The hero of Gao Peng’s A Long Shot (老枪, lǎo qiāng) is forever reminding himself to “regain your focus”, yet in other ways it’s something that he’s making an active choice not to do and that others wish he wouldn’t. Set amid the chaos of China’s mid-90s economic reforms, the film suggests that Xue Bing has little other option than to tune himself out and avoid being a direct part of the corruption all around him as he has little power to stop it.

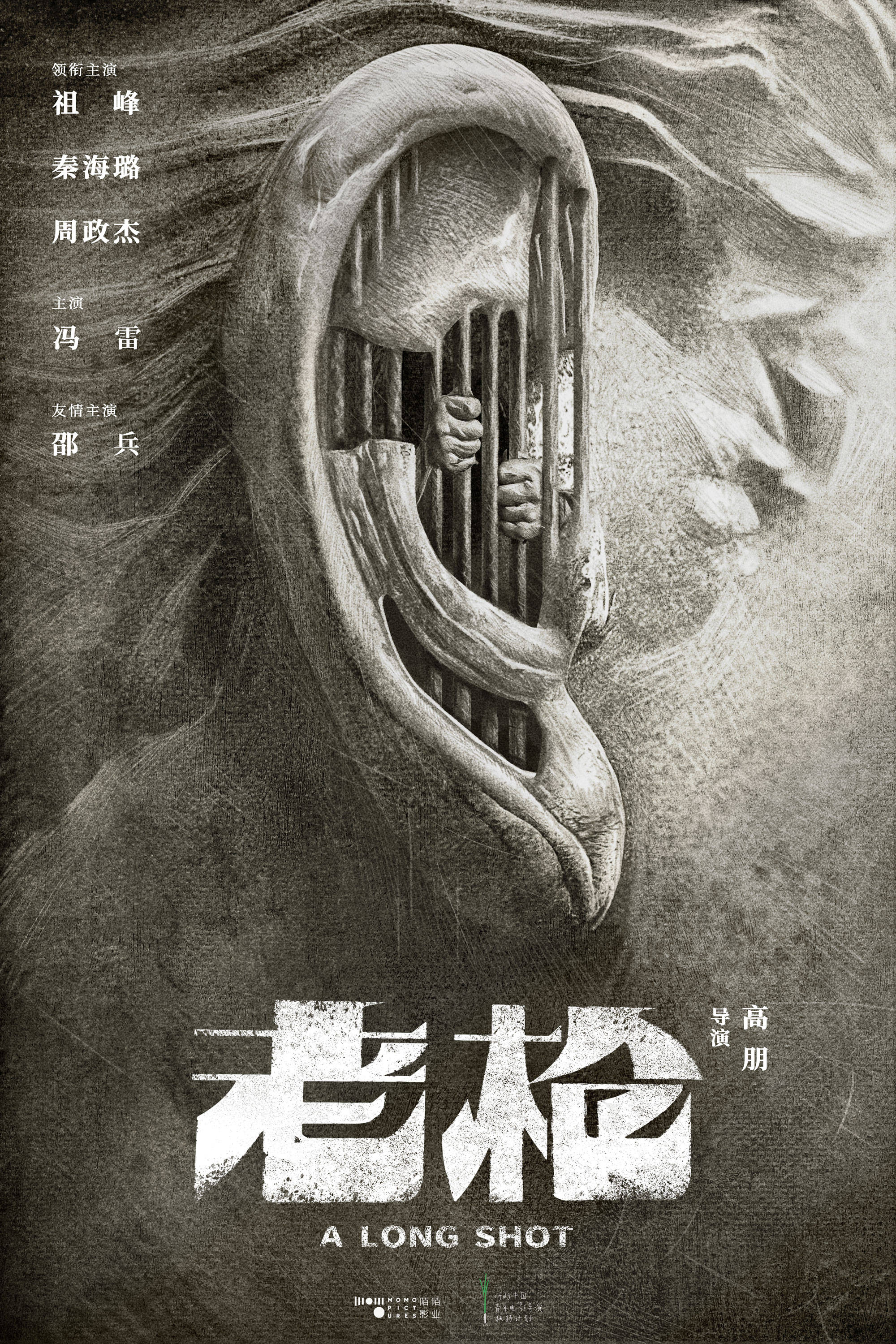

In a prologue set five years before the main action, Xue Bing (Zu Feng) had been a sharpshooter on the national team but is told that he has experienced hearing loss which may affect his balance and is subsequently let go. The hearing loss is perhaps symbolic of the fact that Xue Bing does not listen to the lies and double talk around him and maintains an integrity that is nothing but irritating to his morally compromised colleagues. On the other hand, he later tells Xiao Jun (Zhou Zhengjie), a teenage boy to whom he’s become a kind of father figure, that staring at a bull’s eye all your life isn’t good for your eyes hinting at his problematic hyper focus in which he’s just trying to keep his head down and do the best job he can under the circumstances.

But the circumstances are grim for everyone. Now with shaggy hair and a look of disappointment in his eye, Xue Bing works as a security guard at a moribund ferroalloy factory where the workers haven’t been paid in years as the nation goes through a number of complex economic reforms that are changing the face of the nation and giving rise to a new class of wealthy elites who’ve gained their riches through immoral and exploitative means. With people not being paid, thefts are a common occurrence but the security guards have turned to taking bribes, tacitly turning a blind to equipment going missing if the thieves are willing and able to pay a small fee. Xue Bing doesn’t like to go along with this and avoids joining in, but is powerless against the other guards including his boss Chief Tian (Shao Bing).

The film frames the factory as a microcosm of the wider society which has become a vicious circle of corruption. But on the other hand, the workers guards, and even in the management see themselves as taking what was rightfully theirs but has been unfairly denied them. The workers steal from their employer because their wages weren’t paid, the guards aren’t getting paid either so they extort the workers and rip off the company, while the management know the factory’s effectively bust so they’re asset stripping while they still can. Chief Tian runs into one of the thieves who’s since started a “trading company” having taken some cues from a Russian working at an equally moribund shipyard where he’s no longer monitored by the authorities and has been selling off warships as scrap hinting at the disintegration of post-war communism and the resulting capitalist free for all that followed.

Xiao Jun, the son of a woman Xue Bing thinks he’s in a relationship with but the reality is somewhat ambiguous, is caught amid this crossfire as a young man coming of age in complicated times. He resents the corruption he sees around him and bonds with Xue Bing thinking he’s a straight shooter only to be disappointed by his defeated complicity which he also sees as a kind of unmanliness. Xiao Jun’s mother, Jin (Qin Hailu), had been trying to run her own business but later gets a job in a nightclub that seems to be sex work adjacent thanks to her relationship with another corrupt businessman, Mr Zhao. She remarks to Xue Bing that there are so many ways to earn a living these days she doesn’t understand why anyone would go back to the factory, laying bare the wholesale change in the society. Xiao Jun has taken up with a gang of seeming delinquents who frequently loot the factory complex, but even they are only taking what they think is theirs as one of the boy’s fathers was killed in a workplace accident and the family was only given a certificate of commendation rather than financial compensation for the father’s lost wages without which they are unable to support themselves.

The guards have been told they’ll finally get paid after the company’s 40th anniversary celebrations, with corrupt manager Sun telling Tian he’ll need his help to keep the others in line when he presses him and is finally told they’ll only get two months’ worth of the back pay they’re owed. Xue Bing is told Sun was selling off the lathe machines in order to pay the workers, and it seems like he believes them naively falling for their greater good narrative while Xiao Jun seems on a collision with adult hypocrisy refusing to sign a false confession to get the managers off the hook. Gao lends Xue Bing’s world a greying hopelessness in which the only two choices are to close his eyes and ears or go down fighting, closing with a lengthy shootout in which firecrackers mingle with gunshots masking the sound of rebellion from a continually unheard underclass.

A Long Shot screened as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.