For various reasons, external commentators on Japanese culture have long held the view that the idea of “death” takes on a much more central position in the lives of ordinary people than it might elsewhere. Death is, however, as much of a taboo in Japan as it is elsewhere – few want to talk about the process of death and dying, of illness and of caring for the sick. Perhaps as a way to evade this particular paradox, there is another tradition in which those aware of their own impending death write a kind of letter for those they will leave behind. Like a testament which accompanies a will, the “isho” can include biographical details, confessions, advice and apologies by way of a final word of parting and a demonstration of having accepted one’s death.

For various reasons, external commentators on Japanese culture have long held the view that the idea of “death” takes on a much more central position in the lives of ordinary people than it might elsewhere. Death is, however, as much of a taboo in Japan as it is elsewhere – few want to talk about the process of death and dying, of illness and of caring for the sick. Perhaps as a way to evade this particular paradox, there is another tradition in which those aware of their own impending death write a kind of letter for those they will leave behind. Like a testament which accompanies a will, the “isho” can include biographical details, confessions, advice and apologies by way of a final word of parting and a demonstration of having accepted one’s death.

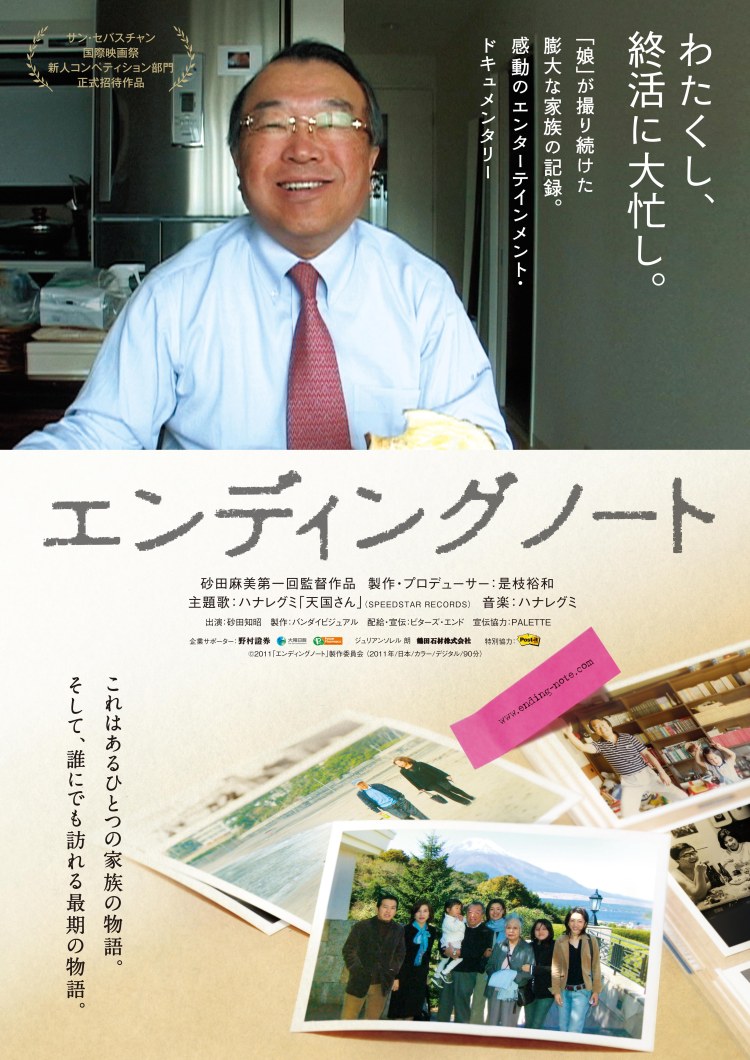

This concept is what inspires the subject of Mami Sunada’s documentary, Death of a Japanese Salesman (エンディングノート, Ending Note), in his desire to create an “Ending Note” when diagnosed with terminal stomach cancer shortly after retiring from a lifetime spent as a regular salaryman. Tomoaki Sunada’s “Ending Note” is intended to be something warmer than an isho and completely divorced from any legal concept but nevertheless a kind of letter saying the things it was too hard to say out loud.

Sunada captures her father’s last days with equal parts affection and detachment. Tomoaki is a humorous man whose wide grin and dry wit help to alleviate what is an unavoidably heavy subject as he comes to terms with the aggressive nature of his illness. The thing is, Tomoaki never gets round to writing that “Ending Note” because he’s just too busy living to think about dying. What he writes is a kind of bucket list which runs from typically practical concerns such as looking at venues in which his funeral might be held and talking over converting to Christianity, to definitively patching things up with his wife and getting to see his three grandchildren again who live abroad in America because of his son’s job.

Living in America Tomoaki’s son perhaps has things a little easier than his father did (even if he’s inherited Tomoaki’s notorious attention to detail and meticulous planning). As Tomoaki puts it in one of Sunada’s flashback moments, middle-aged men like him built the modern Japan. Exclaiming “The company is life!”, albeit with an ironic smile on his face he leaves for work just as he did every morning for over forty years at the same company and for most of it in marketing and sales. The traditional Japanese family demanded a strict division of labour with men pouring their efforts and emotions into their careers and women, supposedly, subsuming their hopes and desires into creating a happy family home. During their working lives, therefore, men like Tomoaki rarely got to see the families they were working to support, placing undue burdens on their wives and appearing as little more than absent disciplinarians to their children. Retirement offers an opportunity to finally become a part of family life, enjoying the days out and long lunches often so impossible for a company man, but Tomoaki has been robbed of the right to enjoy his old age by a cancer diagnosis received almost immediately after the end of his career.

Sunada in effect writes her father’s Ending Note for him, both through the film and the voice over narration she herself delivers written in her father’s playfully ironic authorial voice. Taking cheeky potshots at herself as the “accidental” youngest child whose still unmarried state apparently weighs on her dying father’s mind, Sunada adds both bite and warmth to her “father’s” final words as he waxes philosophical on death and the afterlife while trying to plan pragmatically for his own eventual end. The whimsical indie score also lends to the lightness of the exercise but Sunada does not shy away from the rapidity of her father’s decline or cruelty of his illness, taking her camera away only at the moment of death. Raw and painful, Sunada’s fearsome exploration of the process of dying is one of ordinary tragedy but also becomes a glorious celebration of life from all of its sadness and difficulties to shared laughter and the joy of new arrivals.

Screened as part of Archipelago: Exploring the Landscape of Contemporary Japanese Women Filmmakers.

Original trailer (no subtitles)