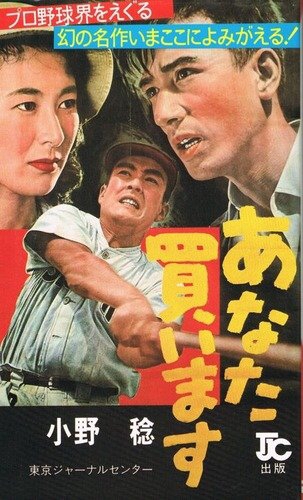

In I will Buy You (あなた買います, Anata Kaimasu, a provocative title if there ever was one), Kobayashi may have moved away from directly referencing the war but he’s still far from happy with the state of his nation. Taking what should be a light hearted topic of a much loved sport which is assumed to bring joy and happiness to a hard working nation, I Will Buy You exposes the veniality not only of the baseball industry but by implication the society as a whole.

In I will Buy You (あなた買います, Anata Kaimasu, a provocative title if there ever was one), Kobayashi may have moved away from directly referencing the war but he’s still far from happy with the state of his nation. Taking what should be a light hearted topic of a much loved sport which is assumed to bring joy and happiness to a hard working nation, I Will Buy You exposes the veniality not only of the baseball industry but by implication the society as a whole.

Kishimoto works as a scout for a popular Tokyo baseball team. His job is to find the promising young players and charm them into accepting a contract before any of the other teams get to them. His first assignment doesn’t go well when he arrives at an ace pitcher’s home only to be told the subject in question is recovering from having lost a finger in a workplace accident. No major league career for him – Kishimoto heads home without even introducing himself. The next prospect is very exciting – a semi-well known college ball player who might be persuaded to turn pro. However, the student, Kurita, is “managed” by a benefactor, Kyuki (whose name literally means “ball spirit” in Japanese) who seems to be a difficult man to deal with. Nevertheless, Kishimoto is young, ambitious and determined to get Kurita on side by any means possible.

It’s just baseball, one might think but it’s almost as if we’re playing for souls. Everyone is lying, everyone is double crossing everybody else and everyone has their own interests at heart all the while swearing they only want the best for Kurita. Kurita has become a trophy, no one has even thought to ask him if he actually wants to keep playing baseball. He’s no no longer a person for them so much as a flag to be captured. This might actually work out quite well for Kurita himself who, it turns out, is far from the country bumpkin everyone has him pegged as. Though surrounded by carping relatives who are also all intent on exploiting his talent, the possibility of Kurita suddenly discovering the power to make his own decisions is a threat to everyone that they haven’t even considered yet.

Kyuki himself is the bad guy we’ve all been set up to be suspicious of but may actually turn out to be the most decent hustler in the picture. They say he spied for the Chinese during the war but is it a rumour you can really believe or just the jealous slurs of his various rivals? He himself says he taught Chinese girls to use the bayonet and carries an air of aloofness that makes him seem untrustworthy. He’s bankrolled Kurita’s education and taken on the position of a father to him over the last four years but how much of that is genuine feeling and how much financial investment? Kyuki is a married father with a family out of town but is sort of living with the older sister of Kurita’s girlfriend which is an awkward situation in itself. He also claims to have a serious gallstone problem which requires an operation though others claim he’s putting it on. Who is Kyuki, with his suspiciously apt name and hard nosed attitude can we trust him, or not?

I Will Buy You is a characteristically angry and cynical effort from Kobayashi and though it’s still a fairly early work carries some of his later technical prowess. Stripping the mask away from what is assumed to be a gentle pastime, the film lays bare the money hungry desperation of post-war Japan. Money ruins everything, even something as innocent as baseball. The Kurita from the end of the film is not the idealistic young student who came to Tokyo but a canny self-interested individual. Whether or not this transformation, and the accompanying transformation of Kishimoto whose eyes have been well and truly opened, is for the better or not maybe a matter of personal perspective but it’s not hard to guess where Kobayashi stands.

I Will Buy You is the second of four early films from Masaki Kobayashi available in Criterion’s Eclipse Series 38: Masaki Kobayashi Against the System DVD boxset.