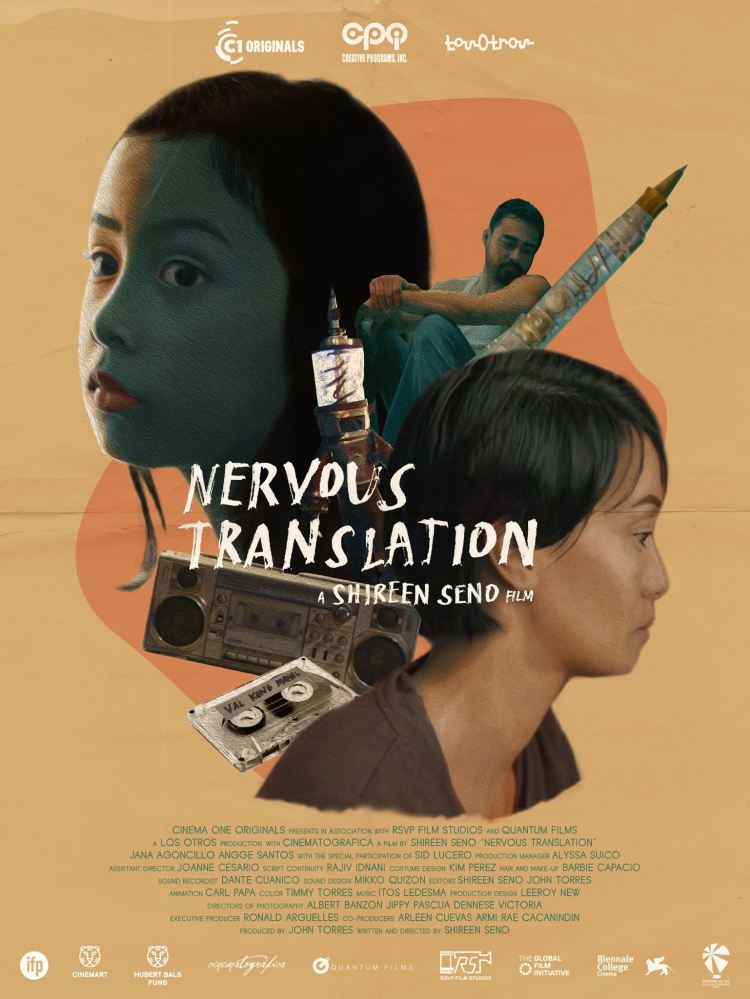

If you knew of a device which would give you “a beautiful human life”, wouldn’t you want to get hold of it? The heroine of Shireen Seno’s Nervous Translation longs to do just that, tantalised by its promise of the ability to write simply and convey one’s thoughts to others with ease. Living in anxious times, Yael is an anxious little girl who knows little of the chaos going on outside her ordinary home but continues to find herself uncertain even here.

If you knew of a device which would give you “a beautiful human life”, wouldn’t you want to get hold of it? The heroine of Shireen Seno’s Nervous Translation longs to do just that, tantalised by its promise of the ability to write simply and convey one’s thoughts to others with ease. Living in anxious times, Yael is an anxious little girl who knows little of the chaos going on outside her ordinary home but continues to find herself uncertain even here.

Yael (Jana Agoncillo), often home alone, is a shy little girl left largely to her own devices until her harried mother, Val (Angge Santos), gets back from her job in a shoe a factory. Taking some advice from her absent husband a little too literally, she “retires” from being a mother for the first 30 minutes after arriving home, insisting on total silence and shutting herself away in her room as if her daughter did not exist. Meanwhile, Yael pines for the father she only really knows from the voice recordings he sends home on cassette tape and which she is not, technically, allowed to listen to despite their being addressed both to her and her mother. On the tapes, her father seems to be employing some kind of code so the messages will be suitable for a little girl’s ears (her mother is not quite so careful in her replies), but talks of how much he misses his family and regrets missing out on so much of his young daughter’s life.

Painfully shy, Yael’s only other real contact is a friend from school, Wappy, whom she calls up on the telephone for a “mad minute” of maths. It’s also to Wappy that she turns when she realises she’s accidentally taped over quite a sensitive moment in one of father’s messages, hoping her male friend could help by putting on a deep voice to re-record the words she’s already memorised only for him to remind her that he’ll still be eight years old and probably no help even if they wait ’til later.

Yael’s innocent attempts to repair the broken tape hint at both her childish worldview and her ongoing desire to “translate” herself through the medium of mimicry. She is captivated by a very bubble-era Japanese ad on television for the “Ningen Pen” (human pen) which promises that it is easy to write with and makes expressing yourself to others simple. One could, of course, say this is true for almost any kind of pen but Yael, still a child, is more interested in the promise of the shiny magic gadget than actively keyed into the power of writing as a path out of her shyness.

We never learn the reason for Yael’s bandages or the skin complaint which seems to affect only her arms and possibly keeps her wary of other children, at least if her cousin’s “are you some kind of mummy?” question is anything to go by. We do know, however, that her father was shy, like her, and also had a physical “deformity” as someone later puts it in that one side of his body was much shorter than the other. His twin brother (Sid Lucero), by contrast, is a handsome rockstar now living the highlife in Japan where his wife complains about their expat existence and her inability to make friends with the “picky” Japanese. Possibly down to the soap operas which too closely reflect her own life, Yael seems to pick up on an awkward tension between her mother and uncle but in the end he is the one who tries to “restore” the family by fixing the broken boom box and saving Yael’s bacon by swapping out the damaged tape for another one at just the right moment.

Given the external chaos, however, the family cannot yet be fully repaired. The adults are just as lost and confused as Yael, struggling to parse the sudden changes in society and in their own lives. Val resents her husband’s absence and the economic instability which provoked it while also resenting her labour intensive job in the shoe factory (perhaps a slightly ironic touch given the former first lady’s mania for footwear). She has no time for her daughter, and perhaps resents also the loss of her youth in service of the traditional family life of which she has now been robbed, longing for the intimacy of her long absent husband. Yael “translates” all of her anxieties into a rich fantasy life, reordering her experience in miniature as she cooks tiny meals on a candlelight stove, determined to get the money together to buy “a beautiful human life” in the form of a shiny Japanese pen. Charmingly whimsical but with irresolvable anxiety at its core, Nervous Translation is a beautifully fraught picture of difficult childhood set against the backdrop of political upheaval which manages to find the sweetness in its heroine’s self-sufficiency even while casting her adrift in uncertain times.

Nervous Translation was streamed online by Mubi and screened as part of the Aperture: Asia & Pacific Film Festival courtesy of Day for Night.

Festival trailer (dialogue free)

“Why is there so much madness and too much sorrow in the world? Is happiness just a concept? Is living just a process to measure man’s pain?” asks a key character towards the end of this eight hour film, but he might as well be speaking for the film itself as its director, Lav Diaz, delivers another long form state of the nation address. This is a ruined land peopled by ghosts, unable to come to terms with their grief and robbing themselves of their identities in an effort to circumvent their pain. Raw yet lyrical, Diaz’s lament seems wider than just for his damaged homeland as each of its sorrowful, disillusioned warriors attempts to reacquaint themselves with world devoid of hope.

“Why is there so much madness and too much sorrow in the world? Is happiness just a concept? Is living just a process to measure man’s pain?” asks a key character towards the end of this eight hour film, but he might as well be speaking for the film itself as its director, Lav Diaz, delivers another long form state of the nation address. This is a ruined land peopled by ghosts, unable to come to terms with their grief and robbing themselves of their identities in an effort to circumvent their pain. Raw yet lyrical, Diaz’s lament seems wider than just for his damaged homeland as each of its sorrowful, disillusioned warriors attempts to reacquaint themselves with world devoid of hope.