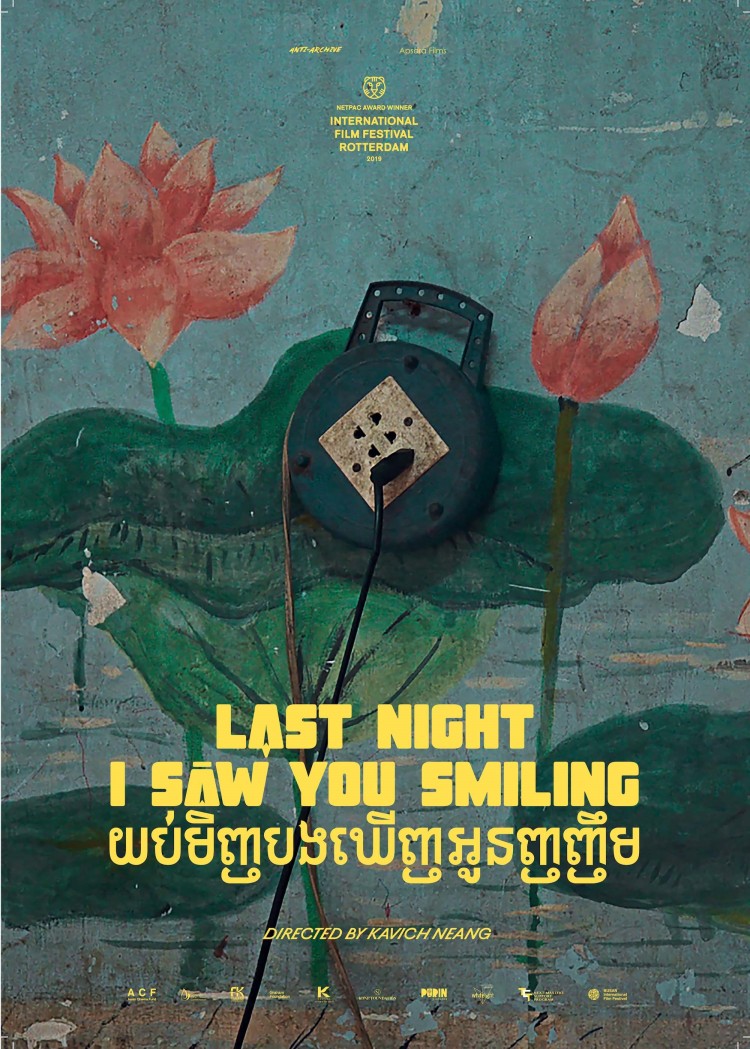

“We’re used to seeing a house for its roof, windows, and walls. But in the end, as we move out of here, it breaks my heart.” Words ironically offered by a sculptor, one who might above all have learned to fall in love with the shape of things, as he prepares to leave a place in which he has made his life. Filmmaker Kavich Neang grew up in the iconic “White Building” of Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Built in 1963, the building was a bold statement from a new nation as it threw off the colonial yoke to claim a new identity, literally extending the territory as it situated itself on reclaimed land – a well appointed complex of bright white stone amid the serenity of spacious parkland.

“We’re used to seeing a house for its roof, windows, and walls. But in the end, as we move out of here, it breaks my heart.” Words ironically offered by a sculptor, one who might above all have learned to fall in love with the shape of things, as he prepares to leave a place in which he has made his life. Filmmaker Kavich Neang grew up in the iconic “White Building” of Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Built in 1963, the building was a bold statement from a new nation as it threw off the colonial yoke to claim a new identity, literally extending the territory as it situated itself on reclaimed land – a well appointed complex of bright white stone amid the serenity of spacious parkland.

Intended to house those of moderate income, the White Building first fell into disrepair during the brutalising reign of the Khmer Rouge whose evacuation of the city left it empty for four years. In 1979 after the regime fell, the people began to return and the building once again became a beacon of culture in a modernising city, a vertical village home to artists and civil servants. Progress, however, began to work it against it, and by the time it was condemned in 2015 the building was regarded by many as a slum associated with drugs, crime, and sex work. Nevertheless, it was still home to 493 families, Neang’s among them, many of whom had lived there since the ‘80s and vividly recall the last time they were told they would need to vacate.

The anxieties are, of course, different, but they are there all the same. No one is marching them out by gunpoint, and they have a choice in where they go (in theory, at least), but the truth remains that people are being forced out of their homes against their will. While it is true that the building may have become unsafe and has been deemed unsalvageable despite attempts to preserve its architectural history, many worry that the promised compensation will never arrive or that, for those who lived in the smaller flats, they have been priced out of the modern Phnom Penh and will not be able to find equivalent accommodation using only the money they have been offered but have not yet received. This turns out to be more or less the case with many of the elderly residents returning to live with extended family, in some cases leaving the city entirely, while others retreat to the suburban margins.

In this sense, Neang documents his neighbours and family “burying” the building as they slowly dismantle the history of their lives within it. At an early meeting with officials, some are keen to confirm that they will be allowed to take doors and windows with them, and so we gradually see doorframes pulled away from walls and fretwork removed from the outside to be incongruously pulled back in. Yet others struggle to bundle their personal belongings, unsure of where they’re going or what they will need in the knowledge they will never, can never return because this place will eventually cease to exist.

Indeed, taking its name from a nostalgic pop song, Last Night I Saw You Smiling (យប់មិញបងឃើញអូនញញឹម) is a funeral elegy for the spirit of a place now departing. Neang opens with a silent corridor and then fills it with life – children playing, women singing, doors open in neighbourly communion. He ends in the same place as the building breathes its last, either liberated or devoured, transitioning to bright white light as if its soul really had departed to a better place. Retro pop songs fill the air singing of lost love, not only of its immediate pain but of the incurable longing of unfulfilled desire for a world that no longer exists and lives only in the halls of memory. You can never go home again, because “home” is a moment, a feeling which is always passing and forever elusive. People give a place soul, only to for that connection to be painfully severed when they must inevitably leave it leaving a piece of themselves behind. The White Building is gone, the community scattered, but the ghost of it lives on, invisible yet ever present.

Screened as part of the 2019 Open City Documentary Festival in partnership with Day For Night who will be distributing the film in the UK.

Festival trailer (English subtitles)