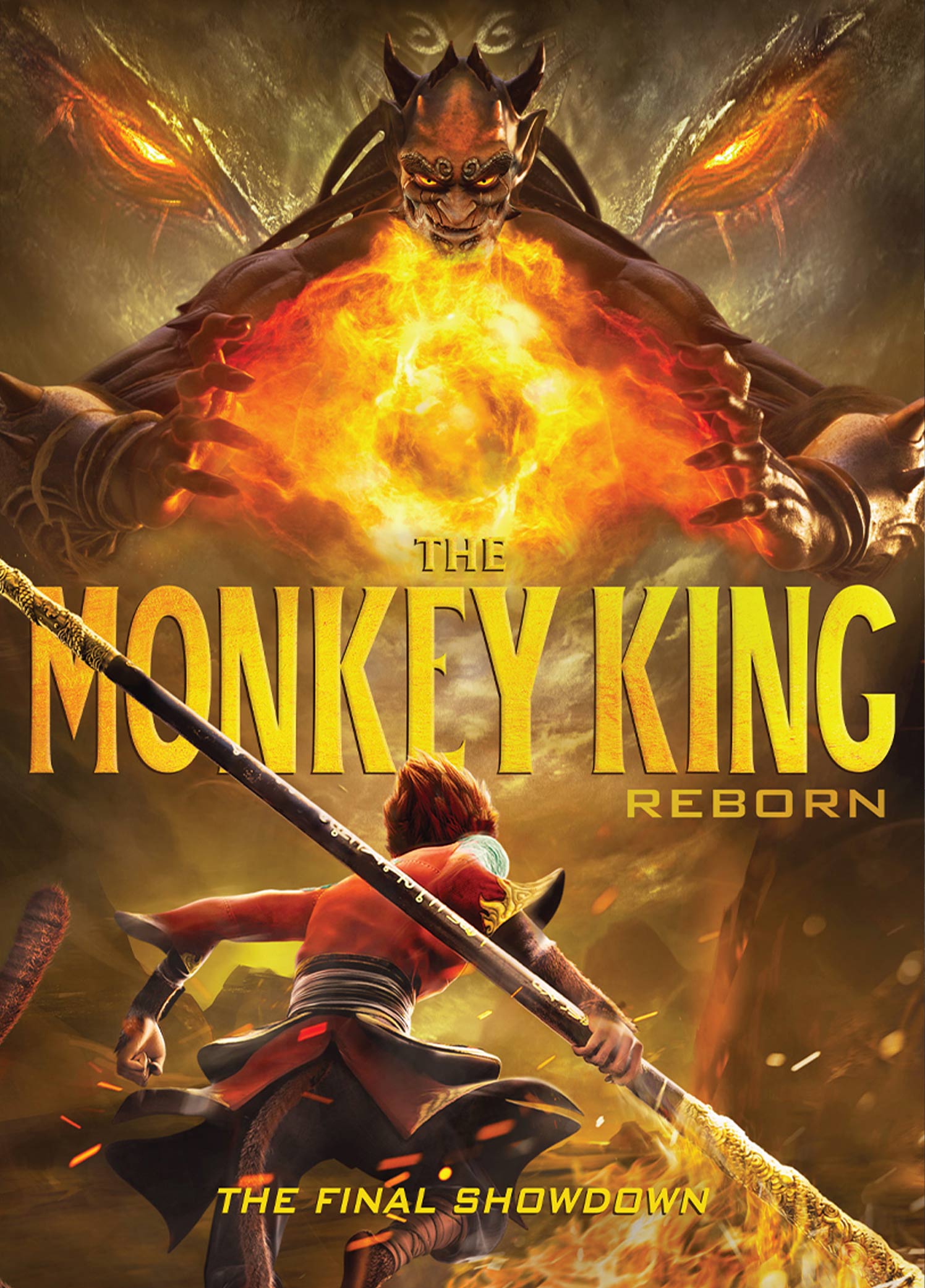

Sun Wukong comes to believe in his own soul while standing up to a cruel and oppressive reincarnated demon king intent on destroying the world in Wang Yun Fei’s anarchic family animation The Monkey King: Reborn (西游记之再世妖王, Xīyóujì zhī zài shì yāo Wáng). Reborn is in a sense also what Sun Wukong becomes in Wang’s defiantly egalitarian adventure which sees the regular crew from Journey to the West becoming temporary guardians to an adorable ball of anthropomorphised qi while The Great Sage Equal to Heaven contemplates what it is to be a “demon” and if he’s necessarily as “bad” or “evil” as some seem to believe him to be.

As usual, Wukong (Bian Jiang) is travelling with the monk Tang Sanzang (Su Shangqing) and fellow demons Bajie (Zhang He) and Wujing (Lin Qiang) heading to India to retrieve Buddhist scriptures to bring back to China. On the way, they stop off at a temple where Wukong and his friends end up causing a ruckus by eating some of the temple’s treasured manfruit from a tree which only produces 30 every 1000 years. 1000 years doesn’t seem so long to Wukong so he thinks little of it but is later caught out by two snooty monks, grows indignant, and gets into a fight with an immortal eventually destroying the tree in temper only to realise that he’s accidentally released Yuandi (Zhang Lei), the ancestor of all the demons sealed within the tree thousands of years previously by a Buddhist monk who sacrificed all of his qi to do so. Threatened with being re-imprisoned himself and determined to rescue Tang who has been kidnapped, Wukong has no choice but to stop Yuandi before he reassumes his full strength in around three days time.

Meanwhile, the trio is joined by a tiny manfruit-like ball of qi Wukong nicknames “Fruity” (Cai Haiting), originally reluctant to take him with them but advised that his qi is the best weapon against Yuandi. As the film opened, Wujing had been contemplating what it means to have a soul, Tang reassuring him that when he feels he has one it will be there. Following through on the egalitarian message, he later says something similar to Yuandi, certain that all sentient creatures are equal, but the moody Wukong remains sullen and resentful constantly insulted as an “evil” demon while internally convinced he can’t be anything else. Yet despite himself he takes on a paternal role while looking after Fruity who later explains to him that there are good demons and bad and that he has a kind soul.

Yuandi by contrast merely rolls his eyes when most of his demon minions are cut down, lamenting that they had become weak and the weak do not deserve to live. In the process of searching for his own soul, it’s this cruel and oppressive worldview that Wukong and the others must finally resist, protecting Fruity while battling the darkness with the confidence of self knowledge as their best weapon. Meanwhile, it’s clear that the Buddhist world is not exactly free of corruption either, the two snooty monks instantly looking down on Tang ironically because of his unostentatious attire uncertain why they’re expected to share their treasure with someone so seemingly undeserving. Then again, when they’re sent off to petition the Jade Emperor quite the reverse is true as they’re kept waiting outside while heaven’s border guard painstakingly fills out paperwork in only the best calligraphy while insisting each petition should be treated impartially no matter who it comes from even though the monks had quite clearly expected to jump the queue.

Selling a positive message of self-acceptance and universal equality The Monkey King: Reborn also boasts a series of thrilling and elegantly drawn action sequences as the trio face off against the forces of darkness, along with some zany humour and Wukong’s characteristically anarchic energy not to mention the unbelievably cute yet somehow profound Fruity who can’t bear all the senseless carnage and depletes himself to cure the innocent townspeople of their demonic corruption. In the end it’s not only Wukong who is reborn as he realises that nothing’s ever really gone forever, just altered in form, while it is possible to repair damage done with humility leveraging the power of self-acceptance against a dark and selfish desire for destruction.

The Monkey King: Reborn is released in the US on DVD & blu-ray Dec. 7 courtesy of Well Go USA in an edition which includes both the original Mandarin-language voice track with English subtitles and an English dub.

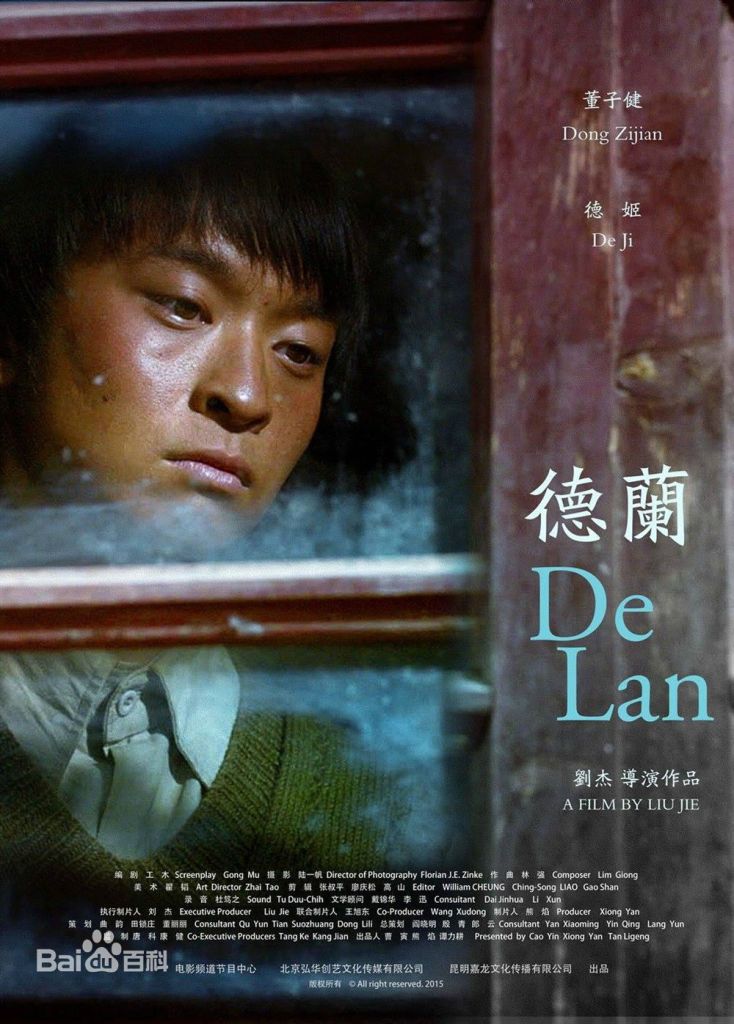

Set in 1984 in a rural Chinese backwater, De Lan (德蘭) is named not for its central character, but for his first love – a mountain woman far from home in search of a missing relative. Tasked with following De Lan (De Ji), Wang (Dong Zijian) finds himself entering a strange new world which he is incapable of fully understanding, not least because he doesn’t speak the language. A wordless love story between the tragic De Lan and the adolescent Wang is destined to end unhappily, but will affect both of them in quite profound ways.

Set in 1984 in a rural Chinese backwater, De Lan (德蘭) is named not for its central character, but for his first love – a mountain woman far from home in search of a missing relative. Tasked with following De Lan (De Ji), Wang (Dong Zijian) finds himself entering a strange new world which he is incapable of fully understanding, not least because he doesn’t speak the language. A wordless love story between the tragic De Lan and the adolescent Wang is destined to end unhappily, but will affect both of them in quite profound ways.