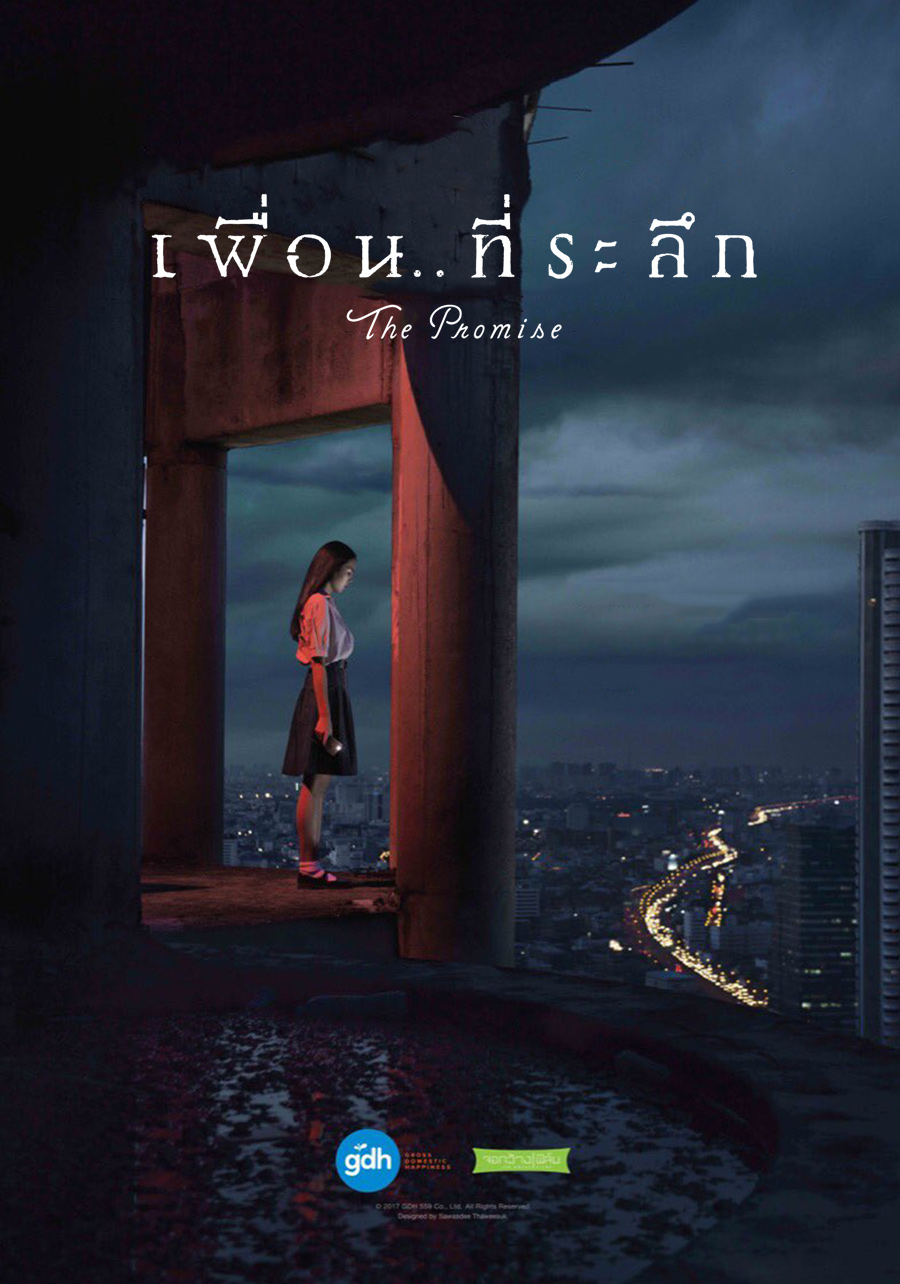

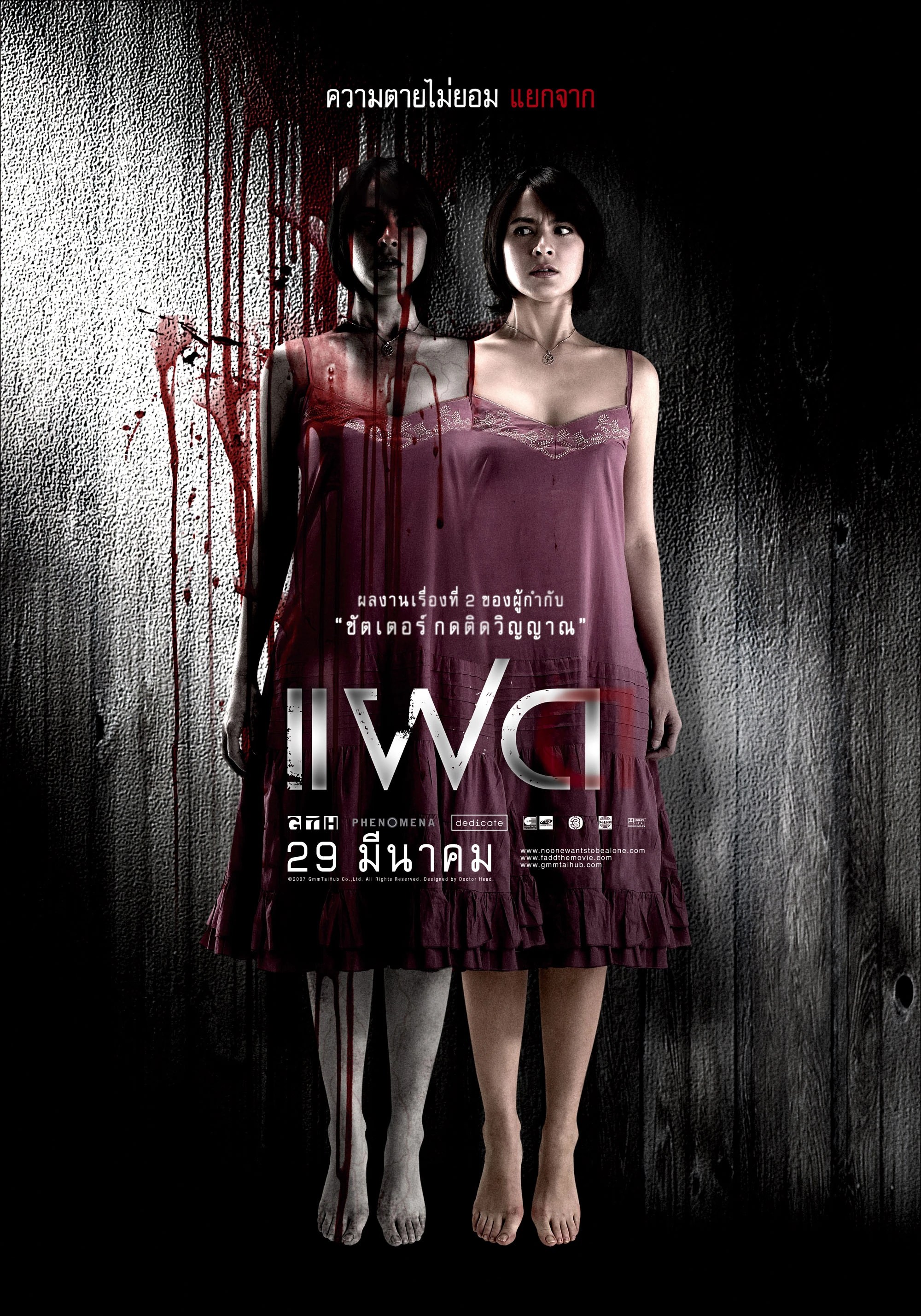

A young woman returns to her apartment in Seoul to find the lights don’t work. She begins to feel uneasy, as if there’s a presence around her she can’t see or hear. Slowly, she moves towards the source of her discomfort, but the lights soon come back on. This isn’t a haunting, it’s a party. Her devoted boyfriend Wee (Vittaya Wasukraipaisan) has organised a surprise birthday celebration, though Pim (Marsha Wattanapanich) is indeed a haunted woman attempting to outrun her ghosts in a new country a world away from the nexus of her trauma.

This is just one of many ways in which Banjong Pisanthanakun and Parkpoom Wongpoom attempt to misdirect us while foreshadowing Pim’s eventual confrontation with ghosts of her past on returning to Thailand after her mother suffers a stroke and is hospitalised. A brief prologue sequence had seen her mother sewing a dress that’s oddly shaped, we later realise intended for her daughters who are conjoined twins. A guest reading the tarot at Pim’s party had hinted that something she’s lost would soon return, or else someone to whom she’d broken a promise would come back seeking recompense. This soon proves to be true, Pim haunted by the spectre of her sister Ploy (also played by Marsha Wattanapanich) who passed away unable to adjust after Pim’s apparently unilateral decision to separate.

It’s for this reason that Pim feels intense guilt, convinced that she killed her sister in breaking their promise to always stay together because she desired individual fulfilment. To that extent, some might wonder if the ghost Pim sees is “real” or merely a manifestation of her unresolved trauma. Wee eventually convinces her to see a psychiatrist, who is also a good friend of his, who tells him that Pim is suffering from a delusion while advising her to try to make peace with herself over her sister’s death if she wants to stop seeing the ghost. But perhaps there really is something dark and malevolent, a resentful spirit haunting her family home which is otherwise full of childhood memories. Pim flips through old photos all featuring her and her sister living their shared life of enforced closeness that is at first blissfully happy in its isolation but then suffocating and constrained.

Nevertheless, though it’s Pim who’s left “alone” in being the one left behind, it’s also true that Pim’s actions have left Ploy “alone” too, only on the other side. The film plays into their nature as twins who represent two halves of one whole rather than two separate beings and locates the source of trauma in their separation as if they must in some sense be reunited in order to exorcise its taboo. In many ways, the psychological drama revolves around a quest for identity as Pim tries to reassert herself in the face of Ploy’s reflection, to become the whole rather than an orphaned part of it, while in other ways affecting a persona that is not quite her own. One cannot take the place of the other, just the new dog the pair get after moving to Thailand cannot replace their old one even if as Pim says they are otherwise identical.

Yet Pim wonders if it was alright to desire an individual future, choosing herself over Ploy and thereby condemning her to a life of loneliness. To that extent, her dilemma is that of a contemporary woman torn between familial devotion and personal fulfilment, though of course, her words turn out to have a hidden implication suggesting that all is not quite as it seems even if she begins to confront her trauma by finally explaining the circumstances of her separation to an ever supportive but increasingly worried Wee. As the tarot reader had implied, perhaps all promises must in the end be fulfilled as the grim conclusion suggests, literally burning down the house as if to purify this space and restore order in uniting the sisters in an eternal embrace, alone together. Banjong Pisanthanakun and Parkpoom Wongpoom engineer a slowly creeping sense of dread in the gothic eeriness of Pim’s family mansion while edging towards the fatalistic conclusion in which a kind of balance is finally restored, the sisters are both separated and united once again two halves one perfect whole.

Alone is available as part of Umbrella Entertainment’s Thai Horror Boxset.

International trailer (English subtitles)