Domestic power struggle meets oppressive patriarchal social codes and entrenched class prejudice in Choi Eun-hee’s lighthearted marital drama, Daughter-in-Law (민며느리, Minmyeoneuli, AKA The Girl Raised as a Future Daughter-In-Law). One of the biggest stars of Korean cinema’s golden age, Choi was only the third woman to direct a feature film and the first to direct herself as the leading lady, adapting a popular radio serial in which a pure hearted young girl finds herself suffering while patiently fulfilling the role of a dutiful daughter-in-law to a tyrannical middle-aged woman. Though the film may eventually reinforce traditional gender roles and the patriarchal norms of the conventional marriage it also subtly undercuts them in its final bid for female solidarity as well as in the surprisingly frank depiction of the sexually active relationship between the middle-aged in-laws.

Perhaps surprisingly, the film opens with a montage sequence of a young woman doing laborious household tasks while the title song muses on the difficulties of married life. For young Jeomsun (Choi Eun-hee), the problems are compounded as we discover she was in effect sold into marriage because of her once wealthy family’s poverty and as her intended husband is still only a child is treated as an unpaid housekeeper by her harridan of a mother-in-law, Mrs Kim (Hwang Jung-seun). “Serve your parents and respect your husband, that’s this country’s way” Mrs Kim reminds her, continually dissatisfied with everything but mostly that she isn’t getting enough respect or attention as the head of the household (in the domestic sense at least).

As thoughtlessly cruel as she often appears to be, Mrs Kim’s behaviour can perhaps be seen as merely an attempt to leverage the only power she will ever have as the matriarch in her own house, a power made all the greater by the fact her son is still a child and her future daughter-in-law only afforded a liminal space within the family hierarchy. She continually reminds her husband (Kim Hie-gab) and Jeomsun that she too had a mother-in-law who treated her badly, often making her work through the night, and so her treatment of Jeomsun is a way of paying down the system, a facet of the “custom passed down through the generations”. Having been badly treated herself, she relishes her new sense of power and treats her daughter-in-law badly as misdirected payback for her own youthful suffering.

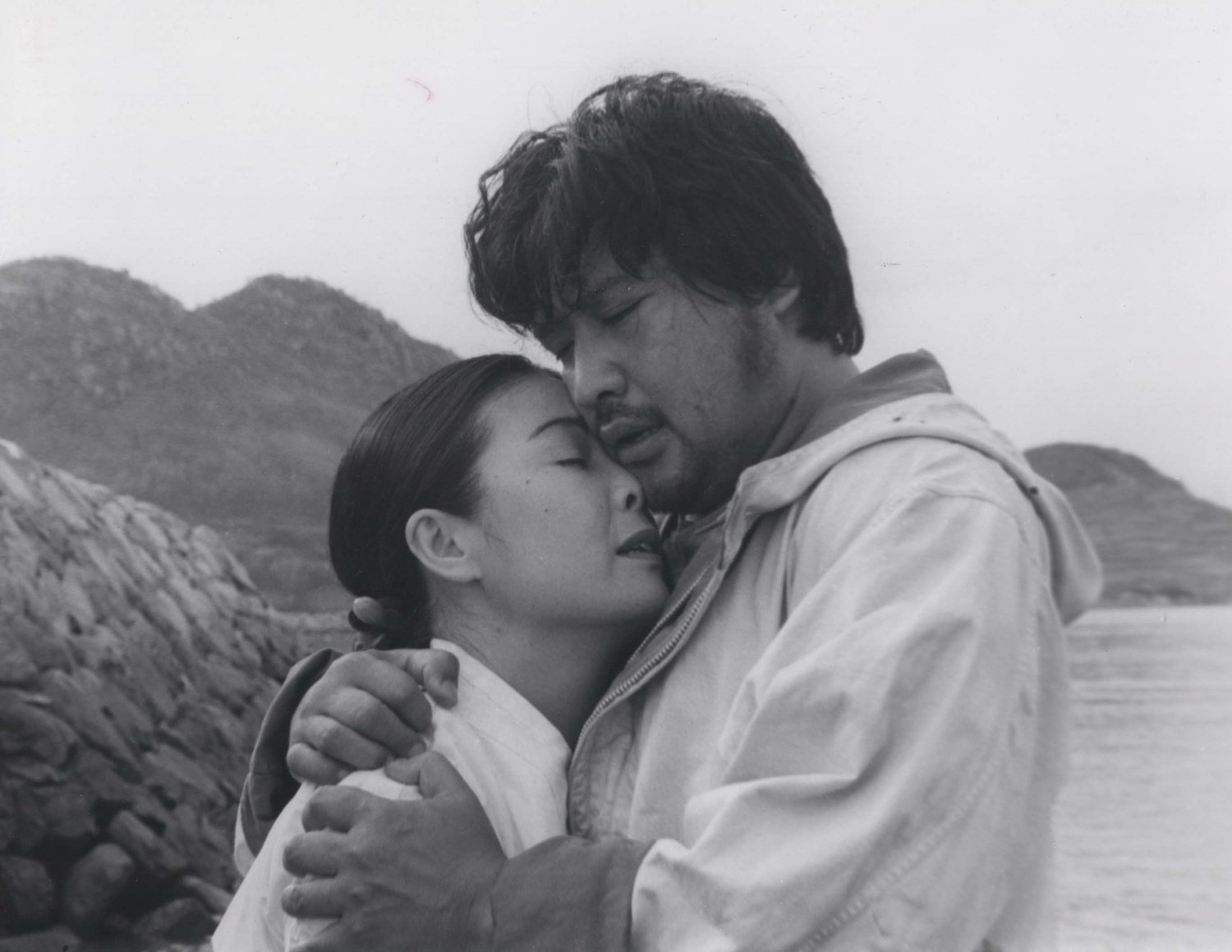

Jeomsun herself has internalised a sense of the system’s righteousness, fully believing that she must do her “duty” as a good daughter-in-law even when her own mother points out that her in-laws are hardly doing their duty when they wilfully mistreat her. Added to notions of patriarchal subjugation is a further class dimension that leaves Jeomsun at their mercy because she has become impoverished, her mother having consented to her marriage only reluctantly in an attempt to avoid having to sell the family house. Jeomsun had been in love with a local man, Sugil (Park No-sik), but felt their union was impossible while her father was alive because he was of a lower social class and continues to believe it improper even after his death with only her mother lamenting that she wishes she had found a way that her daughter could have had a happier life marrying a man she loved. For his part, Sugil attempts to buck the system by continuing to pursue her, hoping to “buy” her back off the Kims after raising money while the marriage remains unconsummated and therefore unofficial.

Choi’s age, then in her late 30s though presumably playing the part of a young woman in her late teens or early 20s, further adds to the incongruous inappropriateness of her position in the household as the future wife of a boy who is still quite clearly a child. Yet the young master, Bokman, appears to dote on her, often taking her side against his mother but in the end unable to defend her, too afraid of Mrs Kim to tell the truth and risk having to take responsibility for his actions preferring to let Jeomsun pay for them instead. In an interesting role reversal, it’s Mr Kim who is the perpetual peacemaker, a kind and patient man who quite clearly loves his firecracker wife despite her harsh demeanour. The slightly comedic depiction of their cheerfully active sex life as a middle-aged couple is perhaps at odds with the often prudish times, but also softens Mrs Kim’s otherwise difficult character until such time as she’s tricked into a moment of self-realisation in the recognition that her resentment of Jeomsun is really a reflection of her maternal jealousy and therefore entirely unfair.

It’s this momentary epiphany that brokers an opportunity for a new female solidarity not only between Jeomsun and her mother-in-law but also with her own mother who must then find the magnanimity to forgive Mrs Kim for treating her daughter so badly in the first place. What began as a tale of patriarchal cruelties, a young woman sold as a wife to a spoilt child at the expense of her own romantic fulfilment, ends with a wilful reversal of the “custom passed down through the generations” as Mrs Kim agrees to cede some of her power in treating her daughter-in-law as more of an equal while making space to welcome her mother, another mother-in-law, into her home. “We all have to live according to our duties” Jeomsun had sadly explained to her former love, yet what she discovers is that duty is a two way street and lies perhaps more in mutual compassion than in slavish devotion to outdated tradition.

Daughter-in-Law is currently available to stream in the UK as part of the Korean Cultural Centre UK’s Korean Film Nights: Filming Against the Odds where it will be followed by Choi Eun-hee’s second film as a director A Princess’ One Sided Love on 27th May. Other films streaming in the season include Park Nam-ok’s The Widow (streaming throughout), Li Mi-rye’s My Daughter Rescued From The Swamp and Lee Seo-gun’s Rub Love (both 10th June).