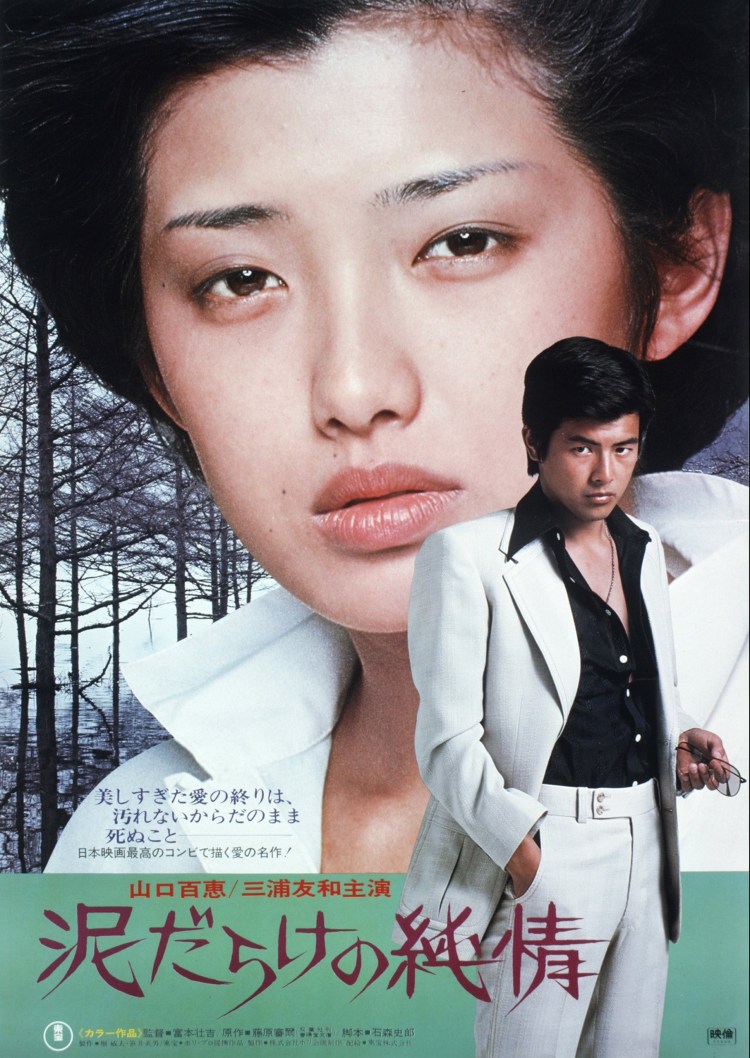

Japanese youth cinema was in a strange place by the late 1970s. Angsty seishun eiga had gone out with Nikkatsu’s move into Roman Porno and the artier, angry youth films coming out through ATG were probably not much for a teen audience. The Kadokawa idol movie was only a few years away but until then, films like Love in the Mud (泥だらけの純情, Dorodarake no Junjo) arrived to plug the gap. Based on a novella by Shinji Fujiwara which had been previously adapted by Ko Nakahira in 1963 in a version starring Sayuri Yoshinaga and Mitsuo Hamada, Love in the Mud is a classic tale of poor boy meets rich girl and ends in a predictably hopeless way but in deep contrast to the prevailing culture of the time, the film takes the “junjo” or “purity” in its title literally in its innocent chasteness.

Japanese youth cinema was in a strange place by the late 1970s. Angsty seishun eiga had gone out with Nikkatsu’s move into Roman Porno and the artier, angry youth films coming out through ATG were probably not much for a teen audience. The Kadokawa idol movie was only a few years away but until then, films like Love in the Mud (泥だらけの純情, Dorodarake no Junjo) arrived to plug the gap. Based on a novella by Shinji Fujiwara which had been previously adapted by Ko Nakahira in 1963 in a version starring Sayuri Yoshinaga and Mitsuo Hamada, Love in the Mud is a classic tale of poor boy meets rich girl and ends in a predictably hopeless way but in deep contrast to the prevailing culture of the time, the film takes the “junjo” or “purity” in its title literally in its innocent chasteness.

As the camera pans over a rapidly developing city, it settles on a bright red, flashy sports car being driven by Mami (Momoe Yamaguchi), the daughter of the Japanese Ambassador to Spain, with her friend sitting cheerfully in the passenger seat. Disaster strikes when the pair are run off the road by a biker gang who taunt them from outside the car, threatening rape and robbery. Luckily for them another gangster turns up, beats up the bad guys and saves the girls but alarm bells should have been ringing when he asks Mami to step out of the car and “thank him properly”. Mami, stupidly, does what she’s told and the girls are hijacked by gangsters round two. When they reach the shady place the gangsters are planning to have their wicked way with them, a third wave of gangster appears, disapproves of the goon’s intentions and heroically fights them off. However, the girls’ saviour is stabbed in the stomach and then later stabs and kills the leader of the aggressors.

The noble gangster, Jiro (Tomokazu Miura), tells the girls to run – which they do, but somehow Mami can’t quite bring herself leave him. A thoroughly middle-class girl, Mami is at university studying English literature but her dream is to open a hat shop in Paris and she spends most of her spare time working with a hat designer. In the absence of her father, Mami’s uncle (Ko Nishimura) has been looking after her but is the classic upperclass male who thinks the hat stuff is just a hobby and what Mami needs is a good husband as soon as possible. Accordingly he’s set her up with a pleasant enough business contact he hopes will both support Mami in the manner to which she’s been accustomed and his business dealings too.

Your average teenage girl might not be in such an extreme situation as young Mami, but most can certainly sympathise with her lack of agency. The life her uncle has planned for her is not what she wants but more than that, she’s acutely aware of being denied a choice in her future. She may be rich, but she’s never been free. Jiro, by contrast, grew up poor in tragic family circumstances and enjoys his own kind of freedom even if he feels himself constrained by his social class and lack of opportunities following a life in care with no real education. Not actually a yakuza but a gambler and petty punk living on the fringes of the underworld, Jiro has been content to live a meaningless life of empty gains but as his rescuing of Mami and her friend shows, he has a kind heart which extends to delivering presents to the daughter of a melancholy bar hostess currently living in an orphanage.

Jiro’s nobility is of a true and pure kind. After Mami comes forward to testify in Jiro’s defence, she tries to strike up a friendship but Jiro rebuffs her. He’s too smart not to know posh girl and poor boy never ends well, but then they do have a real connection which proves hard to kill. Their social differences are made apparent when Mami makes the naive decision to invite Jiro to a party at her fancy mansion. He buys a nice suit and an expensive necklace as a present, but Mami’s nanny doesn’t want to let him in and when Mami introduces Jiro to her uncle he whips out a checkbook causing Jiro to leave enraged. Nevertheless Mami chases Jiro through the shadier parts of Shinjuku, taking her first taste of gyoza, frequenting underground nightclubs and mahjong parlours, and swapping her elegant outfits for the casual jeans and T-shirts of Jiro’s world.

While all of this is going on, Jiro is also embroiled in the gang trouble which started with the stabbing in the beginning. A “friend”, almost, of the local policeman, it’s not surprising suspicion falls on Jiro and he faces a bleak future if he chooses to remain in Shinjuku. The courtship of the pair is a stuttering, nervous affair in which the emboldened Mami chases Jiro whose sense of honour teaches him to try and avoid her all the while he too is smitten. This is, however, a chaste and innocent love. Jiro and Mami spend a night together gazing at the moon but all they do is talk and the climax of the romance is met firstly with an innocent hug, and then a troubling slap from Jiro which is designed to show the depth his love in his desire to push Mami away, rather than anything more explicit.

A tragic tale of love across the class divide, Love in the Mud indulges the worst aspects of its genre in the fetishisation of doomed romance and extreme dedication the idea of “pure” emotion. The force that keeps Jiro and Mami apart, rather than entrenched social mores and differing forms of oppression is a kind of fatalistic pessimism which says the only true love is death. Perhaps too innocent and too chaste, Love in the Mud never earns its melodramatic ending but does what it needs to in appealing to its teenage target audience, neatly anticipating the genial edginess of the idol movie but failing to move much beyond capturing its moment as a snapshot of late ’70s youth culture.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

1 comment