Students on a dance summer camp pick up a few lessons in authenticity and self-confidence while staying in an out of the way coastal hotel in Katsuhito Ishii, Shunichiro Miki, and Yuka Osumi’s goofy comedy Sorasoi (そらそい). Reuniting Ishii and Miki after Funky Forest, the film is less episodic in nature than the directors’ other work and quirky rather than surreal but otherwise offers some of the same lessons as those found in Party 7 as the students begin to discover new things about themselves and others while practicing dance on the beach.

Led by teacher Tabe (Sota Aoyama) who claims to have been a top dancer with the Royal Ballet before an injury ended his career, the dance team consists of four girls and three boys all of whom Tabe regards as no hopers with little motivation to succeed. A trio of men lounging in donuts floating nearby in the sea gently mock them from a distance, but nevertheless utter a few words of encouragement as they leave the beach. Meanwhile, another young woman, Yuri (Sayuri Ichikawa), arrives to stay at the hotel after approaching the local tourist information office and asking for a reservation at somewhere that isn’t listed in the phonebook.

Her request may echo that of Party 7’s Miki and her reasoning is similar in that she is clearly hoping to take some time out and doesn’t want to be bothered as evidenced by her decision to ignore missed calls and texts on her phone. The inn owner is forever trying to convince her to travel to a nearby beauty spot named the Cape of Love and its Lovers’ Bell though also dropping in casually that people sometimes take their own lives there which may be irresponsible given Yuri’s ambiguous mental state. In any case, she quickly catches the attention of student Ryu (Ryu Morioka) who begins pursuing her in a friendly if decidedly inappropriate way.

The three guys tell each other that they’re only doing dance to get girls and that the fact the ones from the dance troupe aren’t interested in them can be excused because they are “different”. Engaging in stereotypically crude male banter one of them later tries to steal the girls’ underwear but as it turns out, at least two of them do actually like dancing and discover new things about themselves in the midst of their romantic pursuits, Ryu’s for Yuri and Atsushi’s (Atsushi Yoshioka) for Kano (Kanoko Kawaguchi ), a mysterious kimono’d woman who arrives to visit. The girls meanwhile are similarly focussed on romance with Ai (Ai Makino) besotted with the grumpy teacher Tabe and Kikka (Kikka) dropping entirely unsubtle hints that she’s in love with the seemingly straight Mako (Masako Satoh) who thinks she’s just playing around.

They are all, however, keeping some kind of secret mainly because they fear being judged by others whether it relates to their sexuality, having embellished their CV, or having told a slightly bigger lie to help achieve their dancing dreams. What each of them learns is that it doesn’t matter very much if their dancing isn’t very good so long as they enjoy doing it and feel good about spreading that joy to others. Yuri, meanwhile, has some much more grown up dilemmas to consider especially as it transpires she may have been attempting to escape an abusive relationship with a degree of pressure placed on her from various directions to return because her boyfriend is “really a good guy” who made a “mistake” in a momentary fit of temper which is a fairly dated and uncomfortable sentiment to see presented so uncritically even in 2008. Nevertheless, the sense of discomfort is somewhat undercut in a counter courtship from Ryu who offers a sweet and romantic note that leaves the ball entirely in her court.

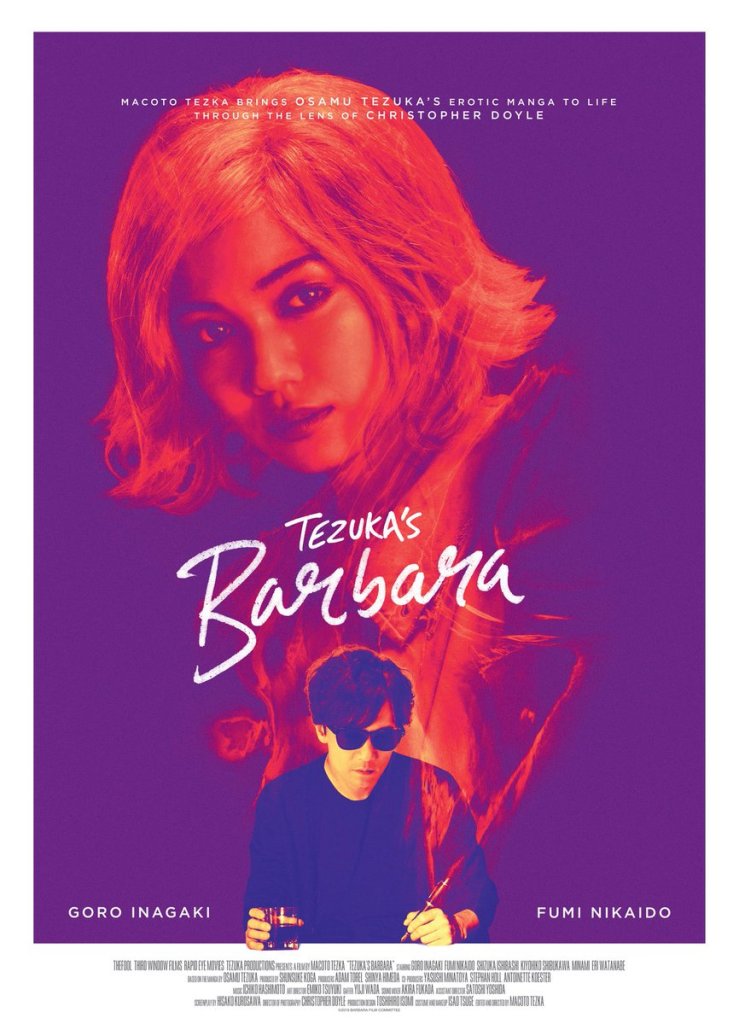

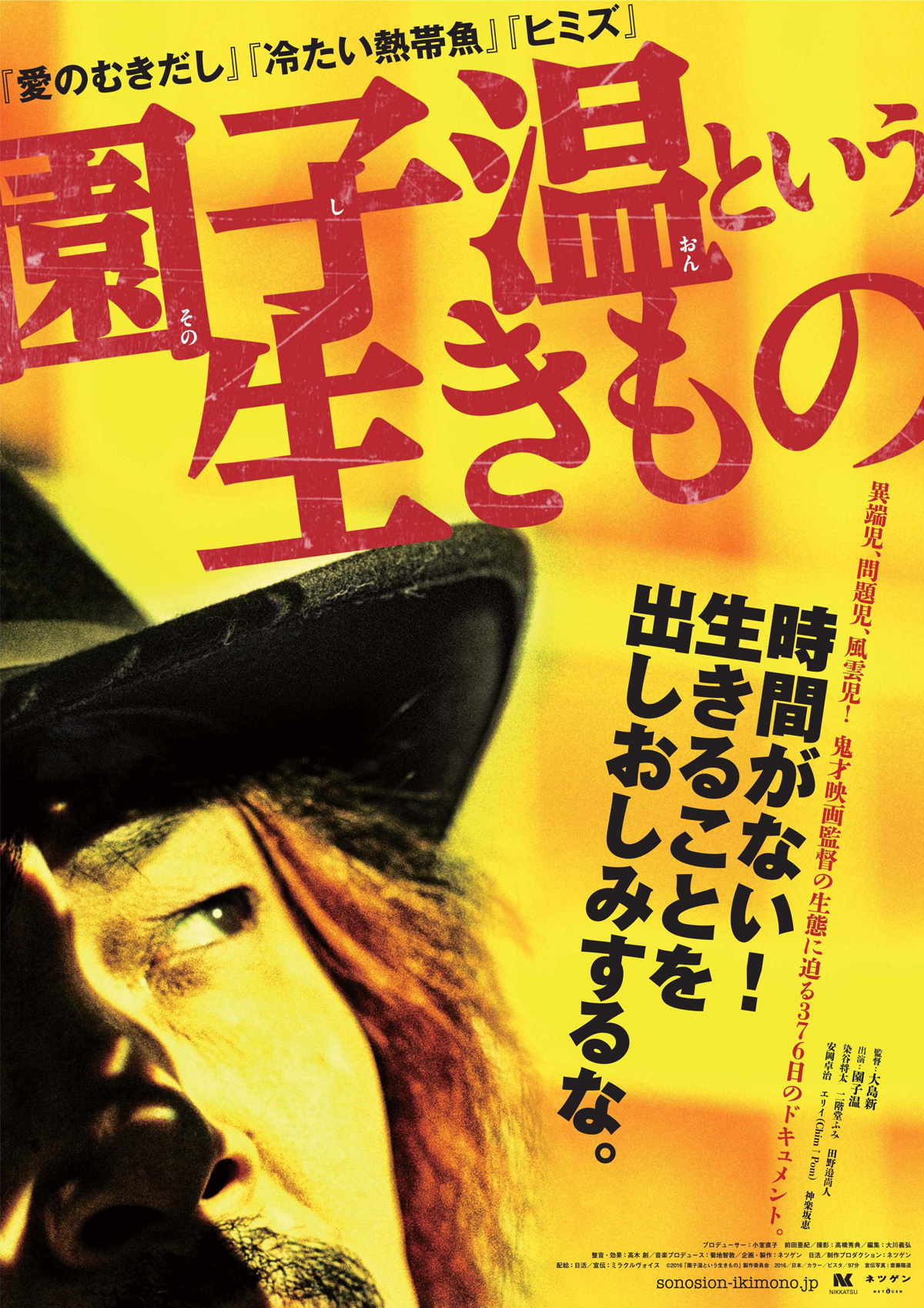

In the best tradition of summer break movies, the film’s relaxed atmosphere adds to its laidback charm as do the unfussy indie visuals while the enthusiastic performances from a largely amateur cast of students from Ishii’s acting school (bar the participation of Warped Forest’s Fumi Nikaido and Ryu Morioka) reinforce the central messages of working hard at something you love whether it goes anywhere or not. The mutual solidarity of those around them with similar dreams affords the students the confidence to be more of who they are while clarifying what it is they may actually want out of life even if for some the future still seems uncertain.

Sorasoi is released in the UK on blu-ray on 17th July as part of Third Window Films’ Katsuhito Ishii Collection.

Original trailer (English subtitles)