“Big city, small people, tough life” a jaded sex worker commiserates, slowly bonding with an illegal taxi driver trying to find a way to live in contemporary Kuala Lumpur. The ironically titled Hail, Driver! (Prebet Sapu) casts its cosmically unlucky hero adrift, literally roaming the city and coming in a sense to a new understanding of it thanks to his impromptu conversations with fares many of whom are only slightly more lucky than he is. Yet while his radio constantly updates him on the upcoming elections, he struggles to believe that real change is possible or that he will ever find a way out of his itinerant poverty.

Aman (Amerul Affendi) was once a writer, but times have changed and no one buys magazines anymore. He’s been living with his sister in the city, but his brother-in-law makes no secret of his unhappiness with the situation, arguing with his wife about Aman’s inability to contribute economically to the household. Hoping to make some extra cash, he decides to make use of his sole inheritance from his late father, a rundown but reliable and recently serviced vehicle, to become a driver with ride hailing app Toompang. The only problem is that Aman has no official driver’s licence and is unable to get one because of his colour blindness, while the car is technically not of a sufficient standard to be used as a taxi. Paying a middle man for fake documents, he begins working but is quickly made homeless when his brother-in-law changes the locks while he’s out one day and announces he’s bringing his own brother to live with him instead forcing Aman to make the car his home, using public conveniences to wash and occasionally sleeping in 24-hr establishments such as laundromats.

Aman’s plight is an encapsulation of the problems of the modern city, the radio explaining that house prices are a major point of interest in the upcoming elections. He searches for affordable accommodation but finds nothing suitable while quizzing his various fares about their living conditions, whether they rent or own their homes and how much they pay. One woman with a young son explains that of course she rents, there’s no way she could buy on her low salary while starting a business of her own is, she claims somewhat crassly, a no go because of the “flock of immigrants” in the city. Another of Aman’s fares reveals he came from Bangladesh some years ago, works in a hotel, and shares a reasonably priced apartment with his brother. Meanwhile Aman ferries sleazy politicians and their much younger mistresses to just such establishments.

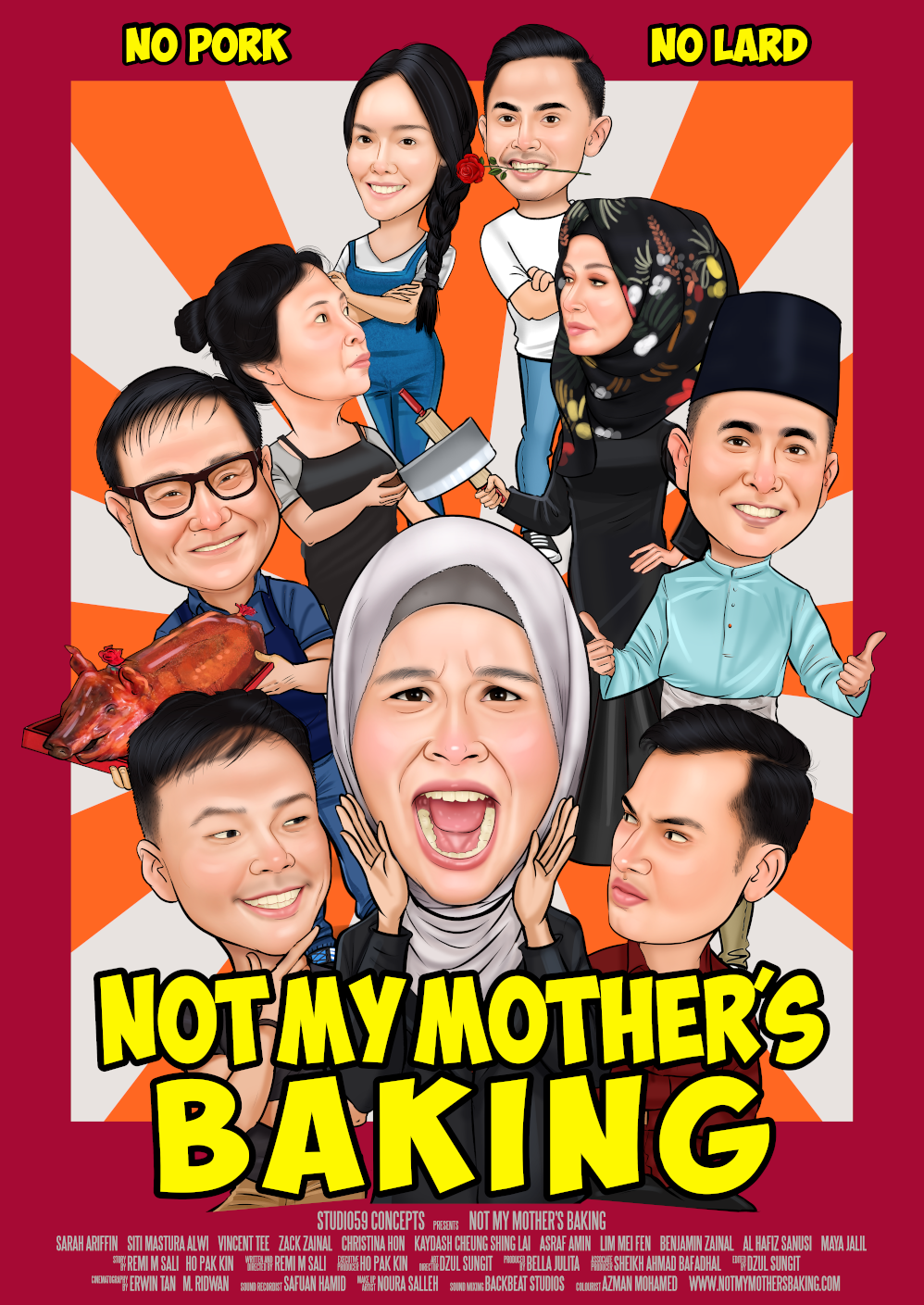

It’s his innate kindness, however, which eventually allows him to move forward after accidentally bonding with Chinese-Malaysian sex worker Bella (Lim Mei Fen) who came to the capital from Penang in search of a better future. She offers to let him use her spare room in return for his services getting to and from her clients, but even as they begin to develop a kind of mutual solidarity Bella confesses that she’s never felt a sense of belonging in the capital while her abandonment issues, her mother apparently living in the US after leaving her behind at five years old, have left her feeling spiritually homeless. “Not all dreams can be achieved” she advises Aman, each of them united in a sense of defeat as they reflect that nothing ever changes hearing the news that the party in power has again won the elections despite the ongoing problems in the city.

Filmed in a crisp black and white, reflecting both Aman’s colour blindness and sense of hopelessness, Hail, Driver! paints an unflattering portrait of life on the margins of a burgeoning metropolis but eventually finds a degree of possibility in the unexpected, perhaps in its way transgressive, connection between the Malay taxi driver and Chinese sex worker who eventually find a sense of belonging, of home, in each other even as they bond over shattered dreams and urban disappointment. A striking debut feature Muzzamer Rahman’s empathetic drama captures the elusive city in all its unobtainable beauty, apartment blocks literally towering oppressively over the kindhearted Aman, but finally suggests that freedom may lie only outside of its repressive borders.

Hail Driver! streamed as part of this year’s hybrid edition Udine Far East Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)