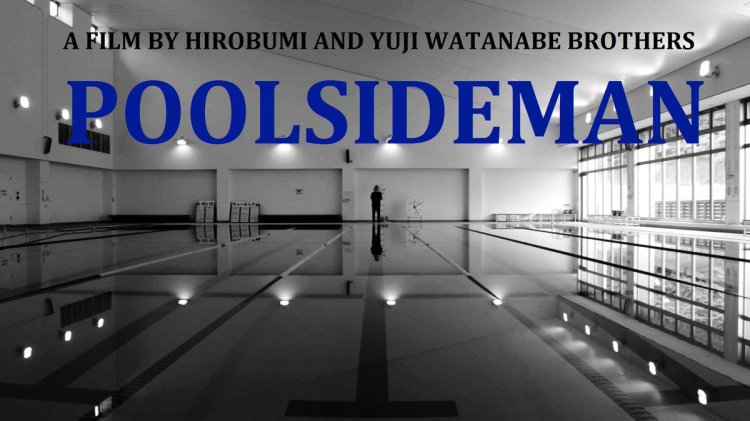

Around halfway through Poolsideman (プールサイドマン), the director himself playing an overly chatty colleague of the film’s protagonist, embarks on a lengthy rant about encroaching middle-age which is instantly relatable to those who find themselves at a similar juncture. He’s sure the world seemed better when he was a child, there wasn’t all of this distress and anxiety – everything just seemed like it would go on forever but time has inexplicably sped up with a series of rapid changes packed into recent years. The life of a poolsideman is improbably intense, or at least it is for Mizuhara (Gaku Imamura) whose days are all the same but filled with tension and the low simmer of something waiting to explode. Loosely inspired by the real life case of a man who left Japan for the Middle East with the idea of joining Isis, Poolsideman wants to explore why such a surreal thing might happen but finds it all too plausible.

Around halfway through Poolsideman (プールサイドマン), the director himself playing an overly chatty colleague of the film’s protagonist, embarks on a lengthy rant about encroaching middle-age which is instantly relatable to those who find themselves at a similar juncture. He’s sure the world seemed better when he was a child, there wasn’t all of this distress and anxiety – everything just seemed like it would go on forever but time has inexplicably sped up with a series of rapid changes packed into recent years. The life of a poolsideman is improbably intense, or at least it is for Mizuhara (Gaku Imamura) whose days are all the same but filled with tension and the low simmer of something waiting to explode. Loosely inspired by the real life case of a man who left Japan for the Middle East with the idea of joining Isis, Poolsideman wants to explore why such a surreal thing might happen but finds it all too plausible.

Mizuhara lives his life to strict routine. He gets up, turns on his radio to listen to the latest current events which mostly have to do with atrocities in the Middle East, eats breakfast and goes to work where he checks the lockers, patrols the pool, writes down various readings from the boiler system, and avoids his colleagues at break times by sitting outside or eating shortbread in his car before leaving for the day. He then goes to a local cinema where he is generally the only audience member and watches a violent film full of shooting, explosions and screaming, before grabbing a McDonald’s dinner and going home to bed.

His precious routine is broken when one of his colleagues informs him that they’re both being sent to a different pool to help out with staff shortages and asks if it would be possible to give him a lift because the pool is kind of far and he is only a “paper driver” – he has a license, but in reality doesn’t drive. It’s not as if Mizuhara can refuse, and so the pair drive together to another pool where they do the same job only in different surroundings.

The first hour or so of this two hour film is entirely taken up with Mizuhara repeating his near identical days while different news reports play recounting various international atrocities. Mizuhara never says anything and runs through each of his tasks with robotic precision but there’s something burning somewhere just behind his eyes. He looks at his colleagues with disdain as they gossip raucously in the rec room before taking himself outside to smoke or enjoy his daily shortbread alone in his car listening to more reports of terrible things happening abroad. Despite his apparent calmness, Mizuhara does indeed seem like the type who may just snap but deciding to join Isis is not necessarily the result most would have predicted.

Poolsideman’s main position is that blanket news coverage of horrific events may have strained Mizuhara’s already tense mind, leading him to believe the world is a worse place than it really is. Later, he switches his radio preferences but sticks with international politics as the world swings right – Trump, at that point still a candidate, suggests using nuclear weapons against “enemy” forces in the Middle East (something particularly worrying to the only nation so far with direct experience of nuclear attack) while Obama and Clinton attempt to talk sense. Britain votes for Brexit, against expectation and its own interest which, the commentator explains, is expected to lead to the destabilisation of Cameron’s government, extreme economic chaos, and political turmoil (on point, as it seems). Mizuhara carries on as before, cereal, toothbrushing, the pool, the cinema, and McDonald’s but there’s always the feeling that he’s standing on the edge about to jump and there’s no way to know how he might do it.

Less ostensibly humorous than And The Mudship Sails Away, Poolsideman still finds room for comedy though mostly through the amusing monologues delivered by Watanabe to the ever silent Mizuhara. Ranting about modern life from an inability to connect with the young to the noise pollution of hipster karaoke bars and ramen restaurants that make you book a ticket in advance, Watanabe’s observations are all too true but at least he works out his frustration with friendliness and good humour rather than internalising some kind of barely suppressed rage which threatens to boil over at any second. A kind of state of the nation address, Poolsideman gestures at the enemy within – the ignored, frustrated, and angry young man whose mind is ripe for hijacking when assaulted by a constant barrage of violence and political disturbance. Ending on a note of ambiguous tension Poolsideman wonders where all of this leads, or if it leads anywhere at all, but offers no easy answers for the problem of Japan’s disillusioned youth.

Poolsideman was screened at the 17th Nippon Connection Japanese Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)