Fren (Prapamonton Eiamchan) has been having trouble sleeping. The doctor she visits to confirm her pregnancy tells her that she’ll have to stop taking her sleeping tablets, but to try gentle exercise such as walking on a treadmill instead. But Fren’s whole life is walking on a treadmill. The reason that she can’t sleep is that she works in HR for a terrible company and is knowingly bringing people into this world of cruelty and exploitation. She doesn’t really want to do the same for her baby, which is one reason she hasn’t told her husband Thame (Paopetch Charoensook) about the pregnancy even though they’ve been trying for two years.

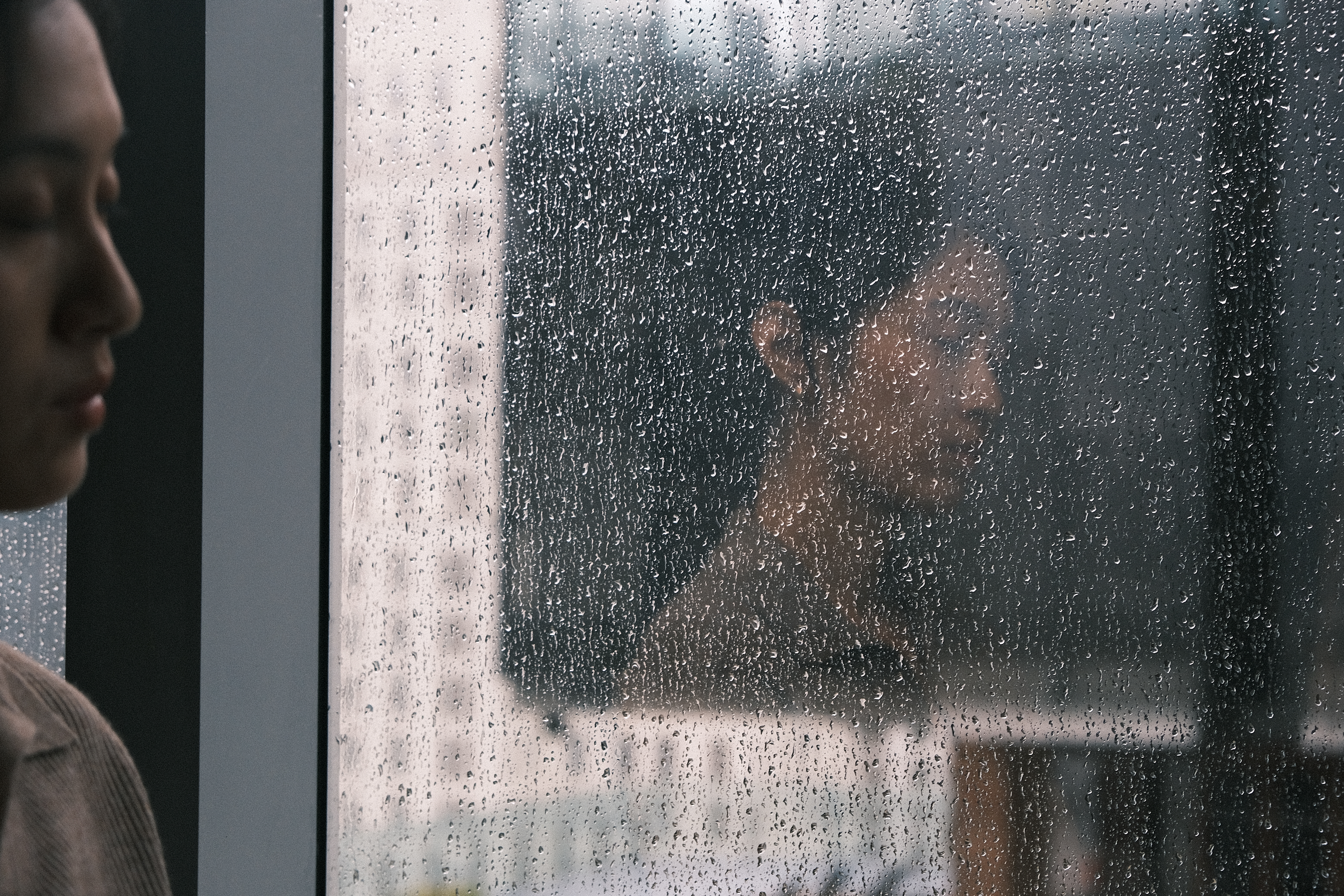

Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit’s Human Resources paints a fairly bleak picture of contemporary Thailand which is all the more chilling for its seeming normality. Fren listens to radio hosts talk about how the economy is tanking, there are floods in the north and no one’s doing anything about it, and also apples might be full of microplastics. You should also fit a filter in your shower because there’s cadmium in the water despite the government’s assurances that it’s safe. No wonder everyone feels on edge. Fren is increasingly uncomfortable with her own complicity, but sees no real way around it.

The main problem is that she works for a bully for who demands an apology from her when she has to have a word with him about his workplace behaviour which includes throwing piles of paper in the face of employees. June hasn’t been coming to work, and according to Fren’s colleague Tenn (Chanakan Rattana-Udom), a few other employees quit their jobs like this too because they just couldn’t live this way any more. Between Jak’s rages, low wages, and the demand to work six days a week, they know they can’t keep staff and feel bad about trying to recruit people. Tenn laments that given the economy, someone will desperate enough to bite, while the pair of them make themselves feel better by deciding to be upfront in interviews about the working culture and letting the candidates decide for themselves.

But how much do you really get to decide? When Thame finds out about the pregnancy, the couple to go look around an expensive international school. Fren agrees that’s very nice and the children seem happy, but it wasn’t their choice to be here and no one’s ever asked them if their parents’ idea of a “decent” person is what they really want to be. To Fren, the international school seems like another level of complicity in perpetuating the inequality in society that’s fuelling the violence and resentment all around them. The candidates might not have the option of turning down these jobs, and Fren doesn’t really have the option to leave, either. But Tenn comes from money and he could always get a job at his family’s company, so in the end only he has the choice of whether to stay or go.

Lectures Fren attends talk about the working revolution and the threat of AI, insisting that the “average” worker is dead because those jobs are gone, so the only way to make a mark is to work yourself to death and make use of personal connections. That seems to be the route Thame is taking after becoming chummy with the police chief in the hope of selling him some of their ultra thin stab vests that are comfortable to wear all day long as if implying the world has already got to that point that you need to be wearing armour at all times. He has a worryingly authoritarian streak and is incensed by the moped drivers who keep going the wrong way up their one-way street. Thame refuses to back up and let them pass, though isn’t so brave when one of them jumps off his bike and begins pounding the windscreen with his helmet. Humiliated by his inability to combat this kind of violence despite having brought it on himself, Thame later runs the guy over deliberately and then gets the police chief to make it go away.

Meanwhile, Fren feels as if all she can do is carry on walking the treadmill. The shutter at the car wash comes to symbolise that of the furnace at the crematorium where a colleague who took their own life because of overwork and bullying was laid to rest as if Fren’s life were a kind of living death. A famous woman convicted of a crime reveals she’s had an abortion because she didn’t want her son to be born in prison or to bring a child into that world. Fren isn’t sure she wants to either, but like everything else, she might not have much choice.

Human Resource screens as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)