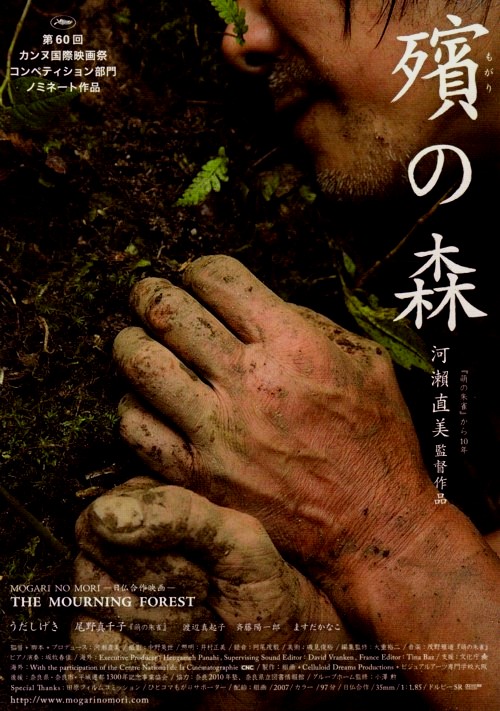

“There are no set rules,” according to the reassuringly steadfast head of a rural nursing home in Naomi Kawase’s The Mourning Forest (殯の森, Mogari no Mori). Uttering the phrase several times in many different contexts, the words prove truer than they first seem, eventually reassuring the grief-stricken heroine that there is no right way to feel or correct way to mourn, simply a gentle process of accommodation. An unexpected Palme d’Or winner, Kawase’s fourth feature sees her shifting into a more familiar arthouse register yet maintaining her trademark style as two lost souls, one old and one young, search for the “end of mourning” in the beauty of nature.

The young one, Machiko (Machiko Ono), is a recently bereaved mother who has just taken a job at a local nursing home. We never find out exactly how her son died, in fact we only infer he did from the photo and incense on Machiko’s makeshift altar, but a later conversation with her presumed husband encourages us to assume that she blames herself for his death. Consequently, she perhaps recognises something in the dead-eyed vacancy of one of the home’s residents, Shigeki (Shigeki Uda), who crosses out the middle character, meaning 1000, in her name to make it read the same as his late wife Mako’s. Mako (Kanako Masuda) died 33 years previously, which according to the Buddhist priest visiting the facility means that her spirit will soon be leaving this plane for good, transitioning to the other world to become a Buddha.

Something in Shigeki, whose name literally means “stimulation” though it is in fact the actor’s own, is awakened by the priest’s pronouncement, encouraging him to embark on a long-delayed journey. The priest too had been responsible for the initial connection between the two grieving souls, giving a perhaps insensitive lecture on the difference between living and existing which lies apparently in the ability to feel alive, something which neither of them perhaps do. For unclear reasons, Machiko agrees to travel with Shigeki to look for his wife’s grave, deep in the forest. Unfortunately they get into an accident on the way and while Machiko goes to look for help, Shigeki wanders off with the consequence that the pair of them eventually end up lost in the woods.

“I was lost but now I’m here,” Shigeki finally explains, fighting his way through what was assumed to be dementia in his quest to say goodbye to his late wife for good before her soul leaves this world. The pair traverse somewhat difficult terrain, culminating in a painful episode in which Machiko begs the older man not to cross a wild river as if he were determined to cross the styx, or then again perhaps there is another explanation for the rawness of her distress. “We’re alive” they exclaim as they warm themselves by an elemental fire, settling the priest’s question once and for all as they press on in search of a grave and each of making peace with the past.

As Wakako (Makiko Watanabe) had said, there are no set rules for mourning. Shigeki lived with his grief for 33 years and only found the courage to face it in the knowledge that there was no more time. Yet he reassures Machiko that “the water of the river which flows constantly never returns to its source”. In travelling with Shigeki, Machiko too begins to reckon with her grief, finding a kind of release in his catharsis and witnessing the proof of his long years of devotion suddenly given new purpose. She too is able to lay her mourning to rest in the natural beauty of the verdant forest.

Beautifully capturing the majesty of nature, Kawase shifts away from her trademark style swapping anarchic handheld for stateliness in the stillness of Machiko’s grief while quietly observing the ordinariness of the nursing home even as one resident relates her own grief in having lost a child. Filled with a deep sadness in its melancholy meditation on love, death, loss, and grief, The Mourning Forest is nevertheless a strangely uplifting, elegiac experience in which an old man and young woman find strength in their shared connection as they journey together towards the end of mourning and, perhaps, a rebirth in making at least a kind of peace with their grief and their longing.

Original trailer (English subtitles)