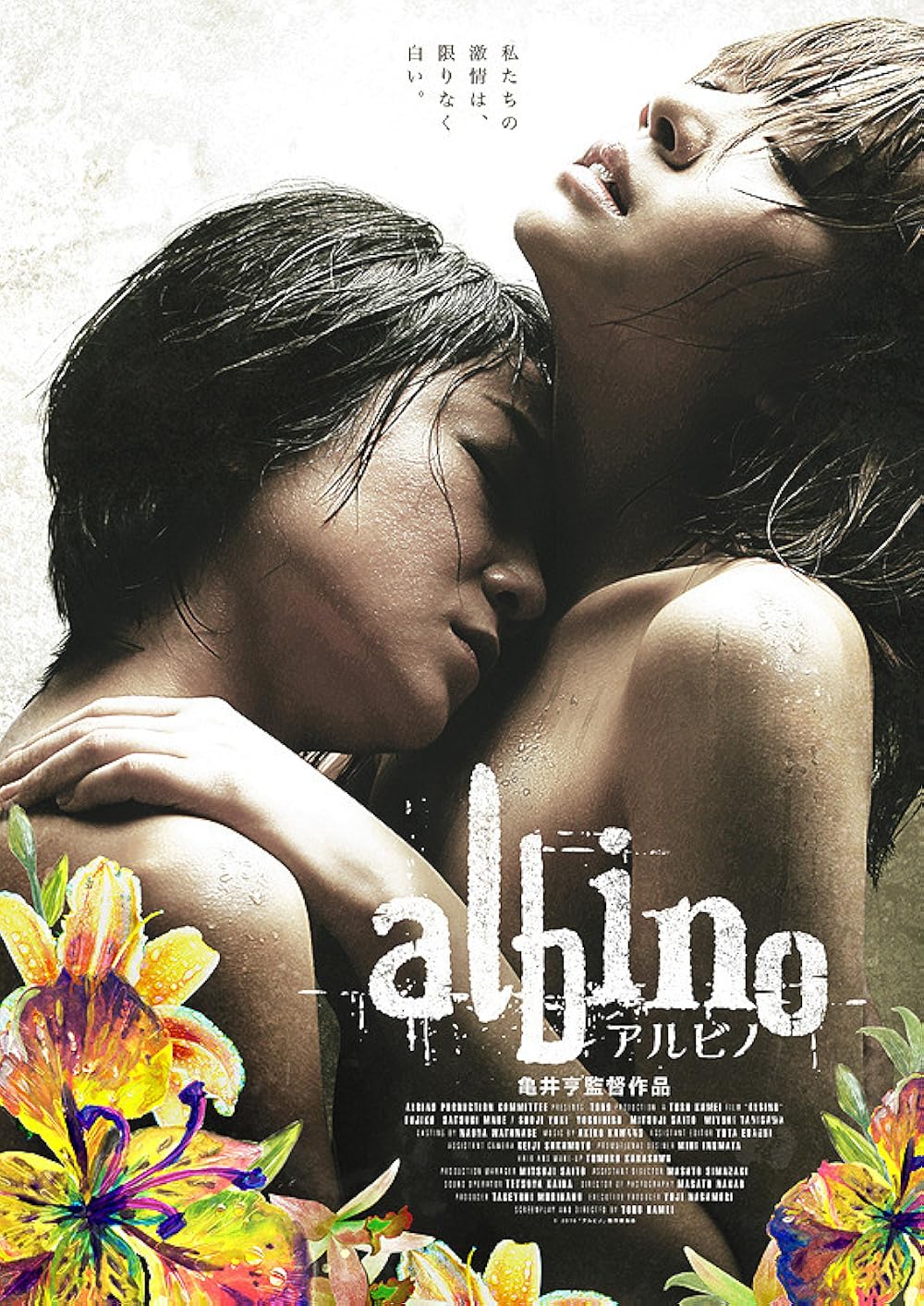

Two women struggle to free themselves from the abuses of a patriarchal and conservative society in Toru Kamei’s tragic lesbian romance, Albino (アルビノ). Though perhaps somewhat out of touch in its tacit implication that same sex love is inherently destructive, Kamei’s sensitive drama finds its marginalised heroines seeking mutual rescue but finding only temporary respite in the bubble of their love fraught as it is with danger and confusion as they each in their own way struggle to escape their respective prisons literal and self imposed.

Butch plumber Yashima (Fujiko) has always felt somewhat ill at ease, that her inside doesn’t match her out, and the disconnect has made her reluctant to associate with others. On a job one day she encounters a strange young woman, Kyu (Satsuki Maue), wearing a high school uniform who can’t seem to stop gazing at her. Yashima fixes the problem with her sink which was clogged with paper tissue, but is surprised when Kyu calls back and says it happened again. On her return visit, while Kyu’s stepfather is out, Kyu asks Yashima to have a look at the bathroom where she gingerly seduces her, both women perhaps surprised by the depth of their desire. Problematic age gap aside, the two women embark on a passionate sexual affair but struggle to free themselves from the forces which constrain them outside of their intense physical connection.

Hinting at a kind of gender dysphoria, Yashima lives as a man but feels pressured into conforming to conventional femininity. She’s the only woman at her job as a plumber, perhaps still stereotypically regarded as a male occupation, and simultaneously regarded as one of the boys made complicit in the misogynistic banter of her boss and colleague. Resented for her unwomanliness, she’s eventually assaulted by her skeevy vanmate who refuses to believe her when she says she has no interest in men. She implies that prior to her relationship with Kyu, she hadn’t considered other women but had perhaps thought of herself as male, and is immediately overwhelmed by her newfound desire. Meanwhile, she’s also dealing with familial trauma in her difficult relationship with her alcoholic mother who frequently turns up only to ask for money to spend on drink.

Kyu, meanwhile, is more directly oppressed, trapped in an abusive environment with violent stepfather who repeatedly rapes her, his tissues the ones which eventually clog the sink after she tries to wash them away. She claims that the uniform is a fashion statement, though the implication seems to be that her stepfather does not allow her out of the house even to go to school if indeed she is still a student despite her claims to the contrary. That might also explain why she continues to clog the sink and call the plumber, potentially alerting Yashima’s boss not to mention the colleague who seems to have realised there’s something going on, rather than simply ring her directly even after she’s really only coming for sex. Kyu makes a habit of giving Yashima hard candies after each of their meetings, Yashima eventually realising that they spell out the word “help”, but she remains too traumatised to escape convinced that her stepfather would find her wherever they went.

Somewhat awkwardly, the implication is that Yashima’s relationship with Kyu is the force which motivates her to accept her femininity, the younger woman transgressively kissing her after staining her lips with menstrual blood as if to ram the point home. Kyu meanwhile agrees that she too hates being a woman, though her resentment is perhaps more towards her constant victimisation, her utter powerlessness at the hands of the hands of the stepfather who abuses her and whom she cannot escape. Yashima too finds herself victimised as a woman, assaulted by her colleague who leaves by coldly telling her it was her own fault for refusing him, or perhaps simply for her “failure” to conform to conventional social norms, a crime for which he has punished her as means of correction. Yet they each struggle to free themselves, Kyu too traumatised to embrace her freedom despite her literal cry for help, while Yashima is continually punished for her atypical gender presentation. Only in sex do they find release. Shot with a detached realism which extends to the naturalistic though passionate, erotic love scenes Kamei’s melancholy drama offers little in the way of hope for either woman, subtly suggesting that their romance is a forlorn hope because there is no escape from the forces which oppress them in such a rigid and conformist society.

Trailer (no subtitles)

Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.

Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.