In her 2006 documentary Dear Pyongyang, documentarian Yang Yonghi explored her sometimes strained relationship with her parents whose devotion to the North Korean state she struggled to understand. Her father having passed away in 2009, Yang returns to the subject of her family with Soup and Ideology (수프와 이데올로기) which is as much about division and how to overcome it as it is about her complicated relationship with her mother along with the buried traumas of mother’s youth as a teenage girl fleeing massacre and political oppression for a life in Japan marked by poverty and discrimination.

In animated sequence towards the film’s conclusion, Yang outlines the political history which led to the Jeju Uprising of 1948. Her mother Kang Junghi was born and raised in Osaka but when the city was all but destroyed in the aerial bombing of 1945, her parents decided to return to their hometown in Jeju. After the war, Korea was occupied by America and Russia and in 1948 an election was due to be held to ratify the upcoming divide. Ironically enough, the Jeju Uprising was a protest against division but brutally crushed by South Korean government forces resulting in a massacre in which over 14,000 people were killed. Then 18, Junghi lost her fiancé, a local doctor who went to fight in the mountains, and barely escaped herself walking 35km with her younger siblings in tow towards a boat which brought her back to Japan.

There are a series of ironic parallels in the lives of Yonghi and her mother, Yonghi forced to undergo a North Korean education with which she became increasingly disillusioned while her mother was educated in Japanese and obliged to take a Japanese name while living in a Zainichi community in Osaka. Near the film’s conclusion after Junghi has begun to succumb to dementia, she struggles to write her name in hangul on a visa needed to travel to South Korea but is able to recall it in Chinese characters, which also hang outside her home, perfectly. Meanwhile, Junghi was also parted from her family in tragic circumstances and left with a continual sense of absence and displacement. There is something incredibly poignant in seeing her at the end of her life surrounded by the ghosts family members who had long been absent, continually looking for her brother who moved to North Korea where he passed away, and asking for her late husband and eldest son who took his own life unable to adjust to the isolated Communist state where he was denied access to the classical music he loved.

Resolutely honest, Yonghi admits that she had little patience with her mother and saw her as a burden she cared for more out of obligation than love consumed with frustration and resentment towards Junghi’s devotion to North Korea and decision to send her three sons away leaving Yonghi a lonely child at home. An early scene sees her trying to confront her mother over her financial recklessness, pointing out that she is now retired and living on a pension. She can no longer afford to send the expansive care packages she prepared in Dear Pyeongyang which supported not only her sons and their families but whole communities in North Korea, while as Yonghi points out no one is going to be sending them after she passes away. Denied contact and company, these care packages were perhaps the best and only demonstration of maternal love available to her and the inability to send them is in its own way crushing.

Sending her brothers away, as she emphasises against their will, was the source of Yonghi’s resentment towards her mother yet on discovering the depth of her traumatic history as a survivor of the Uprising, Yonghi begins to understand, even if she does not condone, the various decisions her mother made throughout her life. Distrustful of the South Korean government having witnessed their treatment of ordinary citizens in Jeju while experiencing a hostile environment in Japan and forced to pick a side in the politicised environment of the Zainichi community, she sent her sons to North Korea ironically believing they would be safe from the kinds of horrors she encountered as a young woman. It is the literal, geographical and psychological division of Korea that lies at the heart of the divisions in Yonghi’s family dividing her ideologically from her parents and physically from her brothers while leaving Junghi orphaned in Japan

Banned from travelling to North Korea because of her previous films, Yonghi wonders how she will one day manage to deliver her mother’s ashes to their resting place next to her father in Pyongyang, but otherwise suggests that bridging the divide is possible not least in her marriage to a Japanese man, Kaoru, who adopts her mother almost as his own patiently taking care of her and learning the recipe for the traditional chicken soup she often makes stuffed with garlic from Aomori and generous quantities of ginseng. Touched by the sight of Junghi surrounded by photos of relatives she is unable to see, Kaoru tells Yonghi that even if they disagree politically they should make time to eat together peacefully as a family. A touching portrait of a difficult mother daughter relationship, Yang’s poignant documentary suggests there’s room for both soup and ideology and that divisions can be healed but only through a process of compassion and mutual understanding.

Soup and Ideology screens at the Korean Cultural Centre, London on 11th August as part of Korean Film Nights 2022: Living Memories.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Following on from the

Following on from the  Lee Byung-hun stars as a conflicted high school teacher who begins to see echoes of a woman he loved and lost years ago in a male student.

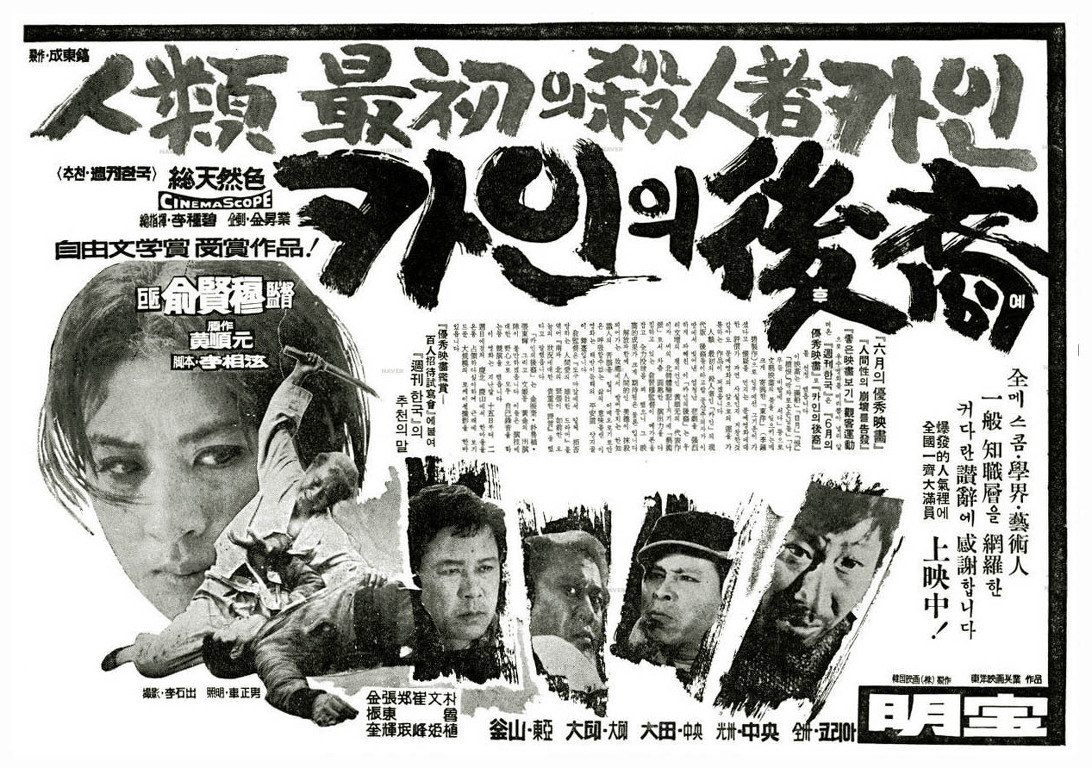

Lee Byung-hun stars as a conflicted high school teacher who begins to see echoes of a woman he loved and lost years ago in a male student. Kim Ki-young recasts the folly of war as a romantic melodrama in which a Korean conscript to the Japanese army receives harsh treatment from his sadistic superior but later falls in love with a Japanese woman.

Kim Ki-young recasts the folly of war as a romantic melodrama in which a Korean conscript to the Japanese army receives harsh treatment from his sadistic superior but later falls in love with a Japanese woman. Moon Jeong-suk stars as a determined young woman hellbent on becoming a judge in defiance of social convention which views marriage and motherhood as the only paths to female success. Encouraged by her father but forced to dodge her mother’s constant attempts to marry her off, she pursues her dream in spite of intense disapproval.

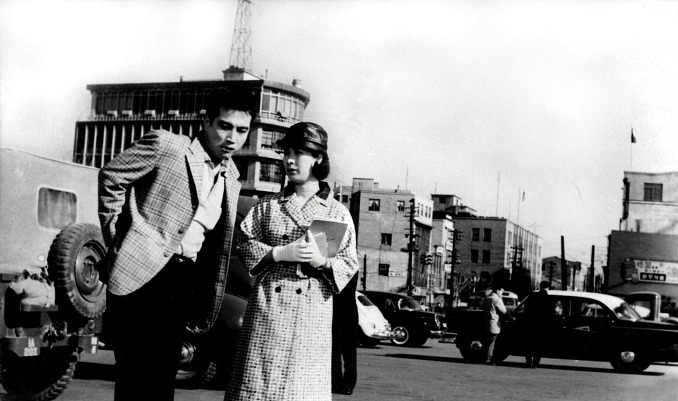

Moon Jeong-suk stars as a determined young woman hellbent on becoming a judge in defiance of social convention which views marriage and motherhood as the only paths to female success. Encouraged by her father but forced to dodge her mother’s constant attempts to marry her off, she pursues her dream in spite of intense disapproval. Kim Ki-duk (the old one!) draws inspiration from Ko Nakahira’s Dorodarake no Junjo for a tragic tale of love across the class divide as poor boy Du-su (Shin Seong-il) and Ambassador’s daughter Johanna (Um Aeng-ran) meet by chance and fall in love. Faced with the impossibility of their “pure” love in an “impure world” the pair find themselves an impasse, unable to reconcile their true feelings with the demands of the society in which they live.

Kim Ki-duk (the old one!) draws inspiration from Ko Nakahira’s Dorodarake no Junjo for a tragic tale of love across the class divide as poor boy Du-su (Shin Seong-il) and Ambassador’s daughter Johanna (Um Aeng-ran) meet by chance and fall in love. Faced with the impossibility of their “pure” love in an “impure world” the pair find themselves an impasse, unable to reconcile their true feelings with the demands of the society in which they live.  Im Kwon-taek’s “artistic breakthrough” stars Ahn Sung-ki as a young man who has abandoned his girlfriend and university studies to become a Buddhist monk but later meets an older man who indulges all of life’s Earthly pleasures such as wine and women.

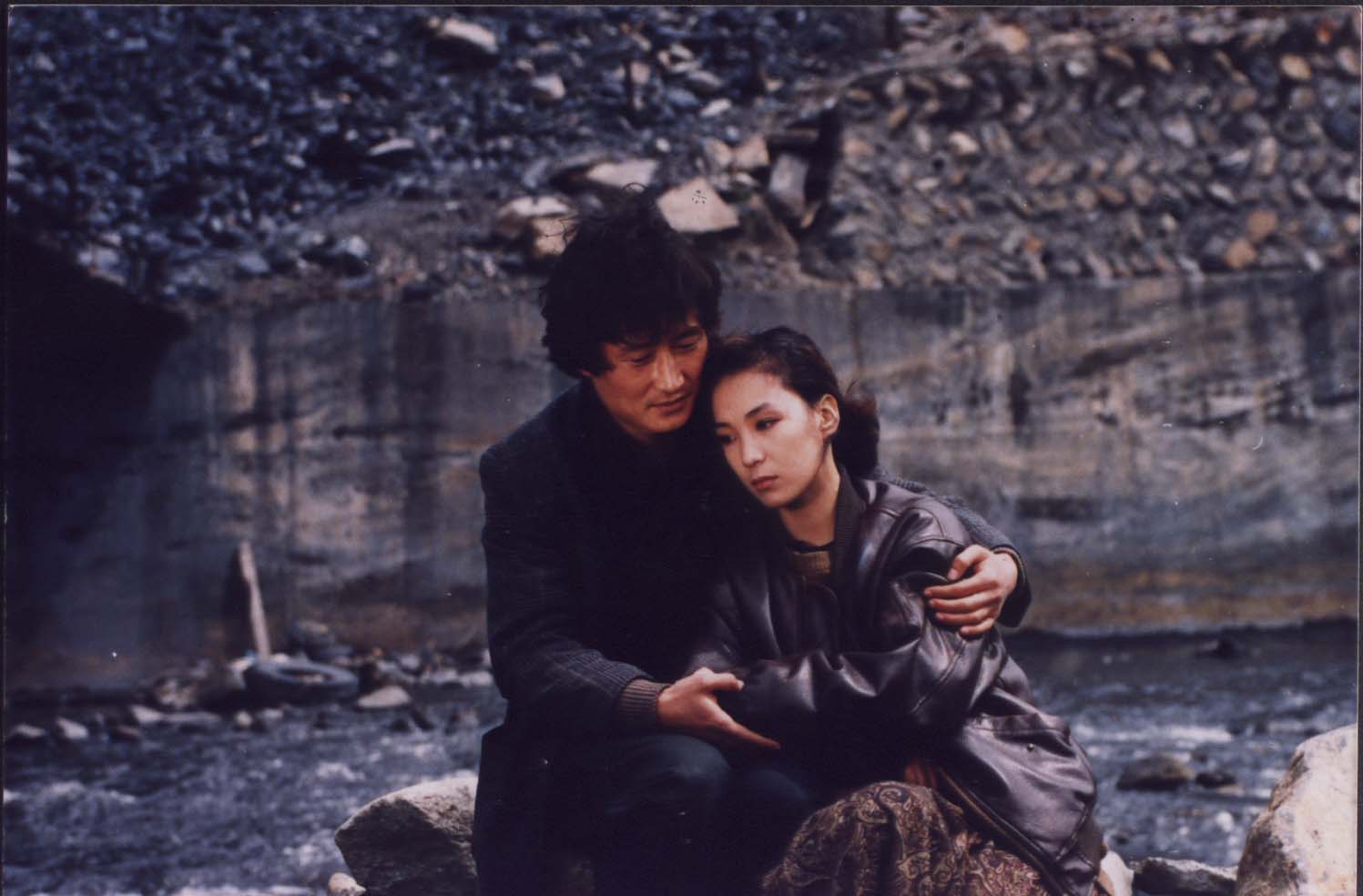

Im Kwon-taek’s “artistic breakthrough” stars Ahn Sung-ki as a young man who has abandoned his girlfriend and university studies to become a Buddhist monk but later meets an older man who indulges all of life’s Earthly pleasures such as wine and women. Park Kwang-su revisits the democratisation movement in its immediate aftermath as a student who hides from the authorities in a small mining village finds himself at odds with his environment while haunted by the possibility that his longed for revolution will not come to pass.

Park Kwang-su revisits the democratisation movement in its immediate aftermath as a student who hides from the authorities in a small mining village finds himself at odds with his environment while haunted by the possibility that his longed for revolution will not come to pass.

After a brief pause, the

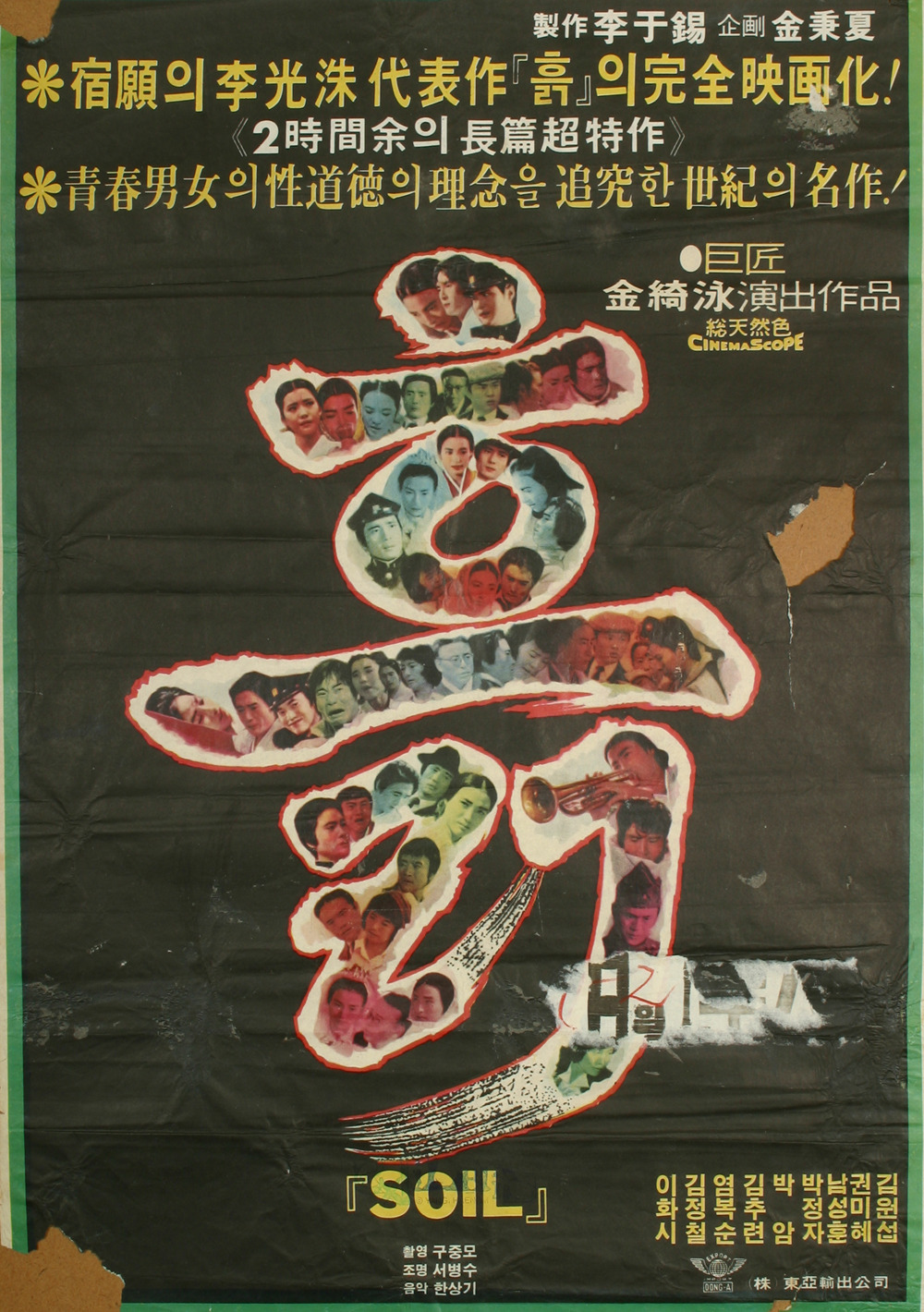

After a brief pause, the  Housemaid director Kim Ki-young adapts Yi Kwang-su’s 1932 novel of resistance in which a poor boy studies law in Seoul and marries the daughter of the landowner he once served only to decide to return and help his home village suffering under Japanese oppression.

Housemaid director Kim Ki-young adapts Yi Kwang-su’s 1932 novel of resistance in which a poor boy studies law in Seoul and marries the daughter of the landowner he once served only to decide to return and help his home village suffering under Japanese oppression.

Directed by Chung Ji-young, White Badge adapts Anh Junghyo’s autobiographical Vietnam novel in which a traumatised writer (played by Ahn Sung-ki) is forced to address his wartime past when an old comrade comes back into his life.

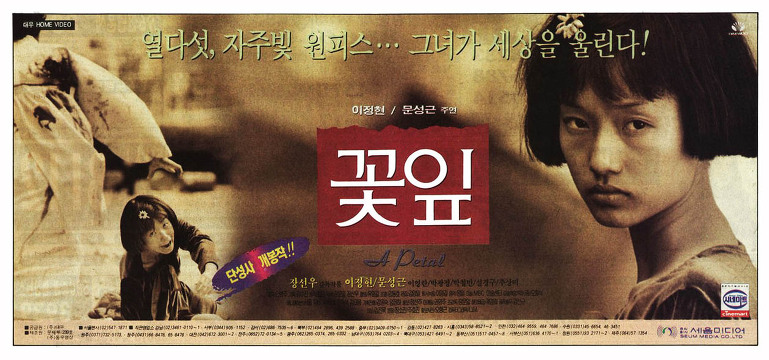

Directed by Chung Ji-young, White Badge adapts Anh Junghyo’s autobiographical Vietnam novel in which a traumatised writer (played by Ahn Sung-ki) is forced to address his wartime past when an old comrade comes back into his life. Adapting the novel by Choe Yun, Jang Sun-woo examines the legacy of the Gwangju Massacre through the story of a little girl who refuses to leave the side of a vulgar and violent man no matter how poorly he treats her.

Adapting the novel by Choe Yun, Jang Sun-woo examines the legacy of the Gwangju Massacre through the story of a little girl who refuses to leave the side of a vulgar and violent man no matter how poorly he treats her. Adapted from a novel by writer and activist Hwang Sok-young, Im Sang-soo’s The Old Garden follows an activist released from prison after 17 years who cannot forget the memory of a woman who helped him when he was a fugitive in the mountains.

Adapted from a novel by writer and activist Hwang Sok-young, Im Sang-soo’s The Old Garden follows an activist released from prison after 17 years who cannot forget the memory of a woman who helped him when he was a fugitive in the mountains. The debut feature from Kim Sung-je, the Unfair is an adaptation of Son Aram’s courtroom thriller which draws inspiration from the Yongsan Tragedy in which residents protesting redevelopment were forcibly evicted and several lives were lost including one of a police officer.

The debut feature from Kim Sung-je, the Unfair is an adaptation of Son Aram’s courtroom thriller which draws inspiration from the Yongsan Tragedy in which residents protesting redevelopment were forcibly evicted and several lives were lost including one of a police officer. An adaptation of the novel by Kim Ae-ran who will also be present for a Q&A, E J-yong’s My Brilliant Life stars Gang Dong-won and Song Hye-kyo as teenage parents raising a son who turns out to have a rare genetic condition which causes rapid ageing.

An adaptation of the novel by Kim Ae-ran who will also be present for a Q&A, E J-yong’s My Brilliant Life stars Gang Dong-won and Song Hye-kyo as teenage parents raising a son who turns out to have a rare genetic condition which causes rapid ageing.