Where is the line between justice and vengeance? The grieving father at the centre of Anshul Chauhan’s December (赦し, Yurushi) is determined that the teenage girl who stabbed his daughter to death should never leave prison, but what he wants is a kind of equivalent exchange in that the person who stole his future along with his child’s should have no right to one herself. A more mainstream effort than either of his previous films Bad Poetry Tokyo and Kontora each of which dealt with similarly thorny themes, Chauhan’s unusually tense courtroom drama is the latest to put the legal system on trial while asking difficult questions about grief, guilt, and what exactly it is we mean when we talk about “justice”.

Seven years previously, 17-year-old Kana (Ryo Matsuura) stabbed her classmate Emi (Kanon Narumi) multiple times in a frenzied attack that resulted in her death. She was sentenced to 20 years in prison and has never attempted to deny her crime. It isn’t she who has asked for her sentence to be reviewed but an independent lawyer, Sato (Toru Kizu), who claims he’s doing it for “justice” though as Kana points out might have half an eye on compensation money she’d be able to claim for wrongful imprisonment if the case were successful. Sato seems to think it will be on the grounds that Kana was unfairly tried as an adult, mitigating circumstances were never brought to the defence’s attention, and the judge’s sentencing was swayed by personal feeling placing it outside of conventional guidelines that should be applied in cases like these.

For Emi’s parents, Katsu (Shogen) and Sumiko (Megumi), the appeal is a slap in the face. The couple have separated and while Sumiko has attempted to move on with her life, marrying a man she met in a support group for bereaved parents, Katsu has become a bitter alcoholic living a purgatorial existence of almost total inertia. Outraged, he is determined to make sure that Kana never leaves prison and is only sorry that she could not receive the death sentence because of her age, while Sumiko would rather not be involved at all, uncertain that she would be able to endure the emotionally draining process of another court case. They settle on presenting a united front, but discover that to do so is also to put themselves on trial while being confronted by a past neither has ever really faced.

The strain on Sumiko is evident as she walks along along a bridge at night and peers over the edge as if about to jump. She later learns that Kana had a mother too who did in fact take her own life after selling everything she owned to pay the compensation money that is used against them in court to imply that they’ve already been served “justice” in the form of monetary recompense from the defendant’s family which ought to declare the matter closed. Unlike Katsu, Sumiko had said her goal wasn’t vengeance but only to make sure that no other mother suffers as she has done, yet another mother already has for she lost a daughter too. Kana meanwhile has no one left to turn to even if she were released, she will have to make a new life for herself alone. Kana is herself victimised by an unforgiving society, the subtext suggesting that she was bullied for being the daughter of a single mother who was unable to fully care for her or provide the kind of material comfort children like Emi receive. The “happy family home” Katsu accuses her of destroying is also a symbol of everything Kana was denied but she did not kill out of jealousy or resentment only, ironically, to escape a kind of imprisonment and free herself of an oppressive bully.

Katsu says he’d kill her himself if he had the chance, but as Sumiko points out then he’d just end up in prison for the rest of his life with only his “righteousness” to comfort him. How could he claim to be any better? As Sato says, emotion has no place in a court of law. That’s why the law the exists and we mediate “justice” through a dispassionate third party to ensure the sentence is fair and not merely “vengeance”. Katsu certainly sees himself as a righteous man. In a repeated motif, Chauhan shows him taking the long way round by walking on the pathways of the grid-like forecourt leading to the courthouse while others hurriedly take the direct route crossing the squares at a diagonal angle. For him the answer is only ever black and white and he is very certain of his truths, but also blinded by his pain and unable to see that his desire for vengeance is more for himself than it is for Emi.

Only by accepting a painful truth can he begin to move past his grief, despite himself moved by Kana’s quiet dignity in which she admits her responsibility and suggests that she will never really be “free” even if she is released. What she offers, in her way, is peace allowing the bereaved parents to bring an end to their ordeal or least enter a new phase in their grief which allows them to move forward in memory rather than remaining trapped within the unresolved past. Perhaps in the end that’s what we mean by “justice”, a just peace with no more recrimination only sorrow and regret with renewed possibility for the future.

December screened as part of this year’s Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

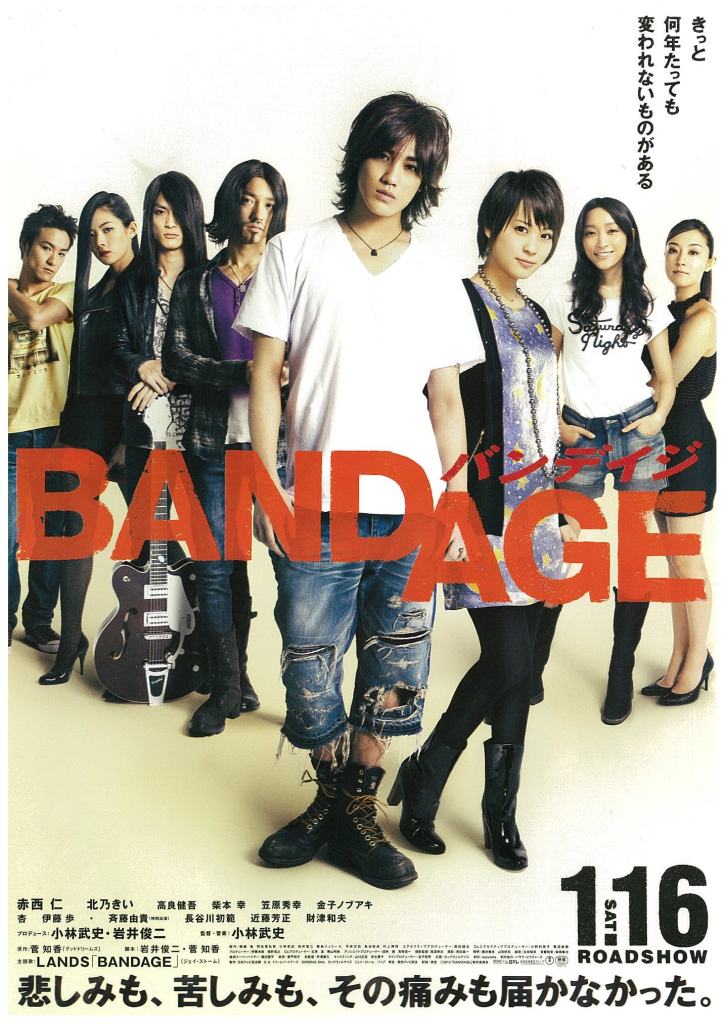

Japan was a strange place in the early ‘90s. The bubble burst and everything changed leaving nothing but confusion and uncertainty in its place. Tokyo, like many cities, however, also had a fairly active indie music scene in part driven by the stringency of the times and representing the last vestiges of an underground art world about to be eclipsed by the resurgence of studio driven idol pop. Bandage (Bandage バンデイジ) is the story of one ordinary girl and her journey of self discovery among the struggling artists and the corporate suits desperate to exploit them. One of the many projects scripted and produced by Shunji Iwai during his lengthy break from the director’s chair, Bandage is also the only film to date directed by well known musician and Iwai collaborator Takeshi Kobayashi who evidently draws inspiration from his mentor but adds his own particular touches to the material.

Japan was a strange place in the early ‘90s. The bubble burst and everything changed leaving nothing but confusion and uncertainty in its place. Tokyo, like many cities, however, also had a fairly active indie music scene in part driven by the stringency of the times and representing the last vestiges of an underground art world about to be eclipsed by the resurgence of studio driven idol pop. Bandage (Bandage バンデイジ) is the story of one ordinary girl and her journey of self discovery among the struggling artists and the corporate suits desperate to exploit them. One of the many projects scripted and produced by Shunji Iwai during his lengthy break from the director’s chair, Bandage is also the only film to date directed by well known musician and Iwai collaborator Takeshi Kobayashi who evidently draws inspiration from his mentor but adds his own particular touches to the material.