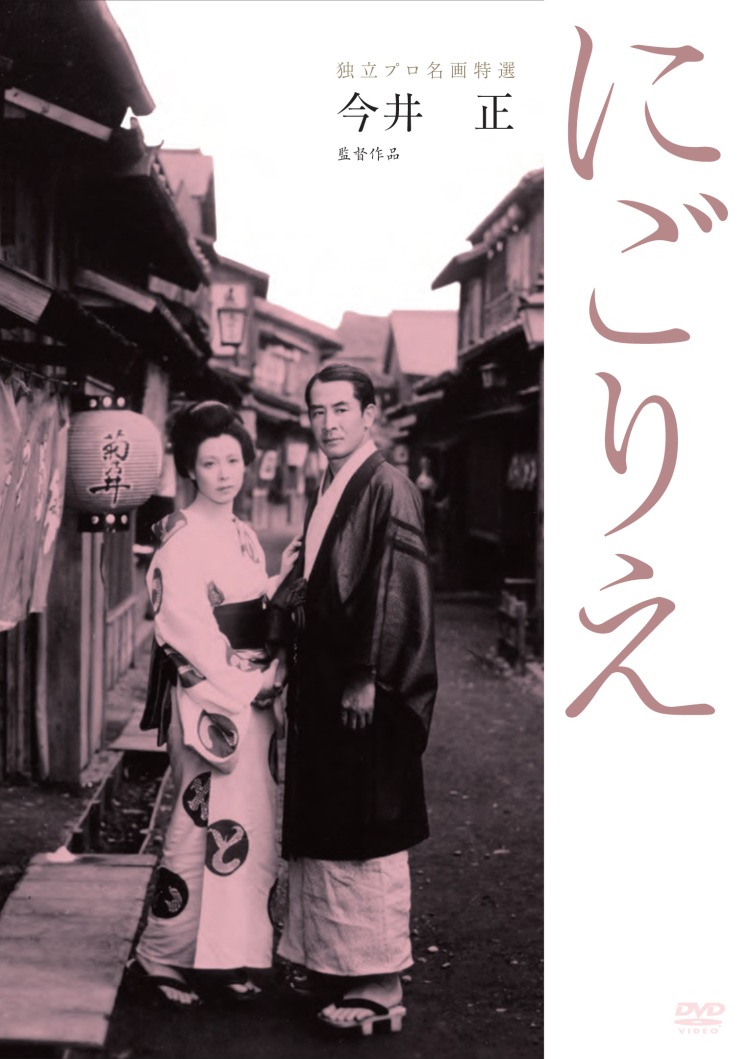

Tadashi Imai was among the greatest directors of the golden age though his name remains far less known than contemporaries Ozu or Mizoguchi. Despite beginning in outright propaganda films during the war, Imai is best remembered as a staunchly left wing director whose films are known for their gritty realism and opposition to oppressive social codes. An Inlet of Muddy Water (にごりえ, Nigorie) very much fits this bill in adapting three stories from Japanese author Ichiyo Higuchi. Higuchi is herself a giant figure of Japanese literature though little of her work has been translated into English. Like Imai’s films, Higuchi’s stories are known for their focus on female suffering and the prevailing social oppression of the late Meiji era which had seen many changes but not all for the better. Higuchi was not a political writer and her work does not attack an uncaring society so much as describe it accurately though her own early death from tuberculosis at only 24 certainly lends weight to the tragedy of her times.

Tadashi Imai was among the greatest directors of the golden age though his name remains far less known than contemporaries Ozu or Mizoguchi. Despite beginning in outright propaganda films during the war, Imai is best remembered as a staunchly left wing director whose films are known for their gritty realism and opposition to oppressive social codes. An Inlet of Muddy Water (にごりえ, Nigorie) very much fits this bill in adapting three stories from Japanese author Ichiyo Higuchi. Higuchi is herself a giant figure of Japanese literature though little of her work has been translated into English. Like Imai’s films, Higuchi’s stories are known for their focus on female suffering and the prevailing social oppression of the late Meiji era which had seen many changes but not all for the better. Higuchi was not a political writer and her work does not attack an uncaring society so much as describe it accurately though her own early death from tuberculosis at only 24 certainly lends weight to the tragedy of her times.

In the first part of the film which is inspired by one of Higuchi’s best known stories, The Thirteenth Night, a young woman returns home to her parents, no longer able to bear living with an emotionally abusive husband. Oseki (Yatsuko Tanami) had been raised an ordinary, lower middle-class girl but, like many a heroine of feudal era literature, caught the eye of a prominent nobleman who determined to marry her despite their class difference. Life is not a fairytale, and so the nobleman quickly tired of his beautiful peasant wife, belittling her lowly status, lack of education, and failure to slot into the elite world he inhabits.

Oseki’s plight elicits ambivalent reactions in each of her parents though they both sympathise with her immensely, if in different ways. Her mother (Akiko Tamura) is heartbroken – having long believed her daughter to be living a blissful life of luxury, she feels terribly guilty not to have known she had been suffering all this time and believes Oseki has done the right thing in leaving. Her father (Ken Mitsuda), however, also feels sad but reacts in practicality, pointing out that to leave her husband now would mean losing her son forever and probably a long, lonely life of penury. He, somewhat coldly, tells her to go back, grin and bear it. Oseki can see his point and considers resigning herself to return if only to look after her son.

On her way home she runs into a childhood friend whom she might have married if things had not turned out the way they did. “Life gets in the way of the things we want to do”, she tells him by of explanation for not staying in touch. Rokunosuke (Hiroshi Akutagawa), once a fine merchant, is now a ragged rickshaw driver, bereaved father, and divorcee. Like Oseki his life is a tragedy of frustration with the added irritant that he and Oseki might have been happy together, rather than independently miserable, if an elite had not suddenly decided to interfere by crossing class lines just because he can rather than out of any genuine feeling.

The callousness of elites is also a theme in the second story, The Last Day of the Year, in which a young maid, Omine (Yoshiko Kuga), works for a wealthy household dominated by a moody, penny pinching mistress whose mistreatment of her staff is more indifference than deliberate scorn. Omine’s uncle, who raised her, has fallen ill. At the beginning of his illness he took out a loan but he’s got no better and still needs to pay it back so he asks Omine to ask the mistress for an advance of the paltry sum of two yen in the hope that his son will be able to enjoy a new year mochi like the other kids. The mistress says yes and then changes her mind, leaving Omine to consider a transgressive act of social justice.

Where The Thirteenth Night and The Last Day of the Year pointed the finger at uncaring elites, Troubled Waters broadens its disdain to the entire world of men in focussing on two women caught on either side of the red light district – Oriki (Chikage Awashima), a geisha stalked by a ruined client, and the client’s wife, Ohatsu (Haruko Sugimura), who endures a life of penury thanks to her husband’s geisha obsession. Oriki’s sad story is recounted to a wealthy patron (So Yamamura) who is more fascinated in learning the secrets of her soul than her kimono, but like many of her age it begins with parental strife, orphanhood and perpetual imprisonment as a geisha wondering what will become of her when her looks fade and she’s no longer number one. She has no control over the men who spend time with her but is worried by Gen (Seiji Miyaguchi) who ruined himself buying her time and now stalks her in and around the inn. Infatuated and obsessed with Oriki, Gen has turned against his noble wife Ohatsu who is working herself to the bone to support the family while Gen has resorted to a life of casual labour but rarely does much of anything at all.

Recalling Higuchi’s famous diary, Imai opens each of the segments with a brief voiceover detailing the inconsequential details of the weather with a world weary, often melancholy tone as the writer laments too much time spent on fiction and resolves to tell the story of the world as it really is. There is no real connection or overarching theme which unites the three stories, save for the continued suffering of women at the hands of men and the society they have devised. Oseki must return to her abusive husband, Omine will continue to work for her heartless mistress, and Ohatsu will have to make do on her own after being so thoroughly let down by her husband. There is no recourse or escape, no path forward that will allow the women to break free of their oppression or even to learn to be free within it. Each of the stories is bleak, ending on a note of resignation and acceptance of one’s fate as terrible as that may be but Imai’s ending is most terrible of all, reminding us that today is simply another day and the heavy atmosphere of dread and oppression is certain to endure as long as we all remain resigned.

Screened at BFI as part of the Women in Japanese Melodrama season.

1 comment