“We’ll stay in the mountains and never go back down,” embattled peasant Niu Er (Huang Bo) insists having safeguarded his Dutch cow through the Sino-Japanese war and onward towards the new China. A satire revolving around the senselessness of war and the endurance of Chinese everyman, Guan Hu’s Cow (斗牛, Dòu Niú) is also testament to the bond between man and beast who somehow manage to survive through the chaos and the carnage all around them.

That said, Niu Er was not originally happy about being forced to take care of the giant black and white cow he christens Jiu after his feisty wife (Yan Ni). He had a cow of his own. A nice little yellow one he thought was perfectly fine. He didn’t really see why his little yellow cow didn’t deserve the fancy grain reserved for Jiu and got into trouble for giving some of it to her. But when the entire village is wiped out by the Japanese with the cow the only other survivor, Niu Er thinks he has a duty to save it because the village was supposed to be keeping it safe for the 8th Army. It turns out it was an anti-fascist cow sent by the Dutch to feed wounded soldiers busy fighting the Japanese and the 8th Army are supposed to be coming back for it after they return from a strategic retreat.

But Niu Er’s problem is he’s not just in hiding from the Japanese because there’s also fighting going on between the nationalists and communists. Once bandits have killed all the Japanese who invaded Niu Er’s village, refugees soon turn up with their eyes on the cow. Because he’s a nice man, Niu Er shares some of the milk with a starving woman cradling a baby before realising there’s a whole crowd of other displaced people behind her. But as much as Niu Er gives them, they can’t be satisfied, and insist on over milking Jiu until she becomes ill with mastitis before one of them suggests killing and eating her instead. Not only is this quite shortsighted given that it will only feed them immediately whereas Jiu could still go on producing milk indefinitely if only they were a little less greedy, but it speaks to the loss of their humanity in the midst of their desperation. When Niu Er makes it clear he’s not on board with them killing his cow, the doctor leading the refugees pretends to help cure Jiu’s illness but is really trying to corner Niu Er so they can kill him and eat the cow anyway. In any case, they end up paying for their greed and cruelty by falling foul of all the booby traps the Japanese troops left behind.

To that extent, the Japanese aren’t all that bad. One of them, whom Niu Er finds hiding in a tunnel, used to be a dairy farmer and shows Niu Er how to treat Jiu’s illness which is why Niu Er decides to save him and take him with them to their place of salvation in a cave in the mountains. But a nationalist is already hiding there and the pair end up killing each other. The film seems to ram the point home that there was no real difference between these men who had no particular reason to fight when Niu Er ends up burying them together in a makeshift grave. Setting himself apart from all this war and absurdity, he resolves to stay above it by living in the mountains with Jiu and planting new grain up there for them both to live on.

Seven years later when the PLA eventually turn up, they’ve forgotten all about the cow and are keen to tell Niu Er that they don’t take things off peasants so the cow is now lawfully his. The soldier may be a representative of the new Communist and caring China, but it otherwise seems that Niu Er has been become a guardian of the China that existed before the Japanese with the petty goings of his random village in a way idyllic and filled with nostalgia. Yet it had its problems too. The village chief seems to have had a xenophobe streak, restricting milk from those not born in the village like the widow Jiu who became Niu Er’s wife. She is in many ways an envoy of an idealised communist future in her feminist attitudes and feistiness even amid the sexist and traditionalist culture of the village. Nevertheless, Niu Er and Jiu the cow seem to have found a little alcove of serenity up the mountains of the real China free from the chaos below.

Trailer (Simplified Chinese / English subtitles)

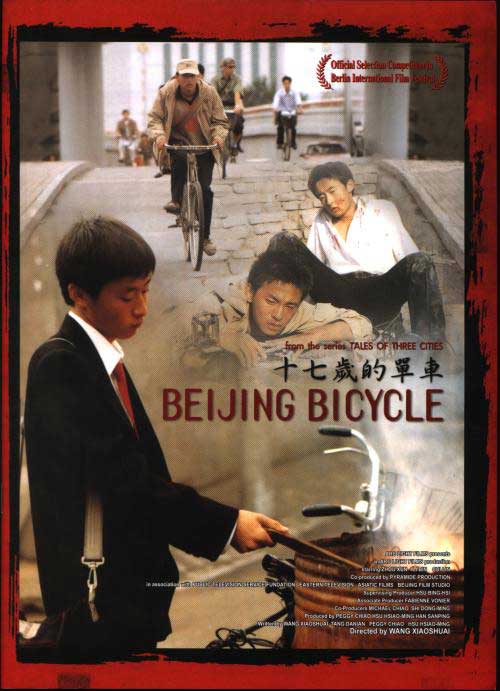

There are nine million bicycles in Beijing (going by the obviously very accurate source of a chart topping song) but there are 11.5 million inhabitants so that’s at least two million people who do not own a bike. Still, if you’re in the unlucky position of having your bike stolen by one of the aforementioned two million, your chances of finding it again are slim. Luckily for the protagonist of Wang Xiaoshuai’s Beijing Bicycle (十七岁的单车, Shí Qī Suì de Dānchē), he manages to track his down through sheer perseverance though even once he gets hold of it again his troubles are far from over.

There are nine million bicycles in Beijing (going by the obviously very accurate source of a chart topping song) but there are 11.5 million inhabitants so that’s at least two million people who do not own a bike. Still, if you’re in the unlucky position of having your bike stolen by one of the aforementioned two million, your chances of finding it again are slim. Luckily for the protagonist of Wang Xiaoshuai’s Beijing Bicycle (十七岁的单车, Shí Qī Suì de Dānchē), he manages to track his down through sheer perseverance though even once he gets hold of it again his troubles are far from over.