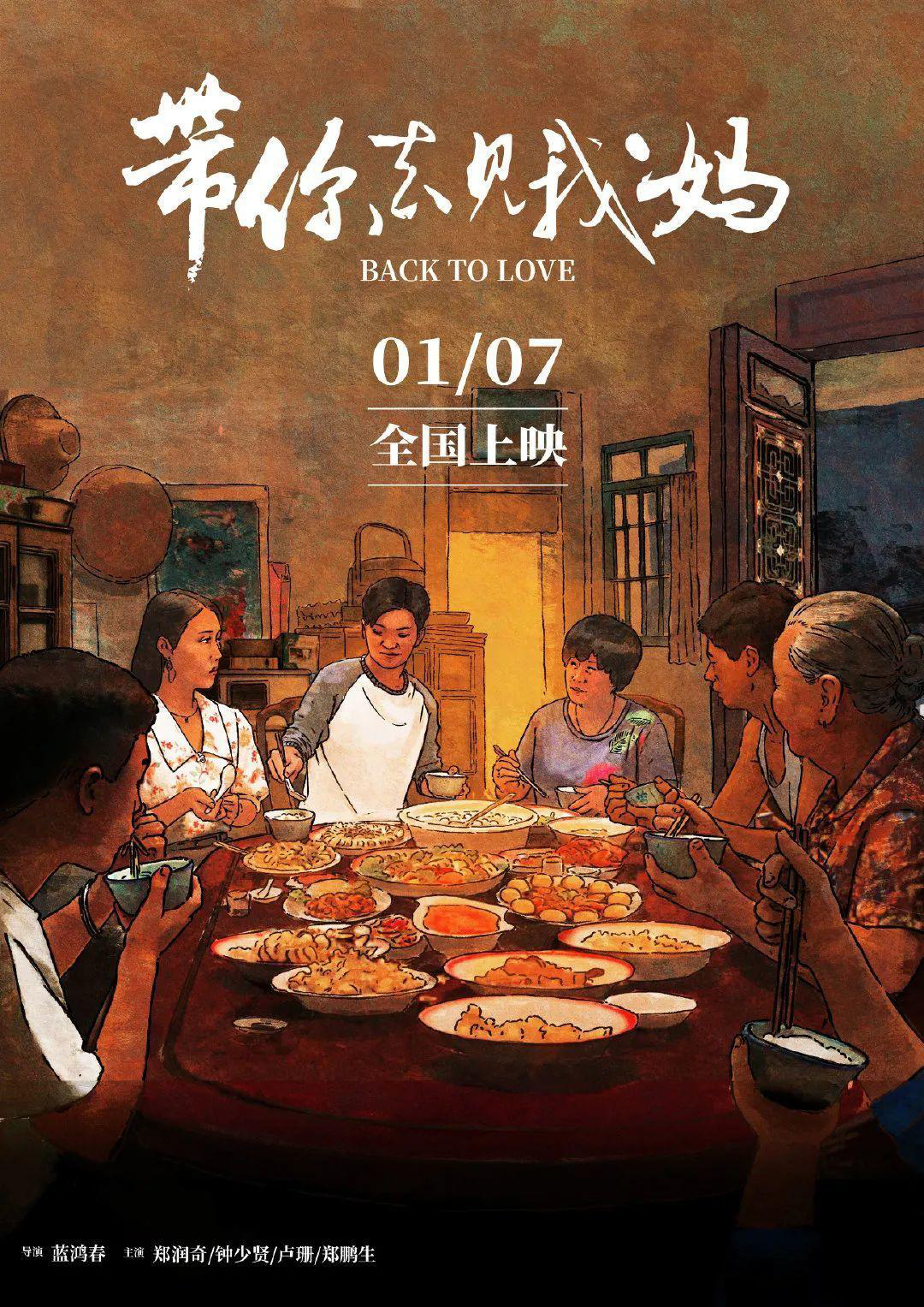

Change comes slow to rural China in Lan Hongchun’s lighthearted drama, Back to Love (带你去见我妈, dài nǐ qù jiàn wǒ mā). Shot largely in the local Chaozhou dialect, the film explores the increasing distance between the kids who left for the city and their small-town parents whose views are often more conservative especially given the fluctuating local hierarchies which are often defined by successful marriages of the children. True love may be hard-won in a sometimes judgemental society but it is in the end the older generation who will have to make a shift if it’s really their children’s happiness that they care about most.

Xian (Zhong Shaoxian) runs a backstreet butcher shop in a small rural town and lives with her retired husband, who is also a performer of traditional opera, her elderly mother, and her youngest son. Engaged in a sort of competition with another local old lady, Xian is forever trying to organise blind dates for her older son who works in a warehouse in the city. Unbeknownst to her, Zekai (Zheng Runqi) already has a girlfriend, Shan (Lu Shan), and the pair have been living together for some time. Though his uncle who works with him already knows about the relationship, Zekai has been reluctant to tell his family back home because not only is Shan not from their local area but has also been married once before which he knows will not play well in his hometown where divorce and remarriage are still taboo subjects. As his uncle advises him, his diffidence is unfair to Shan who deserves a little more commitment along with the possibility of starting a family before the chance passes her by.

Having thought it over, Zekai proposes and talks about becoming a father while suggesting they visit his family en route to her hometown for a wedding but still hasn’t explained to his parents about Shan’s marital status. Their immediate problem with her, however, is simply that she isn’t from the Shantou area and does not understand their local dialect while, living as they do in a fairly isolated community, they do not understand standard Mandarin. Xian and the grandmother who is otherwise more accepting of the situation continue to refer to Shan as “the non-local” while she does her best to pitch in, learning little bits of dialect and helping out as much as she can with the family’s ancestral rites while getting on well with Zekai’s already married sister.

Gradually Xian warms to her, but the divorce may still be a dealbreaker given Xian’s preoccupation with her status in the local community reflecting that the family would become a laughing stock if people find out their already old to be unmarried son stooped to marrying a divorcee. Most people don’t mean any harm, but there are also a lot of accidentally hurtful comments about a wedding being a once in a lifetime affair and that a woman should stick by the man she married no matter what else might happen. But then it’s also true that Zekai has been keeping secret from his mother and she can’t help but feel deceived. If he’d told her earlier, she might have just got over it after getting to know Shan personally. At the end of the day, perhaps it’s Zekai’s own internalised anxiety that’s standing in the way of his romantic happiness rather than the outdated social codes of small-town life.

As Zekai points out, he’s always done what his mother told him to. He wanted to study fine art and she convinced him to switch to general sciences but in the long run it hasn’t made a lot of difference to his life and he might have been happier doing what he wanted. The couple could of course choose to just ignore Xian’s resentment and continue to hope she’ll change her mind in the future, but then Shan is also carrying some baggage in internalised shame over her failed marriage. She didn’t think she’d marry again not because of the bad experience but because of the stigma surrounding divorce, fearing she’d never have the opportunity. In any case, it’s Xian who finally has to reconsider her actions, accepting that she may have unfairly projected some of her own feelings of disappointment onto her son while accidentally denying him the possibility of happiness solely for her own selfish reasons in fearing a change in her status in the community. Filled with local character, Lan’s gentle drama doesn’t necessarily come down on either side but advocates for compromise while clear that the youngsters should be free to find their own path to love with nothing but gentle support from all those who love them.

Back to Love streams in the US Sept. 10 – 16 as part of the 15th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (Simplified Chinese / English subtitles)