The truth is, most people genuinely mean well but they often make mistakes. They make them because they don’t think things through, fail to consider perspectives outside of their own, or act on assumptions that they later realise were incorrect (or tragically do not). Most people will come to understand where they went wrong and resolve to do better in future, but you don’t always get a second chance and a momentary lapse in judgement can do untold and sometimes irreparable harm.

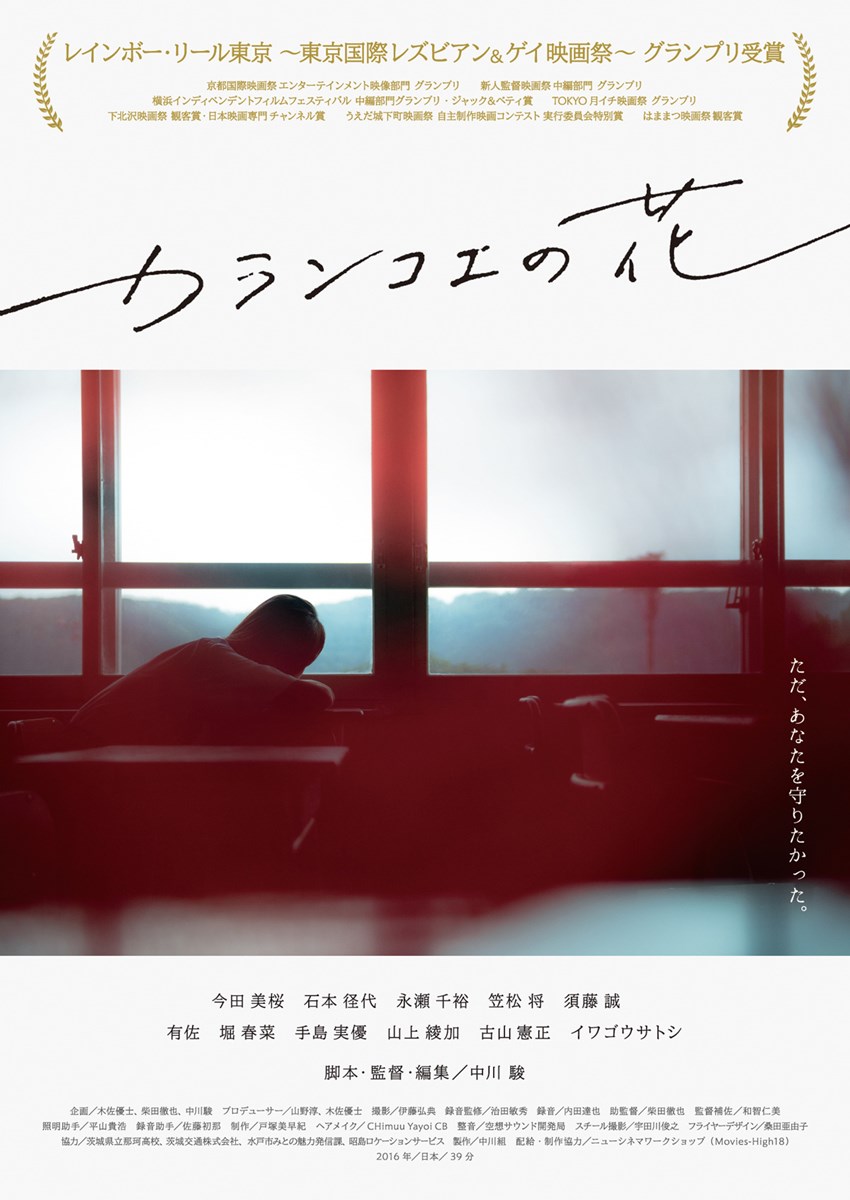

Perhaps that’s just a lesson you learn as a part of growing up, but it doesn’t make it any less painful or indeed shocking at least for the heroine of Shun Nakagawa’s 40-minute mid-length film Kalanchoe (カランコエの花, Kalanchoe no Hana). The film’s title refers to a bright red plant that in the language of flowers means “I will protect you.” But protection can be a double-edged sword, and Tsuki’s (Mio Imada) later attempt to do just that for her friend seriously backfires well meaning though it may have been. The same is true of an ill thought out decision by the school nurse to give a mini lecture on LGBTQ+ issues to Tsuki’s class when their English teacher’s off sick. Because it was only their class that received this talk, some of the students assume it must mean that one of them is gay and begin a kind of witch-hunt trying to figure out who it might be which is completely the opposite of the reaction the talk was supposed to provoke.

Of course, the nurse meant well but it probably should have occurred to her to make sure the class wasn’t singled out and support was available for any students who might be experiencing anxiety surrounding their sexuality or gender identity rather than doing something essentially superficial to make herself feel better. Though most of the students are indifferent to the talk, the class clown bears out the latent homophobia of the current society in badgering the nurse to find out if there are any gay people “or other creeps” in their class while vowing to root them out and making it a kind of game to catch one. The girls, meanwhile, engage in some aggressive heteronormativity talking about boys and pretty much making it impossible for any of them to declare themselves for whatever reason uninterested.

As it turns out, one student overheard the conversation in the nurse’s office that provoked the talk and knows that one of the students is indeed gay, perhaps inappropriately telling Tsuki who it is in an effort to relieve the burden on herself of carrying this explosive information. When Sakura (Arisa), the student in question, begins to tell Tsuki that she’s gay, Tsuki firstly reacts well patiently waiting rather than admit she already knows though in the end Sakura cannot go through with it despite having said that Tsuki was the person she most wanted to understand. Sakura had admired Tsuki’s red scrunchie that she herself had worried was too bold, prompting her to turn over in her hands and consider it as if thinking over how she intends to react to this information and how she herself may or may not feel.

But on her second opportunity she missteps. Fearing Sakura has been outed, she loudly and clearly says it isn’t true even though she knows it is in a mistaken attempt at “protection” as if she were clearing her name which is also an expression of her own latent belief that it being true is in someway bad. In its way, it echoes the fateful moment in William Wyler’s The Children’s Hour in which Shirley MacLaine tells Audrey Hepburn there’s some truth in the rumour, but Audrey Hepburn tells her she’s lost her mind and though the outcome may not be quite as devastating it’s still a crushing blow with the brutal conclusion implying nothing more than Tsuki will have to live with her bad decision and the pain it caused for the rest of her life. Nakagawa skips between idyllic scenes of the girls on a bike, head gently resting on a shoulder, and scenes of regular high school life but ends on a note of quiet tragedy that feels somehow casually cruel.

Kalanchoe is available to stream via SAKKA from 20th September.