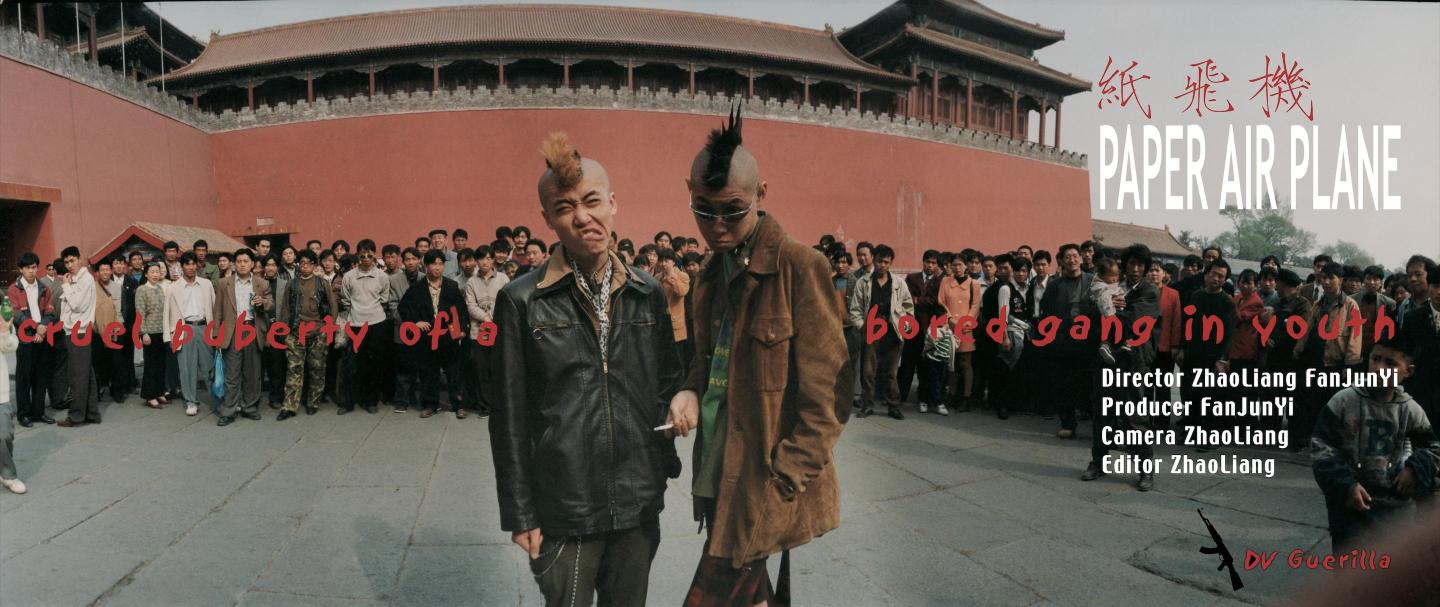

Critiquing the modern China has become a persistent theme in contemporary Chinese cinema, but questions were being asked even in the immediate aftermath of the reformist period of the late ‘80s and ‘90s. Zhao Liang’s Paper Airplane (纸飞机, Zhǐ Fēijī) is on the one hand a sort of celebration of the new freedoms, but it’s also fuelled by the sense of confused hopelessness which engulfed many of those who came of age post-Tiananmen and could no longer rely on the iron rice bowl of the communist era while new opportunities largely failed to appear.

Critiquing the modern China has become a persistent theme in contemporary Chinese cinema, but questions were being asked even in the immediate aftermath of the reformist period of the late ‘80s and ‘90s. Zhao Liang’s Paper Airplane (纸飞机, Zhǐ Fēijī) is on the one hand a sort of celebration of the new freedoms, but it’s also fuelled by the sense of confused hopelessness which engulfed many of those who came of age post-Tiananmen and could no longer rely on the iron rice bowl of the communist era while new opportunities largely failed to appear.

Zhao embeds himself deeply within a group of friends and relatives living a fairly bohemian existence on the fringes of the Beijing music scene. The film opens with a young man, Wang Yinong, cleaning a syringe with water while a young woman chats on the phone. Yinong has agreed to wait in for a friend, but then suggests going out to escort the woman home, as if he doesn’t quite want her to be there when the friend arrives. Shortly after, a young man in a leather jacket, Zhang Wei, turns up apparently having procured a small amount of drugs. Yinong asks him when he’s going to “kick” (the habit), to which he replies “in a few days” prompting an exasperated sigh from the woman next to him who exclaims that’s what everyone always says.

The rest of the film pivots around the various friends and their complicated relationships with drugs and the law. They get caught, often as part of complex entrapment schemes operated by the police, and are either fined and released or sent for rehabilitation which in the worst case scenario involves being sent to a reeducation labour camp. Only one of the group, Fang Lei, manages to evade the law but is himself later arrested and subsequently determines to kick the habit for good.

Fang Lei, sorting through a collection of pirated cassette tapes he sells on the streets in an attempt to earn a living (or at least money for drugs), puts it best when he says that by the time you realise that drugs are no good it’s already too late because you no longer need anything else. His sympathetic father sitting off to the side directly engages Zhao in one of the film’s few direct to camera moments when he pauses to remark that people need to see the stories of men like his son who have been left behind by their society, floundering around unable to find jobs with no one looking out for them.

Fang Lei does eventually manage to kick the habit, partly because he feels guilty for worrying his parents with his precarious lifestyle and partly, he admits, because this time he really wanted to. After getting off the drugs himself, he wants to help others do the same but knows all too well that you can’t help someone who doesn’t want to be helped. Another young woman, Liang Yang, attempts suicide by overdose after suspecting her boyfriend, a punk musician and fellow drug user, of cheating. She knows the drugs are bad for her and make her even more unhappy than she might be without them, but somehow she can’t seem to make the choice to live a different life and always finds herself returning to heroin. Unable to find a sense of positivity or an independent reason for living, she continues to seek escape from an unfulfilling existence in brief moments of drug-fuelled relief.

She too has a supportive mother trying to push her towards a more positive path, but the contrast here is starker. Liang Yang’s mother lives a humble existence little minding that she eats her dinner off a tiny tray on the floor of her kitchen and has learned to be happy with what she has. She doesn’t quite understand why her daughter can’t do the same. Fang Lei and Liang Yang’s boyfriend try to help her, even threatening to report her to the police so that she’ll have to go into rehab, but eventually have to concede defeat by giving her the money to buy methadone but leaving the choice of what to do with it up to her.

The “paper airplane” of the title is neatly explained by Yinong who, having been absent for much of the film, makes a surprise reappearance at its conclusion in a much reduced state. From a hospital bed he tells Zhao that he should call his film paper airplane because they’re bits of folded paper which sometimes fly very high but only for an instant before falling to the ground, paying a high price just for the chance to soar. Zhao had begun his film with a sense of youthful rebellion as these nihilistic youngsters forged a community of the dispossessed kicking back against an oppressive society, but he ends on a note of despair and futility which paints them as in some way trapped by the false promise of the modern China which denies them both freedom and a future. In an attempt to escape the crushing sense of impossibility and confusing lack of forward direction, they found fulfilment only in the “intense relaxation” of drug-induced highs but all too soon find themselves back on the ground again in the exact same place as they started with nothing much to show for their experiences other than regret and anxiety.

Screened as part of the 2019 Open City Documentary Festival in conjunction with Chinese Visual Festival.