The Korea of 1959 was one of change, but the hardest thing to change is oneself and oftentimes the biggest obstacle to personal happiness is the fear of pursuing it. The pure hearted heroine of Shin Sang-ok’s Dongsimcho (동심초) describes herself as “a woman who thirsts for love, yet foolishly gives in to fear first”. A war widow, she’s fed up with society’s constant prejudice but too afraid of what they might think if she chose to choose love, embrace her desire, and marry again for no other reason than personal happiness. Yet for all that she’s a mother with a grown up daughter, she’s a woman too, and young, only 38, but nevertheless consigned to a life of loneliness because of a series of outdated social codes.

When we first meet Suk-hee (Choi Eun-hee) she’s rushing to the station but arrives too late and can only watch the man she loves board a train through an iron gate that perpetually divides them. Her husband having died in the Korean War, Suk-hee once had a dress shop but was conned out of all her money and the business failed. The kind hearted brother of a friend, Sang-gyu (Kim Jin-gyu), helped her out. Through the course of his managing her affairs, they became close and fell in love, but Sang-gyu is now engaged to the boss’ daughter, Ok-ju (Do Keum-bong), and their romance seems more impossible than ever.

Suk-hee never quite dares to hope that Sang-gyu might break off his engagement, decide against a bright middle-class future, and start again with her. She’s an old fashioned kind of woman. Despite the fact she once owned a dress shop, she only ever wears hanbok and lives in an improbably spacious Korean-style house alone with her college student daughter, Kyeong-hee (Um Aing-ran), and a maid. The debt that exists between herself and Sang-gyu is the force that both binds them and keeps them apart. The money rots their relationship, but neither of them want it to be repaid because then they’d have no more excuse to continue meeting. They are both perfectly aware of each other’s feelings but entirely unable to acknowledge them because in some sense they already know that their future is impossible.

On discovering her mother’s “secret”, Kyeong-hee is mildly scandalised, confronted by the realisation that a mother is also a woman just as she is now. She worries about the moral ambiguities of her mother’s position and of what people might say, but quickly reconsiders, deciding to be happy for her and actively support her chances of a happier future. As a younger woman coming of age in the post-war era, Kyeong-hee feels freer to shake off social convention and strike out for personal happiness rather than being content to be miserable while upholding a series of social codes which lead only to additional suffering.

Only slightly younger than Suk-hee, Sang-gyu is beginning to feel the same. His widowed older sister, Suk-hee’s friend, has turned to religion to escape her loneliness while staking all of her hopes on Sang-gyu’s economic success. It’s she who’s set him up with the marriage to Ok-ju and is pressuring him to accept it because it will assure her own future seeing as she is obviously not planning to defy convention and remarry. Sang-gyu, however, is filled with doubts. Eventually he tells his associate, Gi-cheol (Kim Seok-hoon), that he cannot go through with the marriage, adding that he doesn’t want advice or a warning he merely needed to tell someone. In a strange coincidence, Gi-cheol was once Kyeong-hee’s tutor, and has a surprisingly conservative attitude. Questioned by Ok-ju, he tells her to “act more lovingly” to cure Sang-gyu’s obvious lack of enthusiasm for their relationship, explaining that love doesn’t just happen but is a result of concerted effort. He tells Sang-gyu that he’s being childish and irresponsible and should think about “social ethics and morality”. In short, he should forget about the past and marry Ok-ju like a good boy. But Sang-gyu quite reasonably asks him who’s going to be responsible for what happens after that. If he marries Ok-ju now, he will merely be condemning her to a cold and loveless marriage filled with intense resentment in which the spectre of the woman he loved and lost will always stand between them.

Kyeong-hee unexpectedly arrives part way through the conversation having followed Gi-cheol with whom she has perhaps also begun to fall in love despite the difference in their attitudes. She jumps in to defend Suk-hee, taking Sang-gyu’s side in berating Gi-cheol for insulting her mother, asking if he thinks a woman like her has no worth. Her mother is a woman too, and though she was originally confused and scandalised, after getting to know Sang-gyu and giving it some thought she’d like to give them her blessing though of course they don’t need it. Kyeong-hee is still young enough to fight for love, and the world in which she lives gives her the courage to believe it might be possible.

The generation gap between herself and her mother, who it has to be remembered is only 38, cold not be more obvious. Suk-hee struggles against herself. She loves Sang-gyu, but the world tells her that it’s wrong and she must deny her feelings for the sake of social propriety. She can’t stand the way people look down on war widows, and she’s too afraid to give them any more ammunition. Given the relative mildness of the sanction on their relationship, in moral terms at least, it would be easy enough to read it as a metaphor for something else, especially with the repeatedly pregnant dialogue about the pain of not being permitted to marry the person that you love, that no one has the right to judge others for their personal lives, Sangyu’s sister’s aside about being “one of those people”, and finally Sang-gyu’s rather strange confession to Ok-ju that he “may have a personality disorder” in being unable to give up on his love for Suk-hee. It is definitely the case, however, that the gate that stands between them is a rigid an unforgiving society which denies love in fear of disrupting the social order.

Suk-hee feels guilty not only for her feelings, but feeling as if she’s getting in the way of Sang-gyu’s bright and rightful future. Meanwhile, no one seems to give much thought to poor Ok-ju, used as a pawn by all while pinning for Sang-gyu despite her conviction that he’s in love with someone else and will never truly be with her. Even Gi-cheol implies it’s her own fault not being “loving” enough, while she is left with nothing but sympathy for Suk-hee as another woman forever separated from Sang-gyu because of what other people think. This world is not, it seems, entirely ready for love. Suk-hee makes the “right” choice by many people’s reckoning, one filled with nobility and self sacrifice, yet it’s a choice that becomes increasingly impossible to accept and stands only in stark condemnation of the society which convinced her that misery was virtue.

Dongsimcho is the second of three films included in the Korean Film Archive’s Shin Sang-ok’s Melodramas from the 1950s box set. It is also available to stream via the Korean Film Archive’s YouTube Channel.

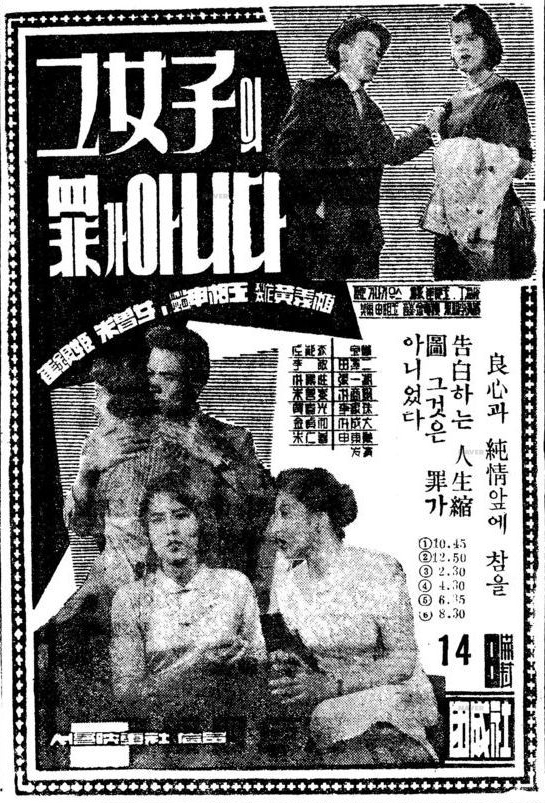

It’s Not Her Sin (그 여자의 죄가 아니다, Geu yeoja-ui joega anida) is, in contrast to its title, nowhere near as dark or salacious as the harsher end of female melodramas coming out of Hollywood in the 1950s. It’s not exactly clear to which of the central heroines the title refers, nor is it clear which “sin” it seeks to deny, but neither of the two women in question are “bad” even if they have each transgressed in some way. Drawing inspiration from the murkiness of a film noir world, Shin Sang-ok adapts the popular novel by Austrian author Gina Kaus by way of a previous French adaptation, Conflit. Shin sets his tale in contemporary Korea, caught in a moment of transition as the nation, still rebuilding after a prolonged period of war and instability, prepares to move onto the global stage while social attitudes are also in shift, but only up to a point.

It’s Not Her Sin (그 여자의 죄가 아니다, Geu yeoja-ui joega anida) is, in contrast to its title, nowhere near as dark or salacious as the harsher end of female melodramas coming out of Hollywood in the 1950s. It’s not exactly clear to which of the central heroines the title refers, nor is it clear which “sin” it seeks to deny, but neither of the two women in question are “bad” even if they have each transgressed in some way. Drawing inspiration from the murkiness of a film noir world, Shin Sang-ok adapts the popular novel by Austrian author Gina Kaus by way of a previous French adaptation, Conflit. Shin sets his tale in contemporary Korea, caught in a moment of transition as the nation, still rebuilding after a prolonged period of war and instability, prepares to move onto the global stage while social attitudes are also in shift, but only up to a point.