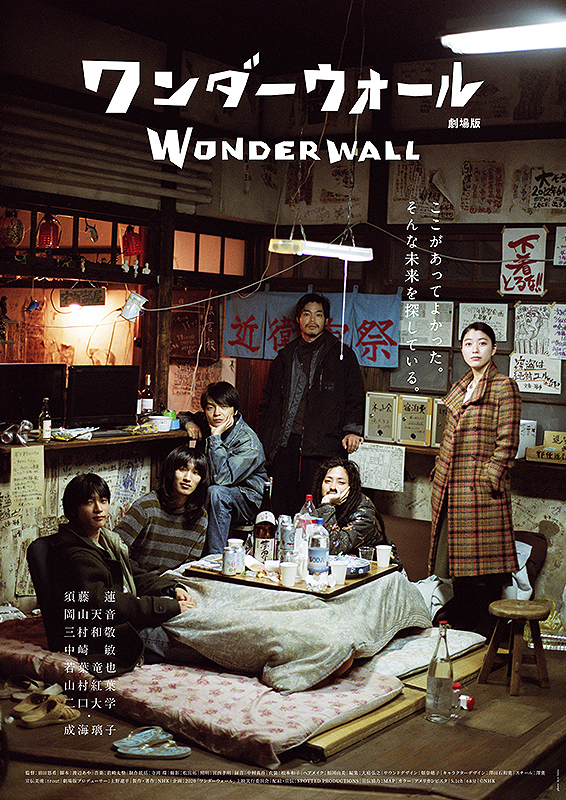

It’s funny, in a way, that young people are often the ones fighting to preserve the old while those in middle-age and beyond are largely keen to bulldoze the past for future gain. Yuki Maeda’s campus drama Wonderwall (ワンダーウォール 劇場版, Wonderwall: Gekijoban) sees a collection of students take a stand against the bureaucratic capitalism of their university in their attempt to save a much loved dorm but largely finding their efforts frustrated by an implacable hierarchy.

The Konoe Dorm at Kyoto University was built in 1913, which is to say the beginning of the Taisho era in which arts and culture flourished in a rapidly modernising and international nation. As one of the students tells us, Konoe is run not by the faculty but the students themselves and operates like a commune in which there is no hierarchy, all are equal and equally responsible. They have regular “meetings” about various domestic problems such as refuse collection which can go on for hours because all decisions must be unanimous while they also operate gender neutral bathrooms so that everyone really can be equal and free to be themselves. It’s impossible not to see the university’s attempts to destroy it as an attempt on the students’ autonomy and an attempt to impose order on their bohemian existence.

At more than one point, a student remembers walking past the alley that leads to the dorm in the dark and seeing the light glowing from its doors as if beckoning them in. In this space, the students inherit what has been passed down to them while teaching each other and the next generation what they know including the negotiation skills they’ve been using to argue their case in their ongoing battle with the faculty. The film’s title refers to a plastic screen that was placed in the student affairs office separating the students from the staff so that they could no longer meet them on their own terms. The narrator likens the wall to the one that fell in Berlin in 1989 and laments that back then we knocked walls down but now we only throw them up. The students argue that the dorm is well built and of architectural interest while it would otherwise be possible to renovate and bring it up to current earthquake codes if only the university would agree. Tragically, a sympathetic teacher who is forced to agree with them is then compelled to reverse his decision and shockingly dies not long after presumably from the stress of the situation along with his own inner conflict regarding the treatment of the students.

Mifune (Satoshi Nakazaki), the leader of the protests, eventually becomes disheartened. They managed to oust the old battleaxe from the front desk and assumed they could take a step forward to the next boss, but she was merely replaced and by a pretty young woman to boot leaving the guys feeling like they’ll never win. It transpires that the university wants the land the dorm sits on to build a high rise along with additional medical and engineering labs as these are the subjects that bring in funding which is otherwise thin on the ground from the current government. Yet as a visitor says, if prosperity made you happy there wouldn’t be so many young people who feel they have no option other than to take their own lives. If so many people are fighting for its survival, the dorm must have something essential for human happiness. Mifune comes to describe his feeling for the building as something like love in the warmth with which it inspires him.

Quite poignantly, Maeda ends on a series of title cards revealing that the university now refuses to speak to the student body at all and has in fact silenced them, even going so far as to sue 15 tenants who refused the order to move out. Another of the students wonders if the dorm was a victim of its own success, that their “utopian” thinking left them unable to unite for a common goal and perhaps it would have been better if they’d turned to the dark side and gone in all guns blazing in a show of violent defiance. The action shifts to a pair of musical set pieces in which the students and well-wishers play the “Wonderwall” song as a makeshift orchestra breathing life into the rapidly dilapidating building’s walls while continuing to fight for the survival not only of the Konoe Dorm but everything it represents in the freedom and community the students fear will soon disappear from the their lives.

Original trailer (English subtitles)