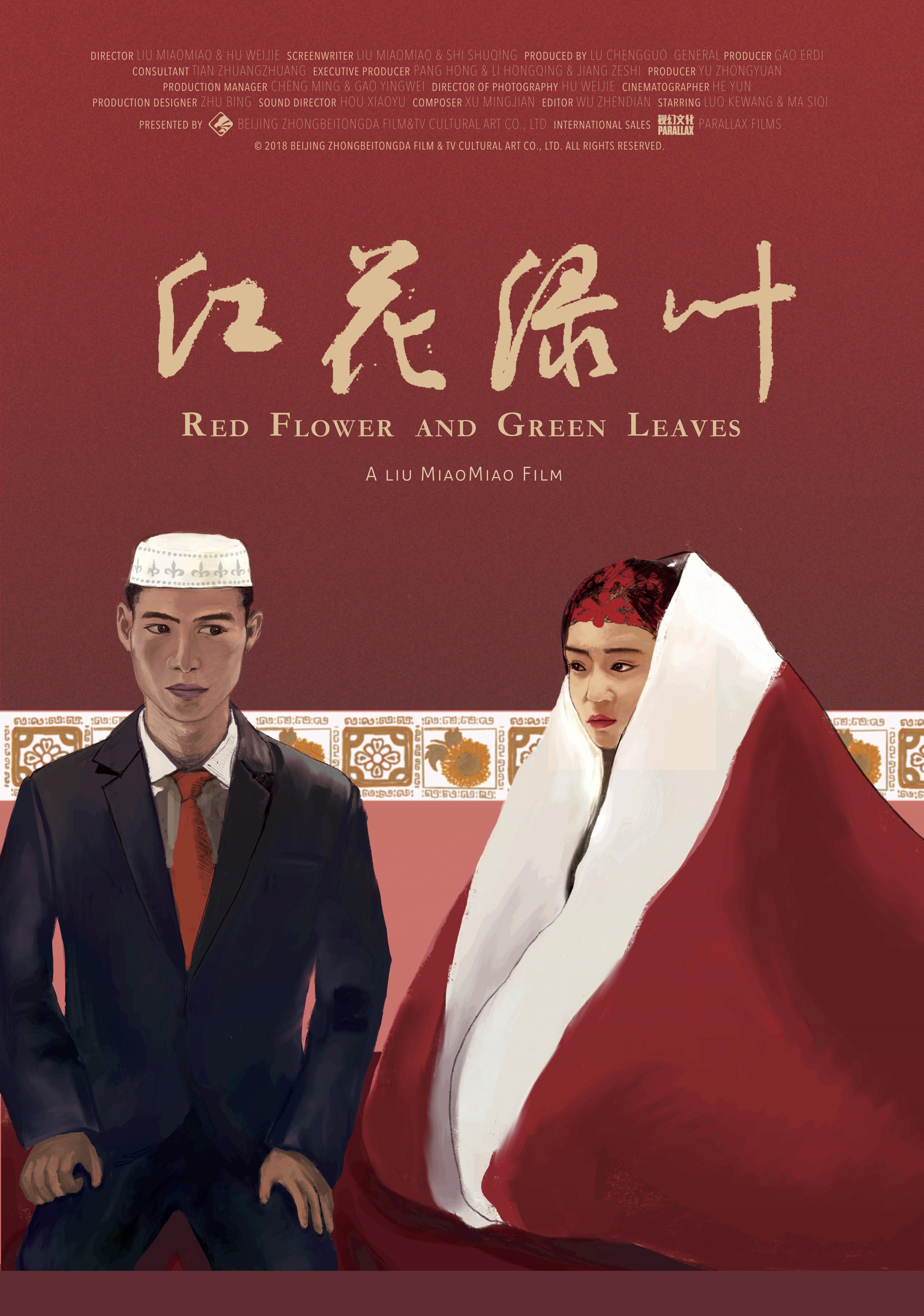

“They do things their way. We do ours our way” according to the rapidly maturing young husband at the centre of Liu Miaomiao & Hu Weijie’s touching marital romance, Red Flowers and Green Leaves (红花绿叶, hónghuā lǜyè). Shining a light on the under-explored culture of the Hui Muslim minority in China’s northwest, Liu and Hu’s heartfelt drama has some questions to ask about the potentially destructive effects of traditional culture, but ultimately allows its young couple to discover their own kind of happiness as they learn to understand each other while embracing their own senses of natural goodness.

The hero, Gubo, was diagnosed with a mysterious illness, apparently similar to epilepsy, some time in childhood, and has been written off by those around him ever since. Because of a deep sense of shame and inadequacy stemming from his condition which threatens but does not often interfere with the quality of his everyday life, he has long convinced himself that he will never marry or be very much of anything at all because he has “nothing to offer”. His well-meaning mother keeps trying to marry him off, but Gubo is convinced she does it to assuage her feelings of guilt in blaming herself for his illness (he does not blame her, but does harbour resentment towards the village’s irritating doctor, Li Feng). In a surprise development, Gubo’s aunt appears to have found the ideal match in an improbably beautiful young woman, Asheeyen, but his mother remains uncertain that Gubo can be talked into it. A conversation between the two older women makes plain that the reason the beautiful Asheeyen has not yet married has something to do with an incident in her past which has made her unsuitable in the eyes of some for marriage. Though the older generation are aware, they decide that it’s better the youngsters do not know of the other’s “issues” and that they rush the marriage through as soon as possible to prevent it potentially breaking down.

Despite himself, Gubo is smitten and allows himself to be swept into marriage but their early relationship is indeed as awkward as one might expect. Gubo, a kind and sensitive person, is keen to stress that he means to put no pressure on the nervous Asheeyen who spends most of their wedding night crying, but the distance between the pair even as Asheeyen blends seamlessly into the household, arouses the suspicions of the nosy aunt whose gentle prodding (secretly removing the second duvet to force them to share) begins to have the desired effect. But the central problem remains that each remains ignorant of the other’s “secret” and worried what will happen when it is eventually revealed. For Gubo that occurs when he’s turned down for social support after being unfairly usurped by Doctor Li who swipes it for his own disabled wife by wielding his social status against the mild-mannered Gubo who’d rather not have to deal with him anyway.

Doctor Li does indeed seem to do more harm than good, even if Gubo’s father later dismisses everything he says as “bullshit” not to be taken seriously. Li feels Gubo blames him for his condition because of some treatment he gave him as a child, while Gubo appears to resent him for constantly harping on about the limitations of his illness which seem to be far exaggerated. Doctor Li doesn’t quite think people like Gubo should marry at all, let alone have children. Even Gubo’s haughty brother Shuerbu, preparing to enter the military academy, writes him off a useless idiot while intensely jealous of his beautiful wife. When the couple eventually conceive a child, Doctor Li goes so far as to suggest that it shouldn’t be born because Gubo’s condition may be hereditary and he finds it distasteful for him to have a child, while Shuerbu thinks it’s unfair because Gubo will not be able to look after it and the burden will fall disproportionately on Asheeyen.

Asheeyen, by contrast, is mildly ambivalent to her circumstances in view of the mysterious past but is also struck by Gubo’s goodness. Her sister-in-law, while openly criticising her brother as a husband, agrees that Gubo is a “decent” man, the criteria being a mix of the ability to provide material comfort with a genuine intention to care. Realising that they both have secrets the other was not aware of reawakens Gubo’s sense of inferiority, reminding him that they’ve been paired off together because they were each viewed as somehow “damaged”. Discovering Asheeyen’s past sends him into a petulant, depressive funk that threatens to ruin everything in a mistaken bout of destructive male pride, but eventually love wins out. Asheeyen and Gubo may have been railroaded into a traditionally arranged marriage not quite against their wills, but that doesn’t mean that they have to go on doing everything traditionally, taking their elders’ advice at face value and always falling victim to the unpleasant Doctor Li who reacts to Gubo’s grudging agreement to buy his scooter even though Doctor Li is always telling him he’s too disabled to ride one because Asheeyen could use it with a surprised “I suppose we even have women driving trains these days”. Coming together, the couple are resolved to do things in their own way and make their decisions together, no matter what the future might bring.

Trailer (English subtitles)

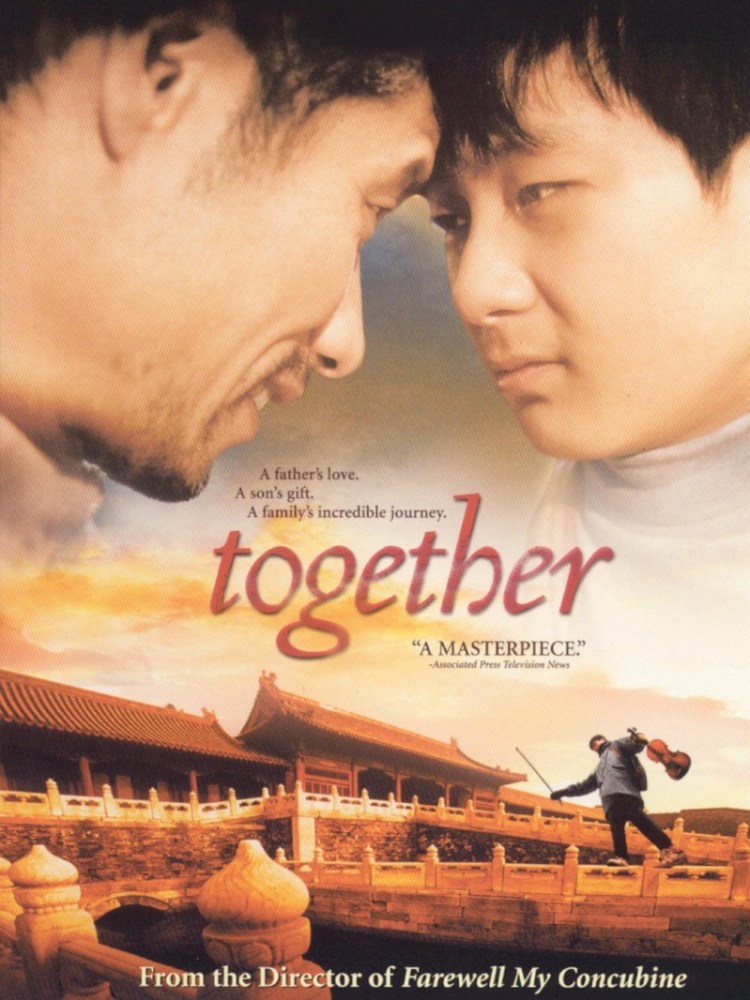

It’s a sad truth, but talent isn’t enough to see you succeed in the wider world. In fact, all having talent means is that unscrupulous people will seek to harness themselves to you in the hope of achieving the kind of success which they are incapable of obtaining for themselves. 13 year old Xiaochun is about a learn a series of difficult life lessons in Chen Kaige’s Together (和你在一起, Hé nǐ zài yīqǐ), not least of them what true fatherhood means and whether the pursuit of fame and fortune is worth sacrificing the very passion that brought you success in the first place.

It’s a sad truth, but talent isn’t enough to see you succeed in the wider world. In fact, all having talent means is that unscrupulous people will seek to harness themselves to you in the hope of achieving the kind of success which they are incapable of obtaining for themselves. 13 year old Xiaochun is about a learn a series of difficult life lessons in Chen Kaige’s Together (和你在一起, Hé nǐ zài yīqǐ), not least of them what true fatherhood means and whether the pursuit of fame and fortune is worth sacrificing the very passion that brought you success in the first place.