“This shit’s for real.” according to the front desk guy at Hotel New Mexico, an out of the way spot just perfect for those looking to lay low for a little while. Like a lot of Katsuhito Ishii’s work, Party 7 is essentially a series of self-contained vignettes which eventually collide following a series of bizarre coincidences revolving around some money stolen from the mob, a two-way mirror in a regular hotel room, and the receptionist’s tendency to almost literally shoot the shit.

Following a brief prologue, Ishii opens with striking animated sequence which introduces each of the main players with an arcade game aesthetic and explains that Miki (Masatoshi Nagase) has stolen money from the mob and is currently on the run which is why he’s turned up at the infinitely weird Hotel New Mexico. The running gag is that Miki thinks he’s holed up somewhere no one will find him, but sure enough a series of “friends” soon turn up in part thanks to a loose-lipped travel agent. The fact that people can find it so easily dampens the impression of the Hotel New Mexico as some kind of interstitial space. It’s not so much existing in a weird parallel world as a bit run down and staffed by a series of eccentrics. It does however have a “peep room” hidden behind a two-way mirror where “Captain Banana” (Yoshio Harada) is attempting to pass his knowledge on to the young Okita (Tadanobu Asano), the son of a recently deceased friend who has been repeatedly arrested for voyeurism.

Captain Banana’s insistence on his surreal superhero suit is in a way ironic, if perhaps hinting at the super empowerment of accepting one’s authentic self. “It’s your soul,” he tells Okita, “it’s screaming ‘I want to peep’.’” Meanwhile, Miki gets into an argument with his ex-girlfriend Kana (Akemi Kobayashi) who has turned up in the hope of reclaiming money that he owes her. Kana too seems to be less than rigorous with the truth if perhaps emotionally authentic. She’s now now engaged to a nerdy guy having somewhat misrepresented herself as the innocent girl next-door type. Her refusal to let her fiancé into her apartment perhaps hints at a more literal barrier to intimacy or at least that she is intent on preventing him from seeing her true self. What she doesn’t know is that her fiancé hasn’t been completely honest either, in part because he thinks she’s out of his league and is insecure in their romance.

Miki too maybe somewhat insecure, having run off with the gang’s money after hearing them bad mouth his associate Sonoda (Keisuke Horibe) who has now been charged with killing him and getting the money back. But Sonoda too has reasons to doubt the boss’ affection for him after Miki and the others point out that gifts he thought were so valuable are really just cheap knock offs that suggest the boss thinks very little of him at all. Okita’s psychiatrist tells him that there are “no rules in making friends”, and maybe in a strange way that’s what everyone is trying to do. Kana wanted the money to overcome her anxiety about having no friends or family to invite to the wedding, while all Sonoda wanted was the boss’ approval and though Miki had deliberately gone somewhere he thought no one would find him nevertheless attracts a series of followers.

Even the receptionists seem to be desperate for human contact with their strange stories of poo falling from the sky and bizarre approach to hospitality. “The point is whether you believe it or not,” one tells the other after spinning what sounds like a yarn but then again might not be. Ishii’s zany world has its own surreal logic culminating in a piece of cosmic irony and defined by coincidence as the otherwise unrelated stories begin to come together and slowly find their way to Hotel New Mexico but seems to suggest the point is in the serendipity of the meeting and its concurrent authenticity even if a literal shot in the arm is a less than ideal way of brokering a friendship.

Party 7 is released in the UK on blu-ray on 17th July as part of Third Window Films’ Katsuhito Ishii Collection.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

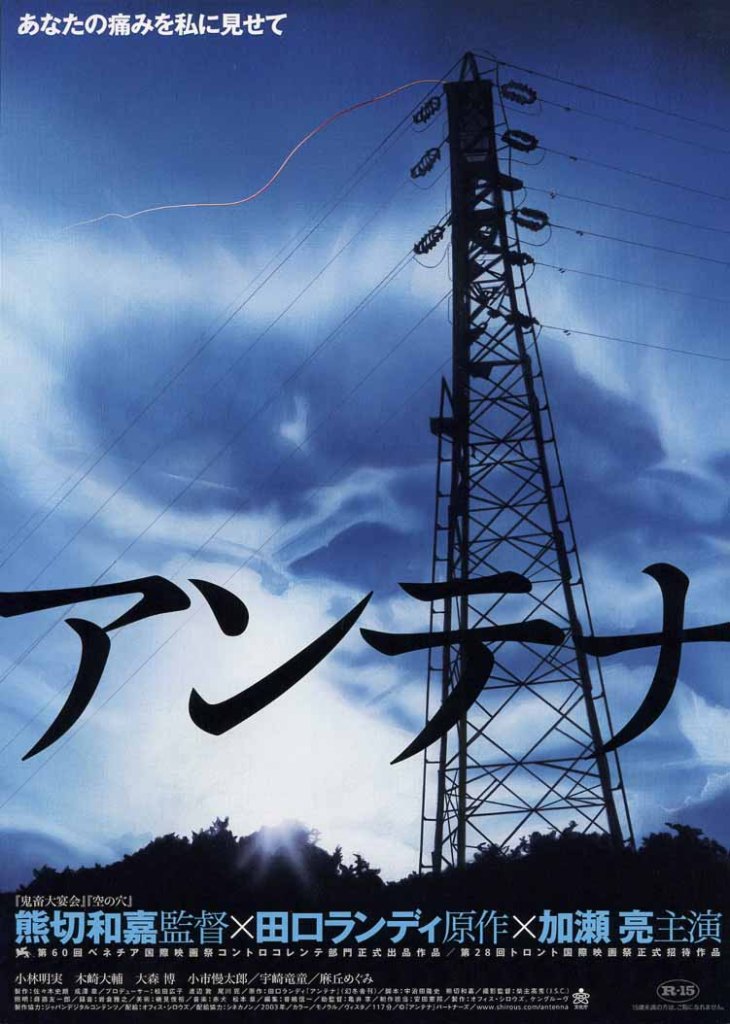

Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.

Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.