We don’t move forward in this dance, comments the lady currently being waltzed by a charming lost soul. Don’t worry, he says, that’s not a bad thing. Indeed, Out There, the first independent feature film from director Takehiro Ito exists in a fixed yet liminal space, here and not there as its protagonist finds himself without the proper place to be. Conceived as a way of salvaging some of the material collated for a documentary on the late Taiwanese director Edward Yang, Out There takes more of its cues from Tsai Ming-liang or even Lav Diaz in its preoccupation with the intersection between time, existence, and place. If that all sounds to weighty, there’s a little whimsy in here too, but the intent is a serious one as nationhood (or the lack of it), drifting cultures, love and history all conspire to confuse and distract the course of a young man in search of an identity which is entirely his own.

We don’t move forward in this dance, comments the lady currently being waltzed by a charming lost soul. Don’t worry, he says, that’s not a bad thing. Indeed, Out There, the first independent feature film from director Takehiro Ito exists in a fixed yet liminal space, here and not there as its protagonist finds himself without the proper place to be. Conceived as a way of salvaging some of the material collated for a documentary on the late Taiwanese director Edward Yang, Out There takes more of its cues from Tsai Ming-liang or even Lav Diaz in its preoccupation with the intersection between time, existence, and place. If that all sounds to weighty, there’s a little whimsy in here too, but the intent is a serious one as nationhood (or the lack of it), drifting cultures, love and history all conspire to confuse and distract the course of a young man in search of an identity which is entirely his own.

Beginning with an interview or perhaps an audition, the onscreen director questions the man who will be our star, Ma, about his motivations for applying – only, characteristically, he doesn’t quite know. From what he tells us, it seems his interests are largely introspective, unable to find a place to exist, perhaps he can carve one out for himself inside the fictional world of a film. Ito returns to this interview (or series of interviews?) throughout the action as Ma shows an apt desire to dissect himself on camera. The director is a minor player as Ma takes over, but like Ito he is trying to recover something from the ashes of a lost project, his producer sitting to the side, neatly picking apart the director’s somewhat thin proposal for a film about a cross cultural couple in which “everything happens by chance”.

The historical relationship between Tokyo and Taipei is perhaps a complicated one (though significantly less complicated than with many of its other neighbours), but there is a third party in this difficult romance in the spectre of America. Returning to Taiwan in the second segment, notably titled Land of Shadows, Ma talks to his parents about their views on global culture as Green Card holding Taiwanese who never made the move. In his original interview, Ma explained that one of the reasons he came to Japan was that he always felt like an outsider in Taiwan, unable to express himself fully. Having spent some time in the US as a child, Ma has a feeling America is “not for him”, but has also found that Japan is probably not the place he’s supposed to be either, and unlike his family he does not feel as if he can simply live out his days in his native Taiwan.

In a final discussion with Ayako – the actress in the film which never quite happens (in a sense, outside of the way it’s happening for us), Ma talks about the importance of memory which prompts Ayako to remark that it’s as if everything is already in the past for him. As if to symbolise Ma’s lack of forward progress, everything which happens in Tokyo bar a single flash of colour at the end of the interview sequence is cast in sharp black and white. Taiwan, by contrast, is shot in verdant colour though allowing for 16mm and 4:3 framing adding to the sense of nostalgia and homesickness which seem to invade Ma’s mind. This Taiwan is a place of backstreets and ruins, faded grandeur and unseen histories. Empty cinemas and abandoned film eventually give up their ghosts, but it’s Ma himself who seems to join them as he fades into the frame, here and not here as he repeatedly doubts the matter of his own existence.

There’s a slight irony in the way America has been idealised as a place of possibility given its (until extremely recently) severing of diplomatic ties with the island nation of Taiwan. Seeking a home in a place which refuses to acknowledge the land in which you were born exists may make one feel like a ghost, but Ma’s sense of existential dislocation runs deeper. A kind of hiraeth, a longing for a home which doesn’t quite exist, becomes a force which propels and halts in equal measure. Skating around Tokyo on his roller blades, Ma has no particular destination in mind except perhaps to escape himself. He takes photos of places because he doesn’t want to point his camera at people, refusing human connections which will have to be broken in his ongoing quest for a sense of belonging. As the director puts it, there are many endings but as long as he remains fixed on the concept of “there”, Ma risks losing the idea of “here” which remains in a state of perpetual future past, outside of this liminal space in which nothing moves or changes.

Ito’s drifting, experimental approach moving between documentary, narrative and fantasy with the borders between each as unclear as the hero’s sense of identity is one which defies categorisation, as much about the idea of place as the characterisation of the two cities at hand and the ever unseen spectre of the hovering America. Poetic, wistful, and imbued with a sense of loss, Out There is a poignant exploration of cultural dysphoria and existential confusion in an ever widening world in which past, present and future become indistinct in an endless journey onward to place or no place at all.

Currently available to stream worldwide via Festival Scope in connection with the International Film Festival Rotterdam.

Short scene from the end of the film:

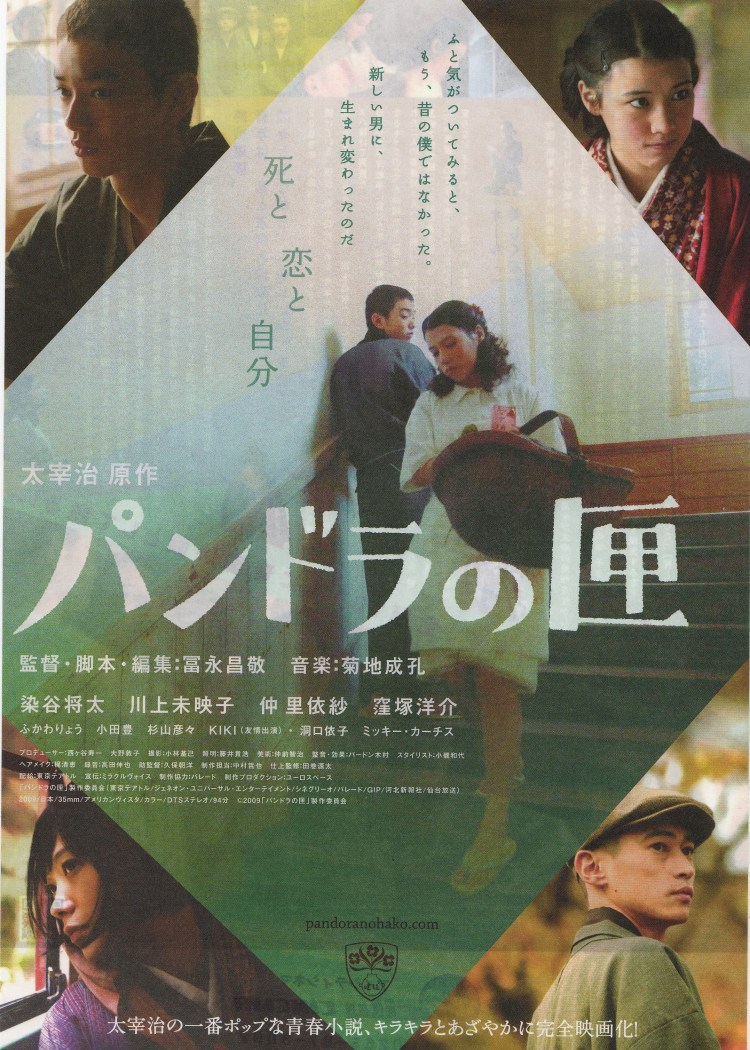

Osamu Dazai is one of the twentieth century’s literary giants. Beginning his career as a student before the war, Dazai found himself at a loss after the suicide of his idol Ryunosuke Akutagawa and descended into a spiral of hedonistic depression that was to mark the rest of his life culminating in his eventual drowning alongside his mistress Tomie in a shallow river in 1948. 2009 marked the centenary of his birth and so there were the usual tributes including a series of films inspired by his works. In this respect, Pandora’s Box (パンドラの匣, Pandora no Hako) is a slightly odd choice as it ranks among his minor, lesser known pieces but it is certainly much more upbeat than the nihilistic Fallen Angel or the fatalistic

Osamu Dazai is one of the twentieth century’s literary giants. Beginning his career as a student before the war, Dazai found himself at a loss after the suicide of his idol Ryunosuke Akutagawa and descended into a spiral of hedonistic depression that was to mark the rest of his life culminating in his eventual drowning alongside his mistress Tomie in a shallow river in 1948. 2009 marked the centenary of his birth and so there were the usual tributes including a series of films inspired by his works. In this respect, Pandora’s Box (パンドラの匣, Pandora no Hako) is a slightly odd choice as it ranks among his minor, lesser known pieces but it is certainly much more upbeat than the nihilistic Fallen Angel or the fatalistic