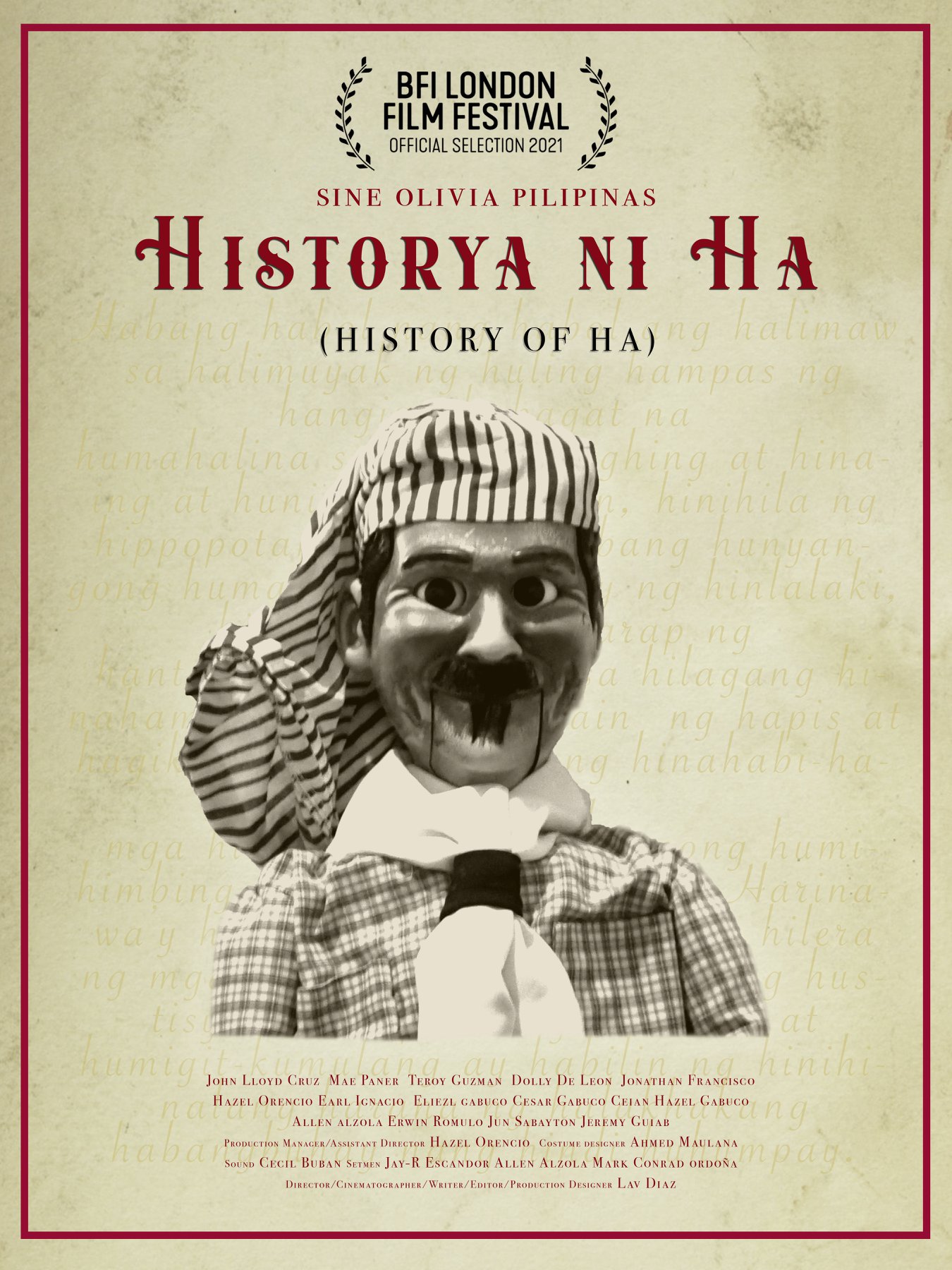

“We became victims of our time but I won’t let this situation destroy me” a wandering poet finally writes in a letter to his lost love, finding again a sense of purpose though having perhaps surrendered his illusions. Shot in a crisp monochrome and set ostensibly in 1957 but bearing several small anachronisms which bring us closer to the present day, Lav Diaz’ 4-hr absurdist fable History of Ha (Historya ni Ha) finds an exile returning in the hope of a more peaceful future only to find his dreams of a simple life dashed while the land is once again in turmoil. An exploration of lingering feudalism, its links to dangerous demagoguery, and the ease with which populist leaders manipulate despair, Diaz’ timely drama sees its hero once again a self-exile but resolving at least to sow the seeds of a better future in work and education.

Four years previously, disillusioned marxist poet Hernando (John Lloyd Cruz) was arrested with the Socialists after the failure of the Huk Rebellion and has since been touring Asia as a successful vaudeville act in the company of his ventriloquist puppet, Ha. Having saved enough money, he’s retired from showbiz and is heading home to marry his sweetheart, Rosetta, to whom he is writing while on the boat. The first sign of trouble begins, however, when Hernando is approached by a journalist who happens to be a fan and invites him to dine with a congressman. President Magsaysay, the anti-communist president backed by the US, is missing later to be declared dead in a plane crash. Though presumably no fan of Magsaysay, Hernando worries for his country recalling a song penned by a civil servant suggesting that should Magsaysay die democracy would go with him.

The journalist is equally ambivalent, describing Magsaysay’s rise as a mix of reality and myth making, a cycle he fears will repeat itself endlessly in the history of the Philippines in which “the masses will vote for false prophets and leaders”. Hernando, meanwhile, discovers on his arrival home that not everything is as he left it. Though Rosetta had been writing to him earnestly throughout his travels, his twin sister Hernanda (Gabuco Eliezl) tells him that following the death of her mother she has become a prisoner of her father’s house and is to be married to a local nobleman in payment of a debt. Her final letter confirms this to be true, instantly shattering his belief in future possibility while raging against the lingering feudalism of the post-war nation. “I’ve accepted that as long as a powerful few possesses the vast lands of this barrio the poor will remain sinking in poverty and helplessness” , he explains heading out on an aimless journey no longer speaking directly but only through his dummy, Ha.

Ha becomes in a sense his alter ego, voicing what he himself cannot say, but also giving rise to a sense of absurdity as those around him begin to invest in Ha’s personhood talking directly to him rather than Hernando while asking him incongruous questions even wondering if he might be hungry. Yet much of Ha’s monologuing is pure nonsense rhyme, and while the pair of them are alone he sometimes reflects Hernando’s inner cynicism suggesting he accept money from a pair of women he reluctantly agreed to help travel to a nearby fishing village from which they hope to gain passage to an island in the middle of a gold rush, one a nun intending to start a mission (Mae Paner) and the other a woman wanting to open a business (Dolly De Leon). A boy he’d met along the way, Joselito (Jonathan O. Francisco), had the same destination in mind, explaining that there was no other way to alleviate his family’s poverty. When they arrive at the village, however, they discover that the journalist’s prognosis was painfully true. The self-appointed leader of the settlement, Among Kuyang (Teroy Guzman), is a narcissistic populist harping on nationalism while mercilessly exploiting the desperation of the less fortunate in charging impossible sums for transportation.

Ha advises the trio not to go, fearing that the island is dangerous, but fails to dissuade them, the difficulty of living under Among Kuyang’s repressive regime only increasing their desire to leave. Eventually he decides to help them by performing one of his old shows for Kuyang who turns out, uncomfortably, to be a fan, but worries he may have “saved them from the devil but delivered them to hell”. “It hurts how we let people like him rule over our country” another failed revolutionary laments, while Kuyang himself offers prophesies of Marcos and Duterte, echoing this ugly cycle of myth making and deception which just as he has weaponises desperation while doing nothing to alleviate it. Yet in his cynicism perhaps Hernando too is guilty of belittling the masses, declaring them too ignorant to understand their oppression. “Their emptiness is not their fault, sacrifices are not enough to emancipate them.” he laments, while echoing the journalist that decades from now they’ll go on “enthroning despots and tyrants, leaders like Among Kuyang, leaders who are foolish, greedy, disrespectful, deranged”.

Ironically enough he tries to be the “good cat” of the story Ha had told his niece and nephew, cautioning them against populist and consumerist fallacy in warning them not to walk into a golden cage and thereby lose their freedom, but to accompany the good cat to the shore and salvation. Hernando tries to save the trio from the lure of the island, sure it promises only fruitless exploitation, but fails to save them from Among Kuyang or from the true enemy which is ceaseless poverty, a sense of futility, and feudal privilege. “Gold is not the only solution to poverty” he’d told Joselito, but to him it was all that was left. Beginning and ending with a letter, Diaz’ absurdist parable follows its disillusioned hero through loneliness and tragedy but finally allows him to find the boat that grants him freedom if only in new purpose in undermining the roots of populism where they first propagate.

History of Ha made its World Premiere as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival.

Original trailer (dialogue free)

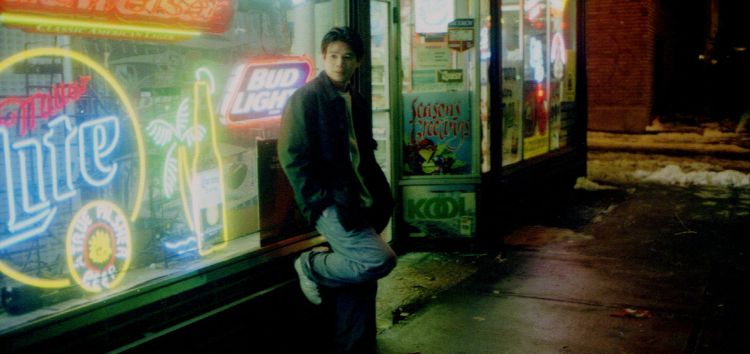

Lav Diaz’s auteurist break through, Batang West Side is among his more accessible efforts despite its daunting (if “concise” by later standards) five hour running time. Ostensibly moving away from the director’s beloved Philippines, this noir inflected tale apes a police procedural as New Jersey based Filipino cop Mijares (Joel Torre) investigates the murder of a young countryman but is forced to face his own darkness in the process. Diaspora, homeland and nationhood fight it out among those who’ve sought brighter futures overseas but for this collection of young Filipinos abroad all they’ve found is more of home, pursued by ghosts which can never be outrun. These young people muse on ways to save the Philippines even as they’ve seemingly abandoned it but for the central pair of lost souls at its centre, a young one and an old one, abandonment is the wound which can never be healed.

Lav Diaz’s auteurist break through, Batang West Side is among his more accessible efforts despite its daunting (if “concise” by later standards) five hour running time. Ostensibly moving away from the director’s beloved Philippines, this noir inflected tale apes a police procedural as New Jersey based Filipino cop Mijares (Joel Torre) investigates the murder of a young countryman but is forced to face his own darkness in the process. Diaspora, homeland and nationhood fight it out among those who’ve sought brighter futures overseas but for this collection of young Filipinos abroad all they’ve found is more of home, pursued by ghosts which can never be outrun. These young people muse on ways to save the Philippines even as they’ve seemingly abandoned it but for the central pair of lost souls at its centre, a young one and an old one, abandonment is the wound which can never be healed. If

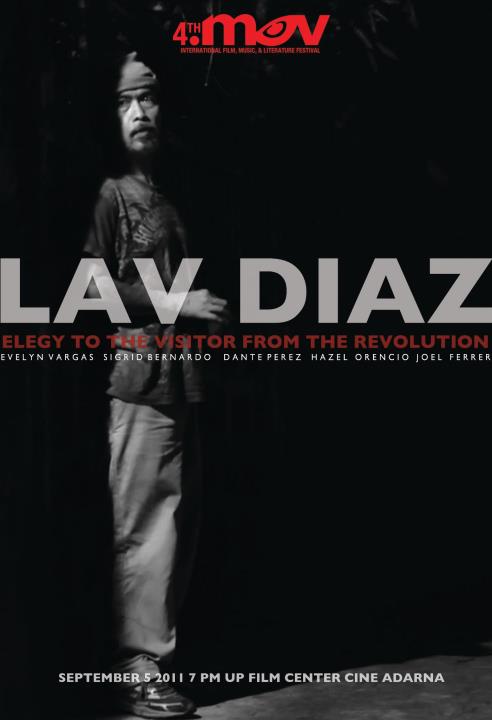

If  Lav Diaz is many things but he’s not especially known for his brevity. Elegy to the Visitor From the Revolution (Elehiya Sa Dumalaw Mula Sa Himagsikan) is something of a departure in that regard as it runs a scant eighty minutes but is, nevertheless, imbued with the director’s constant themes of loss, melancholy and despair conveyed across a tripartite structure peopled by three very different yet interconnected sets of characters. To say “only” eighty minutes long, yet Elegy to the Visitor From the Revolution first began as a one minute short, intended to form a part of Nikalexis.MOV – an omnibus dedicated to the memory of film critics Alexis Tioseco and Nika Bohinc tragically killed during a home invasion. Diaz’ film, however, outgrew its origins to become a stand alone feature in its own right.

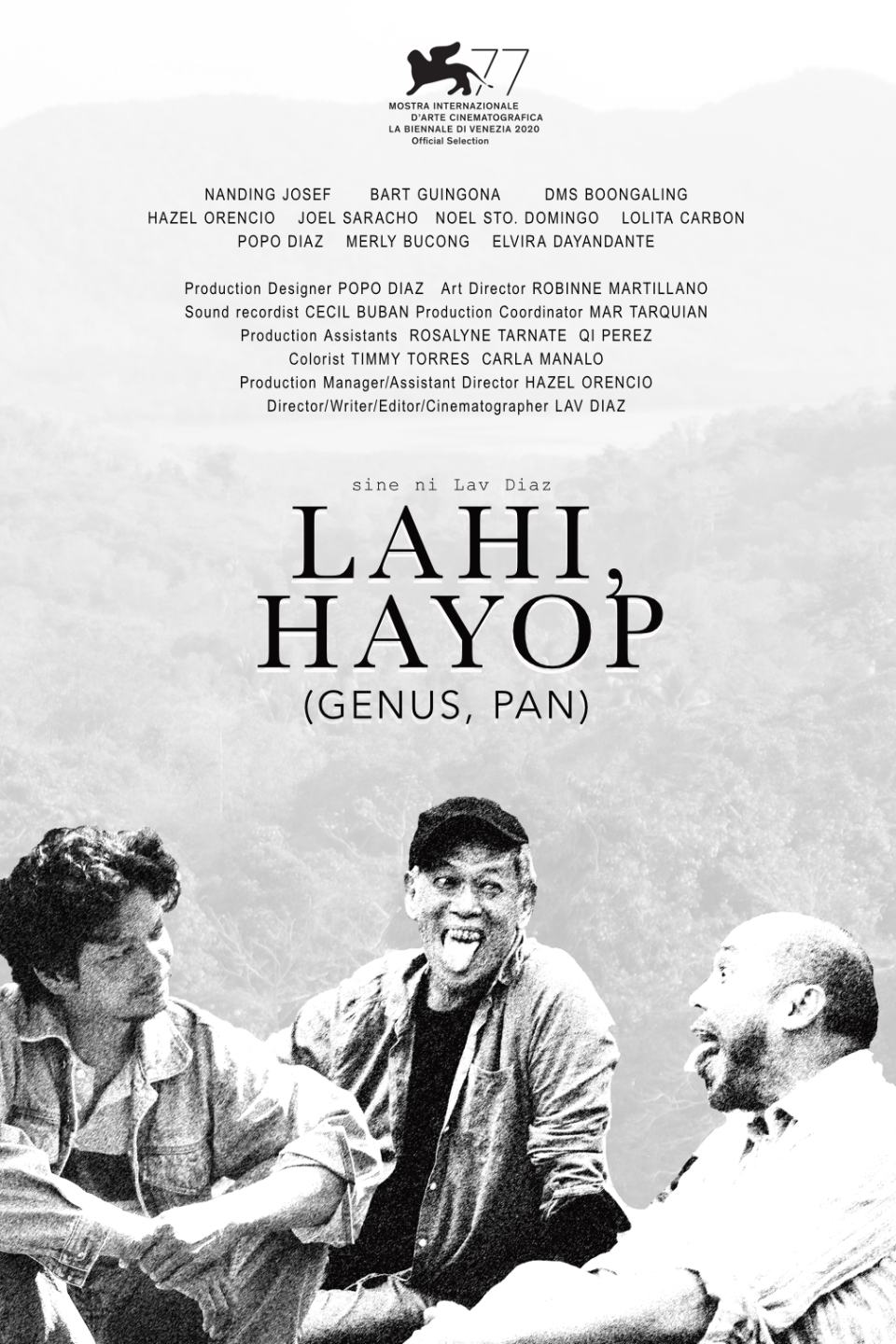

Lav Diaz is many things but he’s not especially known for his brevity. Elegy to the Visitor From the Revolution (Elehiya Sa Dumalaw Mula Sa Himagsikan) is something of a departure in that regard as it runs a scant eighty minutes but is, nevertheless, imbued with the director’s constant themes of loss, melancholy and despair conveyed across a tripartite structure peopled by three very different yet interconnected sets of characters. To say “only” eighty minutes long, yet Elegy to the Visitor From the Revolution first began as a one minute short, intended to form a part of Nikalexis.MOV – an omnibus dedicated to the memory of film critics Alexis Tioseco and Nika Bohinc tragically killed during a home invasion. Diaz’ film, however, outgrew its origins to become a stand alone feature in its own right. “Why is there so much madness and too much sorrow in the world? Is happiness just a concept? Is living just a process to measure man’s pain?” asks a key character towards the end of this eight hour film, but he might as well be speaking for the film itself as its director, Lav Diaz, delivers another long form state of the nation address. This is a ruined land peopled by ghosts, unable to come to terms with their grief and robbing themselves of their identities in an effort to circumvent their pain. Raw yet lyrical, Diaz’s lament seems wider than just for his damaged homeland as each of its sorrowful, disillusioned warriors attempts to reacquaint themselves with world devoid of hope.

“Why is there so much madness and too much sorrow in the world? Is happiness just a concept? Is living just a process to measure man’s pain?” asks a key character towards the end of this eight hour film, but he might as well be speaking for the film itself as its director, Lav Diaz, delivers another long form state of the nation address. This is a ruined land peopled by ghosts, unable to come to terms with their grief and robbing themselves of their identities in an effort to circumvent their pain. Raw yet lyrical, Diaz’s lament seems wider than just for his damaged homeland as each of its sorrowful, disillusioned warriors attempts to reacquaint themselves with world devoid of hope. Lav Diaz has never been accused of directness, but even so his 8.5hr epic, Heremias (Book 1: The Legend of the Lizard Princess) (Unang aklat: Ang alamat ng prinsesang bayawak) is a curiously symbolic piece, casting its titular hero in the role of the prophet Jeremiah, adrift in an odyssey of faith. With long sections playing out in near real time, extreme long distance shots often static in nature, and black and white photography captured on low res digital video which makes it almost impossible to detect emotional subtlety in the performances of its cast, Heremias is a challenging prospect yet an oddly hypnotic, ultimately moving one.

Lav Diaz has never been accused of directness, but even so his 8.5hr epic, Heremias (Book 1: The Legend of the Lizard Princess) (Unang aklat: Ang alamat ng prinsesang bayawak) is a curiously symbolic piece, casting its titular hero in the role of the prophet Jeremiah, adrift in an odyssey of faith. With long sections playing out in near real time, extreme long distance shots often static in nature, and black and white photography captured on low res digital video which makes it almost impossible to detect emotional subtlety in the performances of its cast, Heremias is a challenging prospect yet an oddly hypnotic, ultimately moving one.