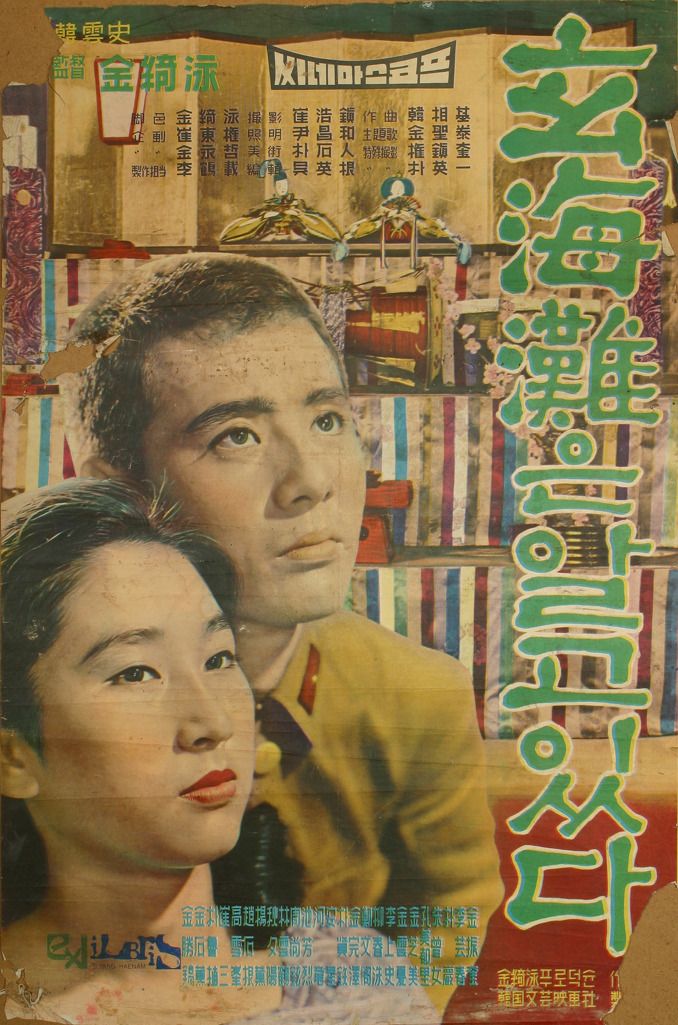

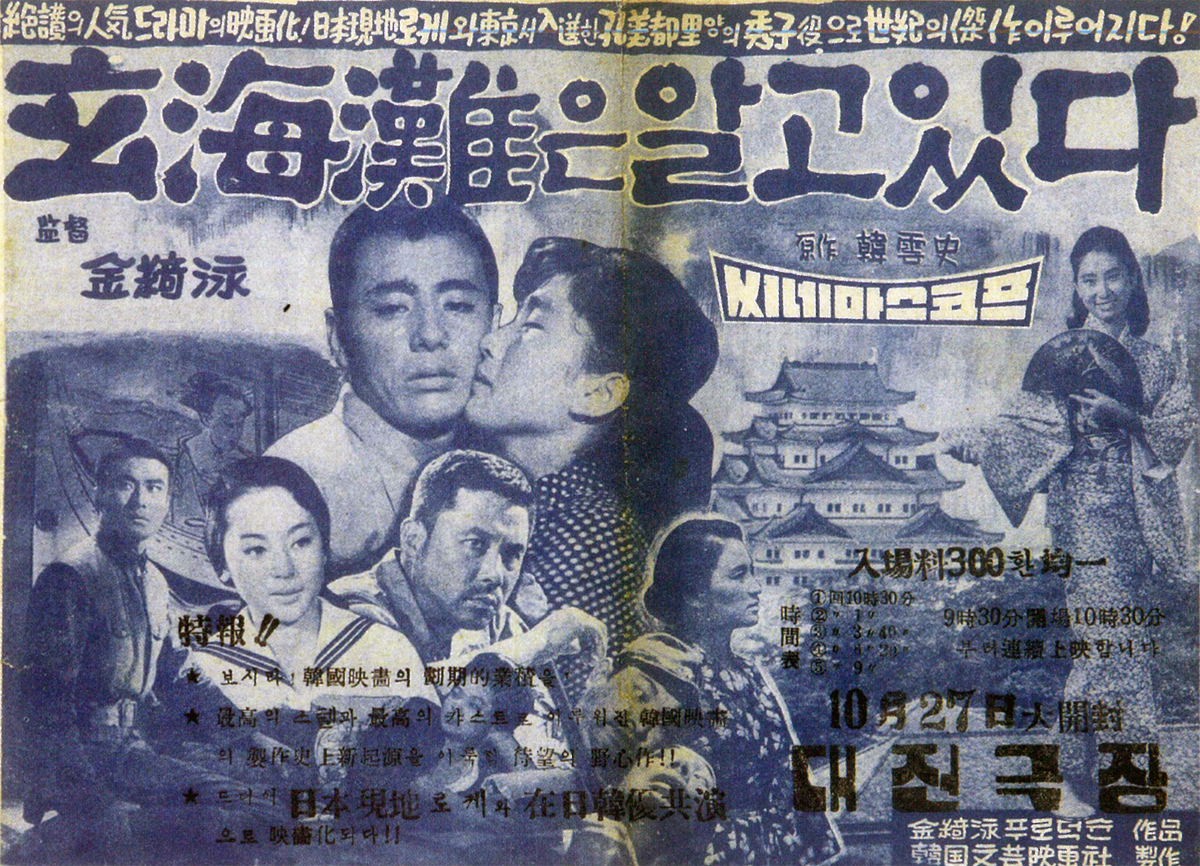

The Korea of 1961 was a land in flux. The corrupt regime of Rhee Syngman had been brought to its knees following mass protests regarding the rigged 1960 elections but hopes for a new democracy were cut short when military General Park Chung-hee staged a coup, later declaring himself president for life and continuing his authoritarian rule until he was assassinated by one of his own subordinates. Kim Ki-young’s The Sea Knows (玄海灘은 알고 있다 / 현해탄은 알고 있다, Hyeonhaetaneun Algoitta) arrived perhaps at just the right time, ducking under the radar before the Motion Picture Law of 1962 would forever change the industry and if not prevent at least frustrate any attempt to discuss the controversial themes at the heart of Kim’s drama. The Sea Knows is, like much of Kim’s work, a tale of power and desire only this time on a wider scale as he examines the complicated relationship between Korea and Japan as mediated through romantic melodrama.

The Korea of 1961 was a land in flux. The corrupt regime of Rhee Syngman had been brought to its knees following mass protests regarding the rigged 1960 elections but hopes for a new democracy were cut short when military General Park Chung-hee staged a coup, later declaring himself president for life and continuing his authoritarian rule until he was assassinated by one of his own subordinates. Kim Ki-young’s The Sea Knows (玄海灘은 알고 있다 / 현해탄은 알고 있다, Hyeonhaetaneun Algoitta) arrived perhaps at just the right time, ducking under the radar before the Motion Picture Law of 1962 would forever change the industry and if not prevent at least frustrate any attempt to discuss the controversial themes at the heart of Kim’s drama. The Sea Knows is, like much of Kim’s work, a tale of power and desire only this time on a wider scale as he examines the complicated relationship between Korea and Japan as mediated through romantic melodrama.

We open in 1944. Korean student Aro-un (Kim Wun-ha) has been conscripted into the Japanese army following an incident in which he embarrassed a high-ranking official (something which has made him a local hero at home). Despite the fact that Korea has been inducted into the Japanese empire and Koreans are now sons of the emperor too, the regular Japanese troops are not exactly grateful for service of their brethren from across the sea. Koreans are a pain, they decry. They’re always going on about justice and fairness. They won’t just shut up and take their lumps like regular Japanese soldiers. The “50 year tradition” of the Japanese army is to break the will of new recruits through violence, strip them of their individuality, and reduce them to a finely tuned hive mind.

Needless to say, Aro-un is not eager to comply. There’s a strong strain of homoeroticism in the strangely camp banter between the higher-ups. At the first inspection the commanding officer takes a good look at Aro-un, decides he resembles a “cute puppy” and recommends he come to his room to get some “biscuits”. Meanwhile a particularly sadistic NCO, Mori (Lee Ye-chun), pinches the chest of Aro-run’s judo champion friend Inoue (Lee Sang-sa) and decides he’ll not be an easy target – unlike the short and wiry Aro-un who is too righteous to know what’s good for him. Mori, an insecure and under qualified NCO, makes use of men like Aro-un to entrench his own position through the “50 year tradition” of military discipline. The humiliations mount until Aro-un is forced to lick Mori’s excrement encrusted boots in punishment for having failed to polish them to his satisfaction.

Yet, unlike in the majority of Korean films dealing with war and occupation, the Japanese are not universally bad – there are many just like Aro-un who are uncomfortable with the militarist line and are doing what they can to resist, albeit often passively. Aro-un’s university friend, Nakamura (Kim Jin-kyu), is just such a man, turning down the possibilities of promotion to avoid endorsing the regime while acknowledging that there is little more he can do to free himself from it. It’s through Nakamura that Aro-un meets his own source of salvation in the unlikely figure of a young Japanese woman – Nakamura’s sister Hideko (Gong Midori). Hideko originally betrays the common prejudice against Koreans in claiming that the perpetrators of a nearby robbery were most likely Korean seeing as Koreans can’t get jobs and therefore have no other options than to steal, though in retrospect perhaps her assertions were a more logical comment on poverty and entrenched oppression than they were on racial stereotyping.

Hideko is, as Aro-un later points out, a very unusual Japanese woman. A free spirit, she finds herself drawn to Aro-un and is committed to pursuing a course of true feeling over that laid down by the codes of her society, choosing his sensitivity over the brutalisation of her militarist nation. War, Aro-un muses philosophically, is about the manipulation of the present. Love is about the foundation of a future. Yet there is also something dark and imbalanced even in their otherwise pure romance as each finds themselves becoming a symbol of suffering and violence. Aro-un is drawn to Hideko’s unexpected warmth as she sheds tears for his suffering on hearing of his various degradations, seeing no difference in the tears of a Japanese woman and those of his Korean mother who each felt his pain as their own, but Hideko’s insistence on hearing of his latest humiliations almost takes on a sadistic quality as the pair become bound by suffering as much as by innocent connection.

Kim’s central tenet is a bold one for the increasingly volatile world of 1961, making a case for borderless connection over nationalistic chest thumping and championing the resilience of the human spirit as well as the enduring power of love as a counter to the horrors of war. War is, in another of Aro-un’s philosophical musings, just something that happens to you and makes enemies of those who might have been friends. Making extensive use of stock footage and model shots, Kim plunges Aro-un into a fiery hell from which only love and will can save him. An unexpectedly nuanced but no less harrowing tale of wartime brutalisation and spiritual resistance, The Sea Knows is an impassioned plea for humanity in an inhumane age in which there are no heroes and no villains, only victims and resistors caught in a vast web of power and madness.

The Sea Knows was screened as part of the Korean Cultural Centre’s Korean Film Nights 2018: Rebels with a Cause series. You can also watch it online for free courtesy of the Korean Film Archive’s YouTube channel. The existing print is, however, incomplete and badly damaged – four sequences in which there is picture but no sound or sound but no picture are missing / unsubtitled in the online version but are present in the restoration.

1 comment