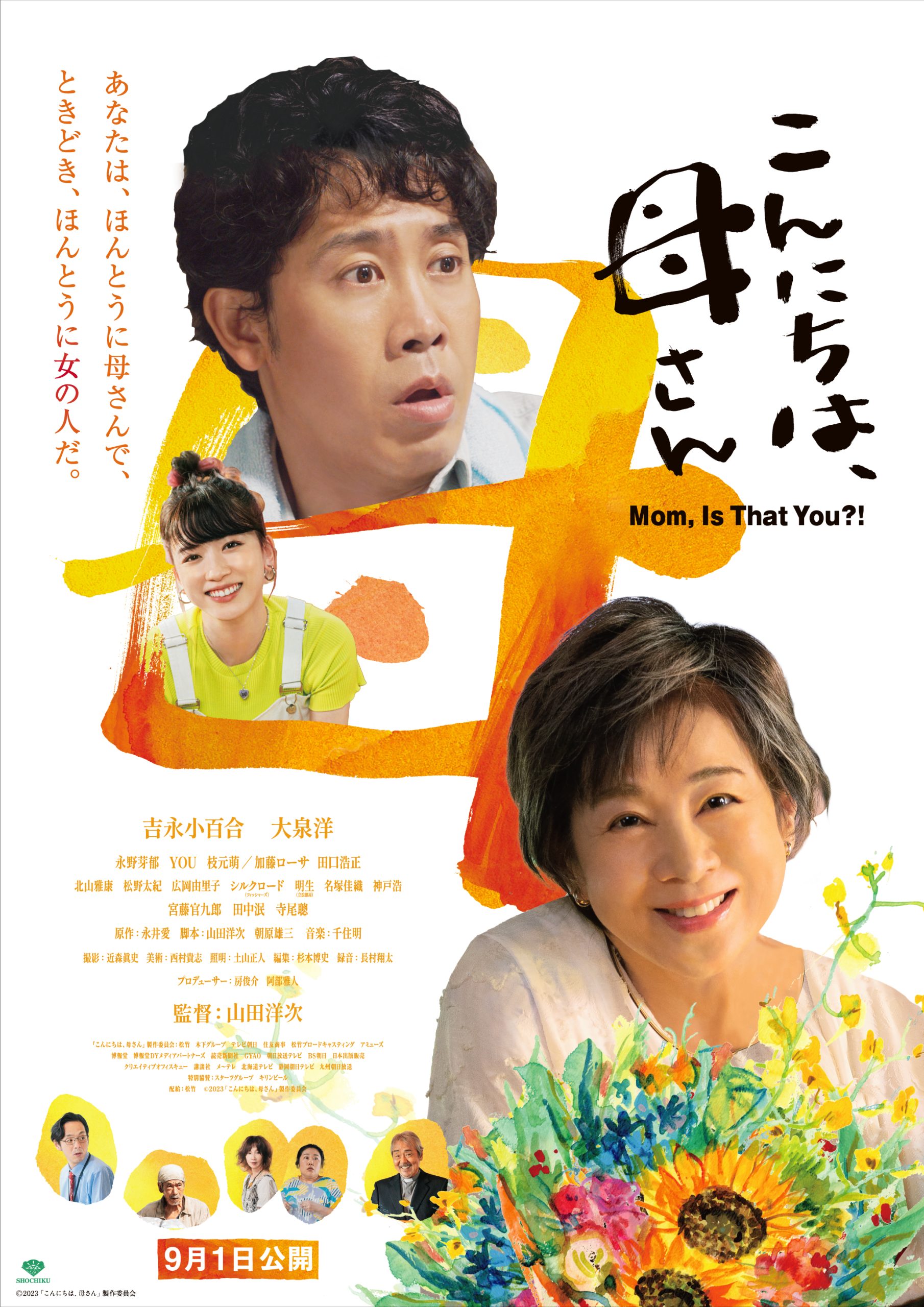

“People of my generation can’t throw anything away,” an older woman admits on her hearing her daughter-in-law has just been featured in a TV series about decluttering. Inspired by Ai Nagai’s 2001 play, the latest from veteran director Yoji Yamada Mom, Is that You? (こんにちは、母さん, Konichiwa, Okasan) seems to hint at a series of circular generational divides while suggesting that the children of the Bubble-era in particular are too quick to get rid of things they don’t think they don’t need anymore.

That’s the irony of soon-to-be 50-year-old Akio’s (Yo Oizumi) salaryman job in HR. It’s his job to cut dead wood from the company and this current round of polite requests to employees of a certain level to take early retirement includes his uni friend Kibe (Kankuro Kudo) who doesn’t take kindly to what he sees as a personal betrayal. Unlike Akio who is beginning to tire of the salaryman dream, Kibe fiercely fights for his position and identity as an executive at a big company even when faced with banishment room treatment and disciplinary dismissal after an altercation with the boss.

But what Kibe doesn’t know is that Akio is already facing a series of crises. His marriage has collapsed and his university student daughter Mai (Mei Nagano) is having a crisis of her own. Fresh from her tidying success, her mother has told her that all she can do is get good grades followed by a boring salaryman job like her dad’s which doesn’t seem to be what she wants which is why she’s run off to stay with her grandmother Fukue (Sayuri Yoshinaga) who runs a traditional shop selling tabi socks near the Sumida River. Fukue has a kindly, laid-back attitude remiscent of the shitamachi spirit found in other Yamada films in contrast to the stressed out uptightness of Akio who hasn’t told her about his impending divorce nor work troubles but finds himself paying a visit home in an attempt to sort himself out only to find Fukue keeping herself busy with a local charity group and nascent relationship with a church pastor.

Fukue’s charity work is emblematic of a waste not want not philosophy that has otherwise disappeared from the modern society as they pick up the things other people don’t want and donate them to the needy even if it sometimes seems a little simplistic or patronising. Biting into some reject crackers from the local rice cracker shop, Akio reflects that they’re something that’s made to console people and it’s work that has meaning unlike his soulless corporate job that gives him nothing other than stress and money. At the time the play was written, the fallacy of the salaryman dream was clear for all to see in the post-Bubble society but to a man like Akio getting a company job was a big deal and his success is still the talk of his mother’s friends even he starts to wonder if he still has time to start again and discover a more meaningful way of living.

Some of these ideas, and the timescales involved, make much more sense for the play’s millennial setting rather than the film’s apparent present day given the references to the firebombing of Tokyo which would require the older protagonists to be their late 80s to even remember. Akio dismisses his mother’s charity work and insists that the homeless are only those who opted out of the competitive society he too has come to doubt or else were excluded from it, while he’s resentful of her attachment to the pastor in contrast to Mai who is excited by the prospect of her grandmother’s love affair and enduring possibilities of age while Fukue is beginning to fear not death but dependency if her health should suddenly decline.

It’s in the midst of her heartbreak that the film affords Fukue a new beginning if in coming full circle, Akio choosing to make a clean break with the unhappiness in his life and Mai embracing her youth while falling for the old world charms of her grandmother’s tabi sock shop almost exclusively catering to sumo wrestlers, who as someone points out never waste anything, and people trying ceremony for the first time at 60. Like most of Yamada’s work, the film has a gentle humanity and melancholy poignancy but also a sense of hope and continuity that run contrary to an overly corporatised society in which young and old are already losing faith.

Mom, Is That You?! screened as part of this year’s Toronto Japanese Film Festival.

Original trailer (No subitles)