The relationship between an artist and his muse (necessarily “his” in all but a few cases) is at the root of all drama, asking us if creation is necessarily a parasitical act of often unwilling transmutation. Osamu Tezuka’s Barbara (ばるぼら), brought to the screen by his son Macoto Tezka, takes this idea to its natural conclusion while painting the act of creation as a madness in itself. The hero, a blocked writer, describes art as a goddess far out of his reach, but also the cause of man’s downfall, framing his creative impotence in terms of sexual conquest that lend his ongoing crisis an increasingly troubling quality.

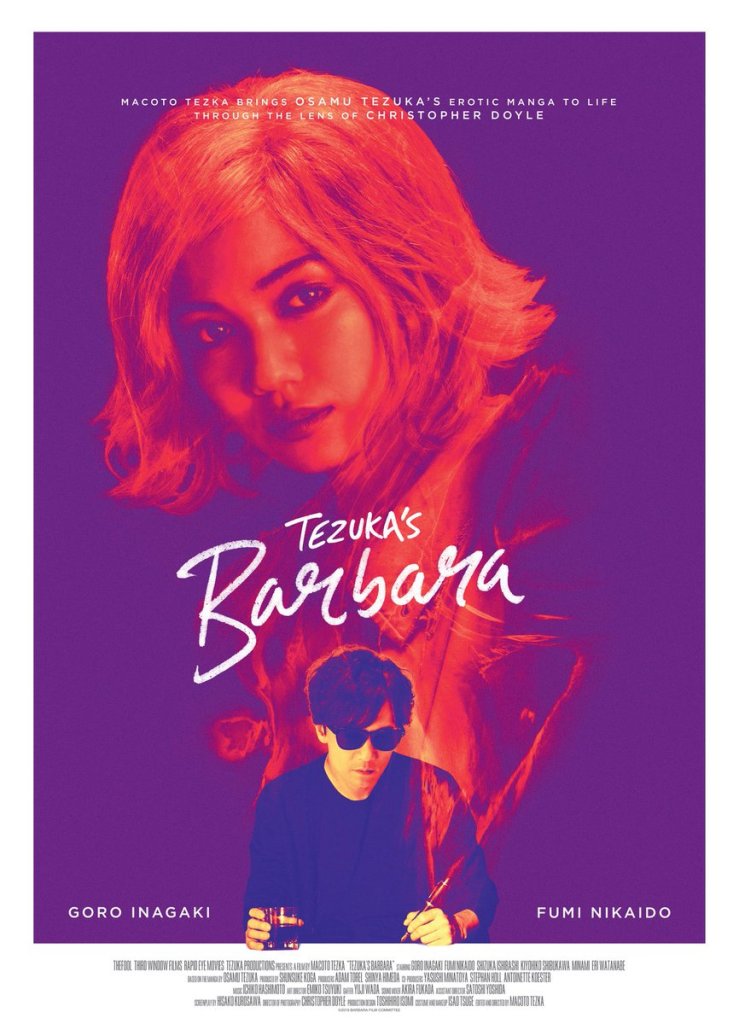

Yousuke Mikura (Goro Inagaki) was once apparently a well regarded novelist but has hit a creative block. While his friends and contemporaries are winning awards and national acclaim, he’s become one of “those” writers busying himself with potboilers and eroticism to mask a creative decline. Passing a young woman collapsed drunk in a subway, something makes him stop and turn back. Surprisingly, she begins quoting romantic French poetry to him, and actually turns out to be, if not quite a “fan”, familiar with his work which she describes as too inoffensive for her taste. Mikura takes her home and invites her to have a shower, but later throws her out when she dares to criticise an embarrassingly bad sex scene he’s in the middle of writing. Nevertheless, he’s hooked. “Barbara” (Fumi Nikaido) becomes a fixture in his life, popping up whenever he needs a creative boost or perhaps saving from himself.

Strangely, Barbara is in the habit of referring to herself using a first person pronoun almost exclusively used by men, which might invite us to think that perhaps she is just a manifestation of Mikura’s will to art and symbol of his destructive creative drive. He does indeed seem to be a walking cliché of the hardbitten writer, permanently sporting sunshades, drinking vintage whiskey, and listening to jazz while obsessing over the integrity of his art. We’re told that he’s a best-selling author and previously well regarded by the critics, but also that he has perhaps sold out, engaging in a casual relationship with a politician’s daughter and cosying up to a regime he may or may not actually support. He’s beginning to come to the conclusion that he’s a soulless hack and the sense of shame is driving him out of his mind.

Mikura’s agent Kanako (Shizuka Ishibashi) certainly seems to think he’s having some kind of breakdown, though the jury’s out on whether her attentions towards him are professional, sisterly, or something more. There isn’t much we can be sure of in Mikura’s ever shifting reality, but it does seem a strange touch that even a rockstar writer of the kind he seems to think he is could inspire such popularity, recognised by giggling women wherever he goes yet seemingly sexually frustrated to quite an alarming degree. His world view is an inherently misogynistic one in which all women seem to want him, but he can’t have them. A weird encounter in a dress shop is a case in point, the assistant catching his eye from the window display turning out to be a devotee of his work because of its “mindlessness”, something which annoys Mikura but only causes him to pause as she abruptly strips off for a quickie in the fitting room. Tellingly, the woman turns out to be an inanimate mannequin, literally an empty vessel onto which Mikura can project his fears and desires, which is, perhaps, what all other women, including Barbara, are to him.

Yet who, or what, is Barbara? Chasing his new “muse”, Mikura finds himself on a dark path through grungy subculture clubs right through to black magic cults, eventually arrested on suspicion of drug use. There is something essentially uncomfortable in his dependency, that he is both consuming and consumed by his creative impulses. Inside another delusion, he imagines himself bitten by potential love interest Shigako (Minami), as if she meant to suck him dry like some kind of vampire succubus, but finds himself doing something much the same to Barbara, stripping her bare, consuming her essence, and regurgitating it as “art”. Either an unwitting critique of the various ways in which women become mere fodder for a man’s creativity, or a meditation on art as madness, Barbara seems to suggest that true artistry is achieved only through masochistic laceration and the sublimation of desire culminating in a strange act of climax that stains the page with ink.

Tezuka’s Barbara screens in Amsterdam on March 6/7 as part of this year’s CinemAsia Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)