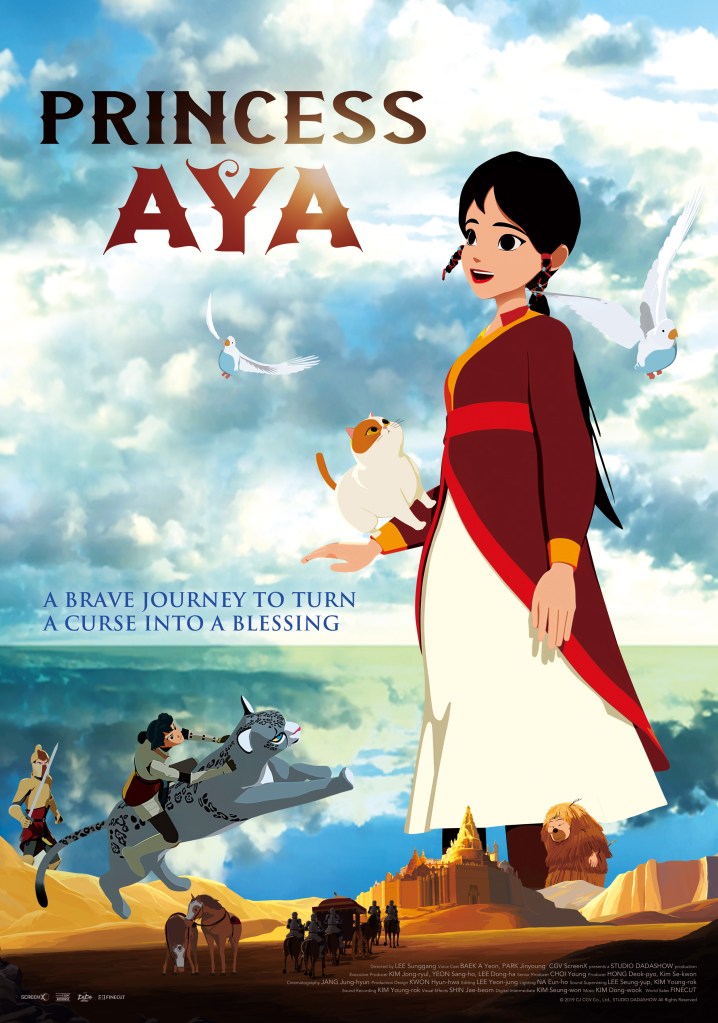

Animation made for children can often be a subversive affair, offering surprisingly progressive messages sometimes at odds with an otherwise conservative industry. Though quite obviously taking its cues from Frozen in terms of aesthetics and atmosphere despite its desert setting while drawing inspiration from classic fairytales, Princess Aya (프린세스 아야) is a sterling example, keen to sell the message that it’s OK to be different while emphasising that it’s prejudice and social exclusion which are the real enemy, creating only pain and resentment while those rejected by an intolerant society may eventually be consumed by their sense of betrayal.

Long ago in a feudal society, a strange curse begins to affect children born in the small kingdom of Yeonliji which causes them to turn into animals after coming into contact with animal blood. Some believe that the curse is the revenge of animals hunted for sport, while the cursed children are, ironically enough, abandoned to live as beasts in the forest or perish. The Queen, however, cannot bear to part with her child, Princess Aya (Baek A-yeon), and sacrifices some of her own life force in return for a magical bracelet from a tree god that will prevent the curse from manifesting. Years later, Aya grows up into a feisty teenage girl, while the kingdom is threatened by an oncoming incursion from desert nation Vartar who want its water. The Vartan prince, Bari (Park Jin-young), has proposed a dynastic marriage with one of Aya’s younger sisters to broker peace, but Aya has no intention of letting her sisters face such an uncertain fate and insists on going herself.

Of course, what she discovers, in true Korean period drama fashion, is that there’s intrigue in the court. Bari is not, as she feared, a hideous monster but a kind and handsome young man who is actively trying to prevent a war and protect Yeonliji (which is obviously what she wants too), but his treacherous uncle is ruling as a regent and secretly working against him. Meanwhile, attempts have been made on Aya’s life, and she’s lost the precious bracelet which allows her to keep her true nature hidden.

The curse appears to be a punishment manifested on mankind for its cruel treatment of animals, forcing Aya to feel the suffering of living creatures in pain and close to death. While Aya does her best to fight the darkness, another creature known as the “Beast” has allowed it to consume him, feeding on sorrow and determined to take revenge on the society which has abandoned and rejected him. It’s rejection that Aya too fears, as perhaps does everyone and most especially young women, but hers is a deeper seated anxiety in that she’s uncertain what will happen if her true nature is discovered.

Nevertheless, she moves towards an acceptance that her curse could also be a gift while beginning to believe that “no matter who I am I can be loved”. Yet she also feels a sense of guilt in using her amulet, knowing she is deceiving the prince, whom she’s come to admire, while fearing his reaction if she tells him the truth. Bari, meanwhile, is not so much hiding a secret as a lone figure of traditional nobility in a court filled with scheming intrigue. While his uncle plans to subjugate Yeonliji, Bari has been secretly drilling in the desert looking for water, admiring the flowers where they bloom even in adversity.

Bari refuses to make his men slaves of war, while Aya insists that they need to rebuild their society with a greater sense of compassion. She is afraid of her “difference” and her destiny, longing to be free but afraid of being seen. Eventually she realises that connection can be a strength and not a weakness as can authenticity and mutual understanding. She refuses to abandon the Beast as her society had done despite his wickedness, still hoping to save and bring him into her hopefully kinder world. Princess Aya shows kids that being “different” is nothing to be ashamed of, that no one is unloveable (even evil Beasts), and that the Princess is perfectly capable of saving herself but it’s no weakness to accept help when you need it or to give it when others are in need. A charming musical fairytale, Princess Aya wears its progressive values on its sleeve, always allowing its heroine to chart her own destiny while finding self-acceptance along the way.

Princess Aya screens in Amsterdam on March 7/8 as part of this year’s CinemAsia Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Review of Korean animation Kai (카이 : 거울 호수의 전설, Kai: Geowool Hosueui Jeonseol) first published by

Review of Korean animation Kai (카이 : 거울 호수의 전설, Kai: Geowool Hosueui Jeonseol) first published by