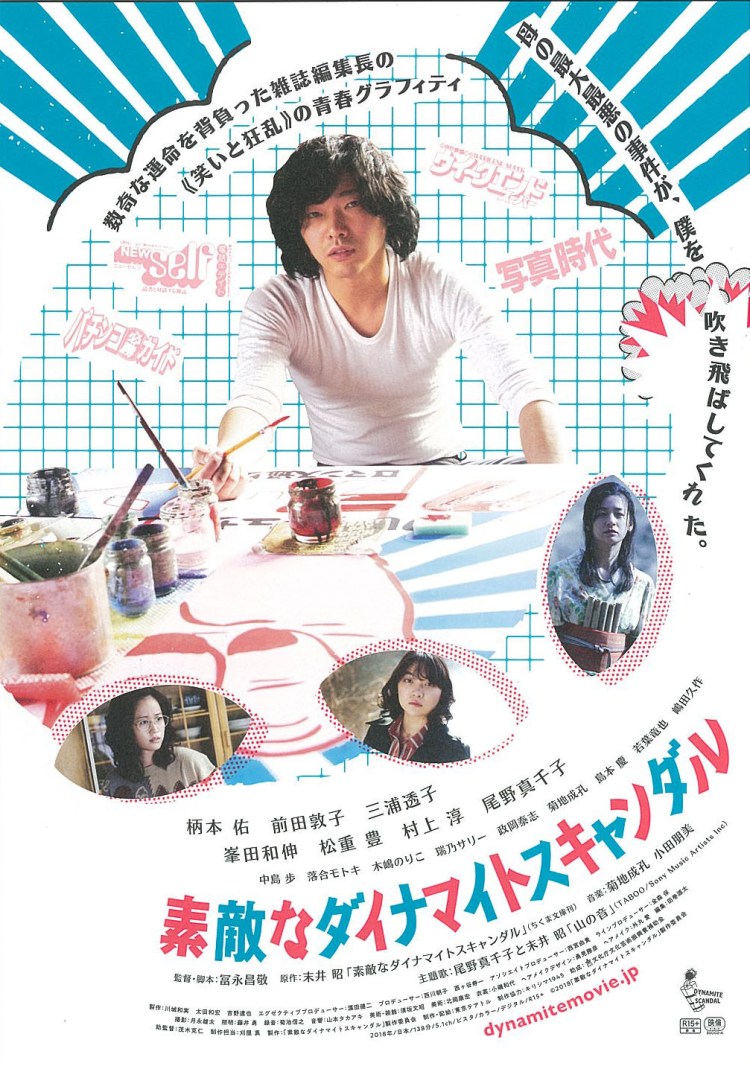

The division between “art” and “porn” is as fuzzy as the modesty fog which still occasionally finds itself masking “obscene” images in Japanese cinema, but for accidental king of the skin rag trade Akira Suei it’s question he finds himself increasingly unwilling to answer even while he employs it to his own benefit. Back in the heady pre-internet days of the 1980s, Suei was the public face behind a series of magazines along differing themes but which all included “artistic” images of underdressed women in provocative poses alongside more “serious” content provided by such esteemed figures as Daido Moriyama and Nobuyoshi Araki in addition to stories and essays penned by “legitimate” authors and the more scurrilous fare written by Suei himself. Inspired by one of Suei’s essays “Dynamite Graffiti” (素敵なダイナマイトスキャンダル, Sutekina Dynamite Scandal), Masanori Tominaga’s ramshackle biopic has the informal feel of a man telling his sad life story to a less than attentive bar girl as he takes us on a long, strange walk through the back alleys of ‘70s Japan.

The division between “art” and “porn” is as fuzzy as the modesty fog which still occasionally finds itself masking “obscene” images in Japanese cinema, but for accidental king of the skin rag trade Akira Suei it’s question he finds himself increasingly unwilling to answer even while he employs it to his own benefit. Back in the heady pre-internet days of the 1980s, Suei was the public face behind a series of magazines along differing themes but which all included “artistic” images of underdressed women in provocative poses alongside more “serious” content provided by such esteemed figures as Daido Moriyama and Nobuyoshi Araki in addition to stories and essays penned by “legitimate” authors and the more scurrilous fare written by Suei himself. Inspired by one of Suei’s essays “Dynamite Graffiti” (素敵なダイナマイトスキャンダル, Sutekina Dynamite Scandal), Masanori Tominaga’s ramshackle biopic has the informal feel of a man telling his sad life story to a less than attentive bar girl as he takes us on a long, strange walk through the back alleys of ‘70s Japan.

The entirety of Suei’s (Tasuku Emoto) life is lived in the wake of a bizarre childhood incident in which his mother (Machiko Ono), suffering with TB and trapped in an unhappy marriage to a violent drunk, chose to commit double suicide with the young man from next door. Perhaps there’s nothing so strange about that in the straightened Japan of 1955, but Suei’s mother chose to end her life in the most explosive of ways – with dynamite stolen from the local mine. Carrying the legacy of abandonment as well as mild embarrassment as to the means of his mother’s dramatic exit, Suei finds himself a perpetual outsider drifting along without the need to feel bound by conventional social moralities as symbolised by the “ideal” family.

What he longs for, by contrast is freedom and independence. Bored by country life he dreamt of moving to the city to work in a factory, but the problem with factories is that they’re mechanical and turn their employees into mere tools with no possibility of personal expression or fulfilment. Spotting an advert for courses in “graphic design”, Suei’s world begins to open up as he embraces the bold new possibilities of art even as it wilfully intersects with commerce.

Taken with the new philosophy of design as the message, a means of “exposing” oneself and ultimately enabling true human connection, Suei remains frustrated by the limitations of his role as a draughtsman for local advertisers and, inspired by a friend’s beautiful poster, finds himself entering the relatively freer creative world of the “cabaret” scene as a crafter of signboards and flyers. The cabaret bars are little better than the factories, exploiting the labour of women who themselves are the product, but Suei’s distaste is soon worn down by constant exposure. From the clubs and cabarets it’s only a natural step towards erotic artwork, nudie photographs, and finally a vast magazine empire of “literary” pornography.

Suei’s accounts of his youth are filled with a lot of high talk about the possibilities of art, of his desire to remove the masks which keep us divided so that we might all know “true” human love. Whether his adventures in adult magazines can be said to do that is very much up for debate. They are, as he freely admits, expressions of male fantasy – exposing a perhaps unwelcome truth about the relationships between men and women even as they continue to exploit them. Yet Suei’s own desire to find something more than a potential for titillation in his work continues to dwindle as he finds himself engaged in increasingly complicated schemes to avoid censure from the police while simultaneously insisting that his magazines are both “artistic” and not.

His insistence that the photographs are “artistic” becomes his primary weapon in getting sometimes vulnerable young women to agree to take their clothes off. Abandoning his loftier aspirations, Suei sinks still further into the smutty morass whilst still maintaining the pretension that his magazines are not like the others. He neglects his wife (Atsuko Maeda) to chase fleeting affections with unsuitable or unstable women, one of whom eventually descends into a mental breakdown which provokes in him only the realisation that his desire for her was a romantic fantasy which her illness has now dissipated. Art is an explosion, Suei claims, but his mother was the explosive force in his life, blowing him off course and leaving him too wounded to embrace the reality he so desperately claims to crave but continues to reject in favour of the same kind of male fantasies his magazines peddle.

Everyone around Suei seems to be damaged. Nary a face in the red light district is without a bandage or bruise of some sort. These are people who’ve found themselves at the bottom of the ladder and are desperately trying to scrap their way up. Times change and Suei’s empire implodes. Porn is swapped for pachinko as the exploitable pleasure of choice paving the way for yet another reinvention which sees him throw on a kimono to rebrand himself as his own mother and self-styled pachinko expert. You couldn’t make it up. Still, perhaps there is something more honest in Suei’s pachinko persona than it might first appear even if his present “art” is unlikely to enlighten us to the true nature of love.

Dynamite Graffiti is screening as the opening night movie of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

“He neglects his wife (Atsuko Maeda)” There is something VERY wrong with this sentence… 😉 😛

Exactly. What was he thinking?!

I know. It’s up there with Ray Milland wanting to kill Grace Kelly in Dial M for Murder. I mean, seriously? 😮