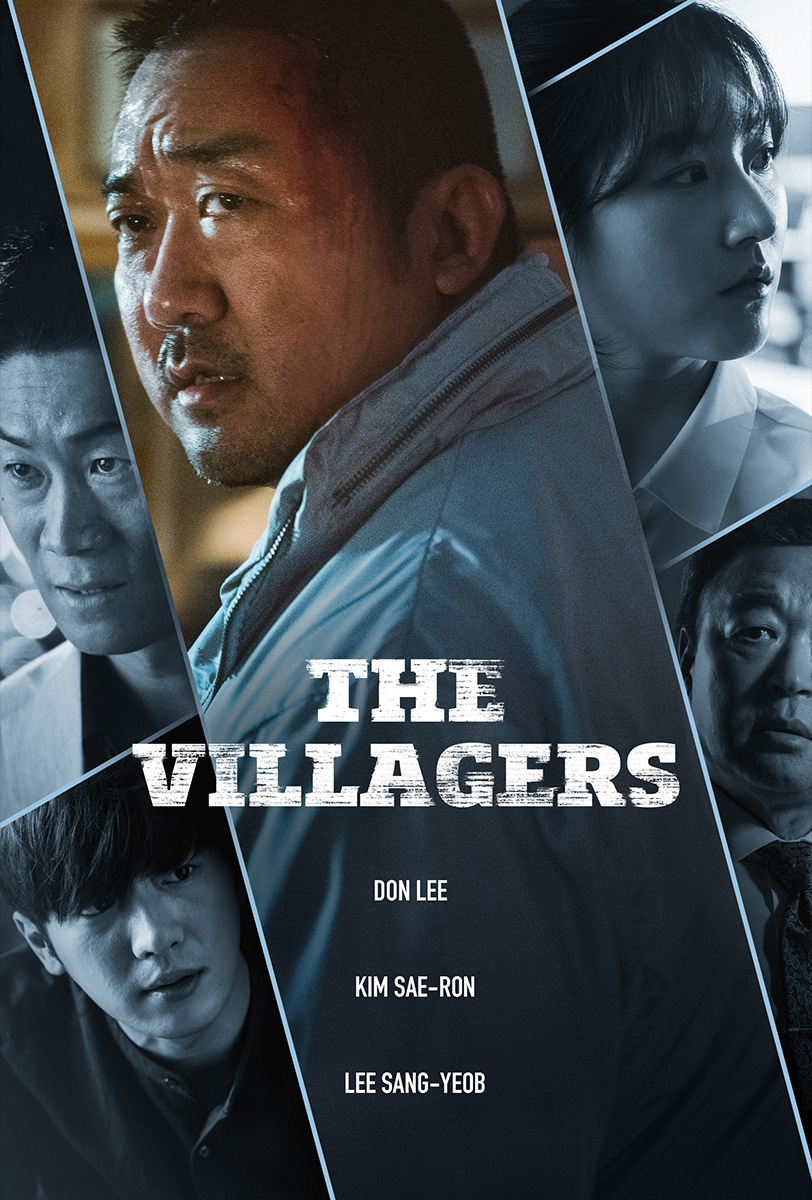

Trying to make a fresh start after being fired as a boxing coach in Seoul for challenging match fixing practices, a rookie teacher finds himself embroiled in small-town conspiracy in Im Jin-soon’s Ma Dong-seok vehicle, The Villagers (동네사람들, Dongnesaramdeul, AKA Ordinary People). Unlike the big bad city, this rural backwater is mired in feudalism and corruption as if it were stuck in the authoritarian past in which everyone keeps their head down and minds their own business rather than challenging injustice or trying to improve the lives of those around them.

What Ki-chul (Ma Dong-seok) and high schooler Yu-jin (Kim Sae-ron) have in common is that they’re both outsiders. Yu-jin transferred to the high school from Seoul and has been branded a troublemaker by the judgmental teachers. But despite the school’s seeming authoritarianism, the pupils have little respect for the school system and openly flout the rules by smoking on school premises and being rude to the staff. It transpires that Ki-chul has basically been hired as a kind of muscle, charged with getting students who haven’t paid their fees or dinner money to cough up ahead of an upcoming audit of the school’s finances. Many of the students he approaches brush him off as if they simply don’t intent to pay, but the school doesn’t seem to be interested in finding out why they might not be able to or if there are problems at home. Yu-jin too rolls her eyes he asks her, but in her case she’s unwilling to finance an institution that’s not doing anything for her even if as Ki-chul advises her they won’t let her graduate if she doesn’t.

Ki-chul seems uncomfortable with his new role and tries to do what he can to help, but encounters resistance from the teachers who tell him there’s no point worrying about kids like these. If they skip school, they’re branded runaways and no attempt is made to look for them. The teaching staff lowkey threaten Ki-chul by reminding him his job’s to get the money and he doesn’t want to make trouble for himself when he was lucky to be employed here in the first place. And so he finds himself conflicted when he spots Yu-jin in town getting herself into dangerous situations trying to find out what’s happened to her friend Su-yeon (Shin Se-hwi) who’s been missing for days but the police won’t seem to do anything. Yu-jin tells him that adults can’t be trusted, especially not the police, but he thinks it’s teenage alienation before trying to report the case again himself through a friend on the force and having it rejected.

The fierce resistance to even mentioning Su-yeon ought to tip them off that’s something bigger’s going on, but everyone is focussed on the upcoming election in which the headmaster of the school is standing for governor that nothing’s getting done at all. Ki-chul tries to report another teacher for harmful behaviour towards students, but is yelled at for exposing the school’s business by going to the police “over some runaway”. He’s reminded to keep his head down and mind his own business, even while Yu-jin continues to be in danger and Su-yeon is still missing. An orphan whose parents had massive debts to loansharks, Su-yeon was forced to work in a bar to support herself and her grandmother. She dreamed of being beautiful and free as an adult, but was badly let down by many of those around her including the school who decided that girls like her weren’t worth helping.

Of course, Ki-chul can’t help standing up for justice through the medium of his fists and smashing his way to the truth while trying to keep Yu-jin safe. If someone disappeared Su-yeon, they won’t think twice about doing the same to Yu-jin, though she of course thinks she’s invincible and is too young to think sensibly about her own safety while desperate to find out what’s happened to her friend. They are both, however, trapped by the legacy of an authoritarian era in which the police works only for the powerful and dirty local politics taints everything around it as everyone desperately tries to ingratiate themselves with the new regime while avoiding stepping out of line and endangering themselves. Ki-chul, however, has not much interest in that and is determined to smack some sense into gangsters and law enforcement alike in an effort to show that the world doesn’t necessarily need to be this way if only more people were willing to stand up to cronyism and exploitation.

The Villagers is released Digitally in the US Oct. 7 courtesy of Well Go USA.

Trailer (English subtitles)

Finding the sinister in the commonplace is the key to creating a chilling horror experience, but “finding” it is the key. Attempting to graft something untoward onto a place it can’t take hold is more likely to raise eyebrows than hair or goosebumps. The creators of Korean horror exercise Manhole (맨홀) have decided to make those ubiquitous round discs the subject of their enquiries. They are kind of worrying really aren’t they? Where do they go, what are they for? Only the municipal authorities really know. In this case they go to the lair of a weird serial killer who lives in the shadows and occasionally pulls in pretty girls from above like one of those itazura bank cats after your loose change.

Finding the sinister in the commonplace is the key to creating a chilling horror experience, but “finding” it is the key. Attempting to graft something untoward onto a place it can’t take hold is more likely to raise eyebrows than hair or goosebumps. The creators of Korean horror exercise Manhole (맨홀) have decided to make those ubiquitous round discs the subject of their enquiries. They are kind of worrying really aren’t they? Where do they go, what are they for? Only the municipal authorities really know. In this case they go to the lair of a weird serial killer who lives in the shadows and occasionally pulls in pretty girls from above like one of those itazura bank cats after your loose change.