Towards the end of Lino Brocka’s Bona (Nora Aunor), the heroine recounts a dream she had in which she tries to escape a fire but finds herself met only by more flames. The inferno she attempts to outrun is that of the oppressive patriarchy of a fiercely Catholic society in which men can do as they please, but women are held to a different standard and in the end have little freedom or independence.

Brocka opens with a lengthy sequence of a religious festival in which the suffering Mary is carried through the streets on the shoulders of men. Teenager Bona looks on but worships at a different altar, that of Gardo (Phillip Salvador), a struggling bit-player trying to make it in the Philippine film industry. What becomes apparent is that her fascination with Gardo is borne of her desire to escape her family home and the tyrannical reign of her authoritarian father (Venchito Galvez) who berates her for not helping her mother out enough with her business and later whips her with his belt because she stayed out too late.

Though her family is quite middle class, Bona instals herself in Gardo’s home in the slums in search of greater freedom but ends up becoming his skivvy or perhaps even a kind of maternal figure patiently taking care of him while he continues to bring other women home and even charges her with taking another teenage girl he’s got pregnant to the doctor (who charges him “the same as before”) for an abortion. It’s possible that in Gardo she sees a different kind of masculinity, a performance of manliness, but gradually comes to realise he’s nothing more than an opportunistic lothario with no emotional interest in women let alone her.

But by then, it’s too late. She’s stuck in a kind of limbo barred from returning home to her family because of her status as a fallen woman who has shamed them by living with a man she is not married to. Even once her father dies, her mother warns her to avoid her brother because his rage is indescribable and he does indeed drag her out of the funeral by her hair while issuing threats of violence. Perhaps what she was looking for was greater independence or an accelerated adulthood with the illusion of freedom, but she can only find it by relying on Gardo rather than attempting to chart her future alone. We can see that other women in the slum are in much the same position, loudly arguing with their husbands who cheat, laze around drinking, and permit them little possibility for any kind of individual fulfilment.

Yet there is a moment where Bona seems free, ironically dancing at the wedding of a young man, Nilo (Nanding Josef), who she’d turned down but now perhaps regrets it comparing the conventional married life she might have had with him to the prison she’s designed for herself in her life with Gardo. Nilo may be the film’s nicest man, but at the same time he’s still a part of the system that Bona can’t escape. In fact, the only woman fully in charge of herself is a wealthy widow who later buys Gardo’s, not exactly affections, but perhaps loyalty. “She’ll do,” he less than romantically explains after admitting to marrying her for the convenience of her money oblivious of the effect the news may have on the by now thoroughly humiliated Bona whose rage is just about to boil over.

Unable to free herself from this fanatical devotion or to find possibility outside it, Bona is trapped by her desires and marooned in a kind of no man’s land in which she cannot exist as an independent person but only as servant to a man. “I’ll just serve you,” she explains on moving in and thereafter slavishly catering to all of Gardo’s whims while he largely ignores her. She hasn’t so much escaped her father’s house, but built a prison for herself from which she cannot escape despite her oncoming displacement. A creeping character study, the film finds the titular heroine searching for a way out of the fire only to find herself engulfed by flames with no real prospect of salvation amid the ingrained misogyny of a fiercely patriarchal society.

Bona screens Nov. 14 as part of this year’s San Diego Asian Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)

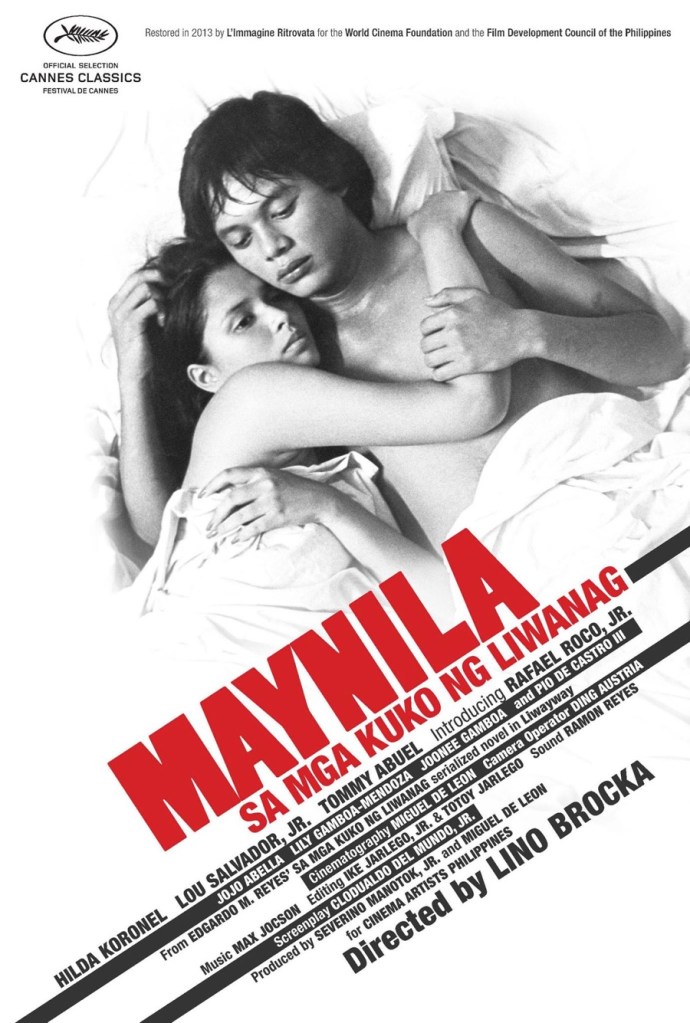

About half way through Lino Brocka’s masterpiece of Philippine cinema Manila in the Claws of Light (Maynila, sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag), the hero, Julio (Bembol Roco), sits watching the window where he thinks the woman he loves may be being held prisoner as a trio of guitar players strums out The Impossible Dream, unwittingly narrating his entire story. Julio is no Don Quixote but he has his own Dulcinea and, as the song says, without question or pause he is ready to march into hell for the heavenly cause of rescuing her from clutches of this cruel city. Not quite content to love pure and chaste from afar, Julio plays Orpheus descending into the underworld, plunged into a strange odyssey through a harsh and indifferent world driven by mutual exploitation and the expectation of violence.

About half way through Lino Brocka’s masterpiece of Philippine cinema Manila in the Claws of Light (Maynila, sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag), the hero, Julio (Bembol Roco), sits watching the window where he thinks the woman he loves may be being held prisoner as a trio of guitar players strums out The Impossible Dream, unwittingly narrating his entire story. Julio is no Don Quixote but he has his own Dulcinea and, as the song says, without question or pause he is ready to march into hell for the heavenly cause of rescuing her from clutches of this cruel city. Not quite content to love pure and chaste from afar, Julio plays Orpheus descending into the underworld, plunged into a strange odyssey through a harsh and indifferent world driven by mutual exploitation and the expectation of violence.