In a time of crisis, the populace looks to the government to take action and save the innocent from danger. A government, however, is often forced to consider the problem from a different angle – not simply saving lives but how their success or failure, decision-making process, and ability to handle the situation will be viewed by the electorate the next time they are asked who best deserves their faith and respect. Pandora (판도라) arrives at a time of particularly strained relations between the state and its people during which faith in the ruling elite is at an all time low following a tragic disaster badly mishandled and seemingly aided by the government’s failure to ensure public safety. Faced with an encroaching nuclear disaster to which their own failure to heed the warnings has played no small part, Pandora’s officials are left in a difficult position tasked with the dilemma of sacrificing a small town to save a nation or accepting their responsibility to their citizens as named individuals. Unsurprisingly, they are far from united in their final decision.

In a time of crisis, the populace looks to the government to take action and save the innocent from danger. A government, however, is often forced to consider the problem from a different angle – not simply saving lives but how their success or failure, decision-making process, and ability to handle the situation will be viewed by the electorate the next time they are asked who best deserves their faith and respect. Pandora (판도라) arrives at a time of particularly strained relations between the state and its people during which faith in the ruling elite is at an all time low following a tragic disaster badly mishandled and seemingly aided by the government’s failure to ensure public safety. Faced with an encroaching nuclear disaster to which their own failure to heed the warnings has played no small part, Pandora’s officials are left in a difficult position tasked with the dilemma of sacrificing a small town to save a nation or accepting their responsibility to their citizens as named individuals. Unsurprisingly, they are far from united in their final decision.

As the film opens, a group of children marvel at the towers of the new nuclear plant which has just been completed in their previously run down rural town. Not quite understanding what the plant is, they repeat snippets they’ve heard in their parents’ conversations – that the plant is a “rice cooker” that’s going to make them all rich, or it’s a “Pandora’s box” which may unleash untold horrors. Still, they seem excited about this new and futuristic arrival in their dull little village.

Flashforward fifteen years or so and one way or another all the kids now work at the plant, like it or not, because there are no other jobs available. Kang Jae-hyuk (Kim Nam-Gil) is one such conflicted soul who doesn’t disapprove of the plant in itself but has good reason to fear that the powers that be are not taking good enough care seeing that both his father and older brother were killed during a previous incident at the plant some years previously. Jae-hyuk lives with his widowed mother (Kim Young-ae), sister-in-law (Moon Jeong-Hee), and nephew (Bae Gang-Yoo) but is reluctant to marry his long-term girlfriend Yeon-ju (Kim Joo-Hyun) due to his lack of financial stability and growing disillusionment with small town life.

Meanwhile, the wife of the Korean president has been passed a file by a whistle-blower hoping to bypass the corrupt bureaucracy and go directly to the top. The file, compiled by a worried engineer, details all of the many failings at the recently reconfigured plant which has been recklessly rushed into completion without the proper safety checks and required maintenance procedures. Unfortunately the president does not have time to read the report before a 6.1 magnitude earthquake strikes and destabilises the plant to the extent that it edges towards meltdown.

Unusually, in a sense, the president is a good man who genuinely wants to do the best for his people even if he sometimes ignores sensible advice out of a desire to protect those on the ground. Unfortunately, he is at the mercy of a corrupt cabinet headed by a scheming prime minister intent on withholding information in order to push the president into cynical decision-making models predicated on the idea of the needs of the many outweighing the needs of the few but which mainly relate to the needs of the prime minister and his cronies in the nuclear industry.

The man in charge of the plant has only been there a few weeks and has no nuclear industry experience. His second in command is a company man and his loyalty lies with his employers – he needs to keep everything functioning and ensure the plant will not be decommissioned. The only voice of reason is coming from the chief engineer who wrote the whistle blowing report and nobly remains on site throughout the disaster putting himself at grave personal risk trying to ensure the plant does not pose a greater danger to those in the immediate vicinity.

Claiming a desire to avoid mass panic, the government attempts to order a media blackout, giving little or no information to civilians stranded in the town and fitting communications jammers to prevent the spread of information. The town is eventually given an evacuation order and orderly transportation to a shelter but once there the townspeople are kept entirely in the dark. When they become aware of the full implications of the disaster and try to leave independently, they are locked in while officials flee and leave them behind.

Conversely, the emergency services are hemmed in by regulations which state they cannot act because they would be putting themselves at unacceptable risk. Kang Jae-hyuk, despite his earlier irritation with his place of work, abandons his own cynicism to walk back into the disaster zone to help his friends still trapped inside. The president nobly refuses to order anyone to tackle the disaster directly knowing that it would mean certain death but opts to appeal for volunteers willing to sacrifice themselves for the greater good. Unexpectedly, he finds them. The president is well-meaning but ineffectual, the government is corrupt, and the emergency services apparently overburdened with regulation while under-regulated commercial enterprises put lives in danger. The only force which will save the Korean people is the Korean people and its willingness to sacrifice itself for the common good even in the face of such cynical, self-interested greed.

Despite the scale of the disaster, Pandora takes its time, eschewing the kind of black humour which typifies Korean cinema disaster or otherwise. Serious rigour, however, goes out of the window in favour of overwrought melodrama, undermining the underlying messages of widespread societal corruption from corporations cutting corners with no regard for the consequences to politicians playing games with people’s lives. The powers that be have opened Pandora’s Box, but the only thing still trapped inside is men like Kang Jae-hyuk whose disillusioned malaise soon gives way to untempered altruism and eventually offers the only source of hope for his betrayed people.

Original trailer (English subtitles available from menu)

Walk a mile in a man’s shoes, they say, if you really want to understand him. If Kim Yong-gyun’s The Red Shoes (분홍신, Bunhongsin, 2005) is anything to go by, you’d better make sure you ask first and return them to their rightful owner afterwards without fear or covetousness. Loosely based on the classic Hans Christian Andersen tale this Korean take replaces dancing with murder and also mixes in elements from other popular Asian horror movies of the day, most notably

Walk a mile in a man’s shoes, they say, if you really want to understand him. If Kim Yong-gyun’s The Red Shoes (분홍신, Bunhongsin, 2005) is anything to go by, you’d better make sure you ask first and return them to their rightful owner afterwards without fear or covetousness. Loosely based on the classic Hans Christian Andersen tale this Korean take replaces dancing with murder and also mixes in elements from other popular Asian horror movies of the day, most notably  Yoo ha takes us back to the 1970s for some Gangnam Blues (강남 1970, Gangnam 1970) in a sorry tale of fatherless men caught up in dangerous times of ambition and avarice, very much at the bottom of the heap and about to be eclipsed by the “new world” currently under construction. Back then, Gangnam really was all just fields, owned by farmers soon to be cheated out of their ancestral lands by enterprising gangsters engaged in a complicated series of land grab manoeuvres, anticipating the eventual expansion of the bursting at the seams capital. Far from the shining city of today, Gangnam was a wasteland frontier town, the sort of place where a man can make a name for himself trading on his wits and his fists alone.

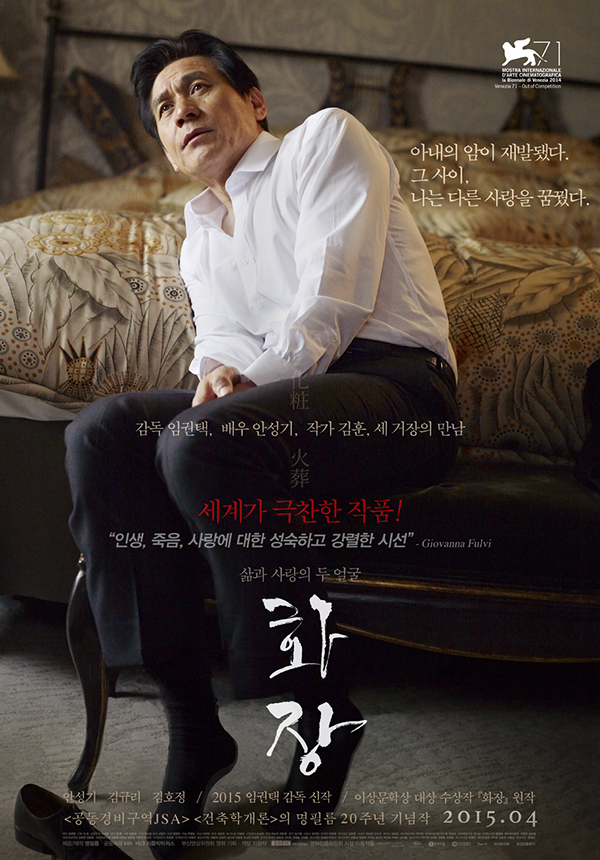

Yoo ha takes us back to the 1970s for some Gangnam Blues (강남 1970, Gangnam 1970) in a sorry tale of fatherless men caught up in dangerous times of ambition and avarice, very much at the bottom of the heap and about to be eclipsed by the “new world” currently under construction. Back then, Gangnam really was all just fields, owned by farmers soon to be cheated out of their ancestral lands by enterprising gangsters engaged in a complicated series of land grab manoeuvres, anticipating the eventual expansion of the bursting at the seams capital. Far from the shining city of today, Gangnam was a wasteland frontier town, the sort of place where a man can make a name for himself trading on his wits and his fists alone. The 102nd film from veteran Korean film director Im Kwon-taek may appear close to the bone in its depictions death, suffering, and the long look back on a life filled with the quiet kind of love but Revivre (화장, Hwajang) is anything but afraid to ask the questions most would not want to hear as the light dwindles. The inner journey is just too hazy, as one man puts it, unknowingly commenting on the human condition, yet Im does manage bring us nicely into focus, if only for a moment.

The 102nd film from veteran Korean film director Im Kwon-taek may appear close to the bone in its depictions death, suffering, and the long look back on a life filled with the quiet kind of love but Revivre (화장, Hwajang) is anything but afraid to ask the questions most would not want to hear as the light dwindles. The inner journey is just too hazy, as one man puts it, unknowingly commenting on the human condition, yet Im does manage bring us nicely into focus, if only for a moment.