At times of tragedy it may be natural to look for someone to blame, as if being able to pin all of this pain and anger on a single source would somehow help you to accept it. But in other ways tragedy is just a confluence of circumstances that are either everyone’s fault or no one’s. How far back can you really trace the blame? There would be no end it. That’s perhaps the conclusion that the protagonists of Keisuke Yoshida’s Intolerance (空白, Kuhaku) eventually come to, realising that their attempts to blame others are often born of a desire to deny their own responsibility or else to protect something else they fear losing.

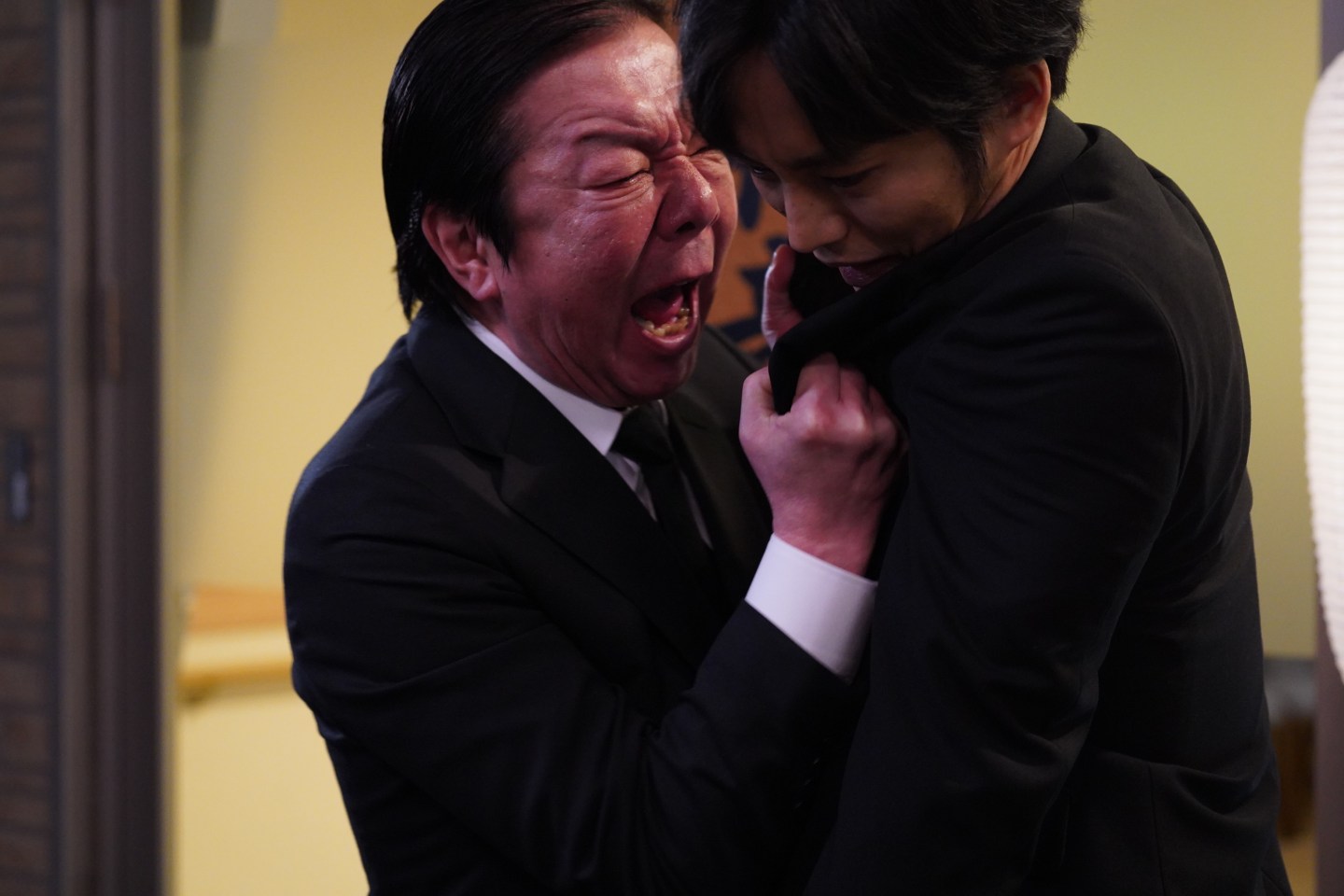

At least that’s how it is for grizzled fisherman Mitsuru (Arata Furuta), a man well liked by no one. A rude and violent bully, he terrorises all around him not least his teenage daughter Kanon (Aoi Ito) who is meek and passive with a slightly ethereal quality as if she’s learned that blending into the background is the best way to protect herself. Stopping in to a local convenience store on her way home from school, she’s accosted by resentful store manager Naoto (Tori Matsuzaka) who grabs her by the arm and accuses her of shoplifting nail polish. At some point, Kanon panics and bolts out of the store. Naoto chases her along a busy highway until she suddenly darts out into the road trying to get away from him and is hit first by a car driven by a young woman and then by a truck travelling in the opposite direction. Despite his gruff exterior, Mitsuru is quite clearly destroyed by his daughter’s death but becomes fixated on clearing her name of the shoplifting, insisting that he never saw her wear any makeup and that Naoto is to blame for her death in acting with such a heavy hand.

Of course, it doesn’t occur to Mitsuru that Kanon may have worn makeup in secret and made sure to keep it from him knowing how he’d likely react. Likewise, perhaps she ran from the store because Naoto would have called her father and she was frightened of what he’d do if he found out she was caught pilfering, and pilfering nail polish at that. He remembers that she wanted to talk to him about something to do with school the night before she died but he didn’t listen, assuming she must have been being bullied and was forced to steal the nail polish only to hear that no one at school really even remembers her. She was a just a vague presence they can’t even quite identify. Her teacher meanwhile begins to reproach herself, realising that she failed in her duty of care repeatedly shouting at Kanon that she had “no motivation” rather than trying to help her find some or to get along in her own way, let alone figuring out what caused her to behave the way she did or if there were problems at home. Sick of Mitsuru’s belligerence the school finally set him on the new target of Naoto who was once accused of molesting a teenage girl he accused of shoplifting.

Like Kanon, Naoto is a slightly hollow presence who also had a strained relationship with his father. As he lay dying, Naoto failed to answer his calls because he was playing pachinko and felt ashamed, afraid of another lecture from his dad about wasting his life on gambling. He struggles with his role in Kanon’s death, on the one hand guilty feeling he overreacted and inadvertently caused her to stray into harm’s way while otherwise resentful, justifying himself that it’s only natural for a storeowner to chase a shoplifter down the street. Both he and Mitsuru soon fall foul of a media culture that likes sympathetic victims and heartless villains, the media shocked by Mitsuru’s boorish behaviour but more so by Naoto’s callous indifference trimming an otherwise nuanced statement to imply that he feels his supermarket is the real victim as customers stay away or else issue complaints about their obviously heavy-handed shoplifter policy.

“Imposing your own views on others is nothing more than torture” Naoto tells a well-meaning middle aged woman whose narcissistic cheerfulness is a neat mirror of Mitsuru’s intimidating aggression. Aggressively mothered by Kusakabe (Shinobu Terajima), Naoto carries an additional burden of guilt in realising he’s lost the store his father left to him, but she embarks on a tasteless “real victim” campaign insisting they did nothing wrong and it’s all Kanon’s fault for stealing in the first place. Kusakabe can’t bear to lose the store because it seems there’s not much else in her life. The film’s Japanese title translates as “blank” or “void” and it is indeed a void that Kusakabe is trying to fill in needing to feel needed by centring herself in her various volunteer activities such as working at a soup kitchen in addition to her crusade to save the store.

It’s this giant abyss of grief and guilt which pulls each of them towards the edge, but in the end there’s really no way to apportion blame. The poor woman who first knocked Kanon down is completely undone by the experience though it really wasn’t her fault, repeatedly approaching Mitsuru asking for his forgiveness only to be cruelly rebuffed. It’s her mother’s (Reiko Kataoka) quiet show of dignity which stands in such stark contrast to his own white hot rage that finally forces him to realise the destructive quality of his intimidating behaviour, accepting his responsibility in his daughter’s death while understanding that in his fierce desire to control he robbed himself of the ability to know her. Really you can’t say whose fault it was, Mitsuru’s for the fear he instilled into his daughter, Naoto’s for his insecurity and misplaced zeal in hunting down a thief, the drivers’ for failing to brake, Kanon’s mother’s (Tomoko Tabata) for remarrying and having another child, the teacher’s for making Kanon feel useless, the other kids’ for rejecting her, or Kanon’s own for darting out into the road. For each of those there are a hundred other branches. There would be no end to it. But then, the strange thing is that Kanon shares her name with Buddhist deity of mercy, Mitsuru beginning to soften now willing to offer an apology where it’s due and to bear his own degree of guilt if not yet entirely able to forgive. In any case, ending in bright sunshine, Yoshida concludes with a return of the gaze between father and daughter that suggests forgiveness may indeed have arrived.

Intolerance screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Original trailer (English subtitles)