A quartet of Thai directors come together for four tales of horror in the appropriately titled 4bia (สี่แพร่ง). Though the stories are largely unconnected save for a few common details that locate them in the same universe, they each deal with a particular kind of anxiety and different sorts of ghosts who for various reasons are haunting the protagonists. What’s certain is that if you’re targeted by an otherworldly spirit, finding escape will not be easy.

That’s something quite obvious even in the first episode in which a young woman trapped alone in her apartment after breaking her leg in a horrific car crash begins chatting with a total stranger who sends her a random text message. Of course, replying to a message like that is not very sensible and even perhaps dangerous, as Pin (Maneerat Kham-uan) herself may release when she asks the (presumably) male messenger to send a photo only to be sent back the one she just sent of herself with the reply that he’s in it next to her. In any case, the real malevolent force here seems to be loneliness itself which is what motivates Pim to message back having already spent 100 days without interacting with another human being. The messenger has also spent the same amount of time alone in what he calls a “cramped space,” which is why he wants company. It’s gradually revealed that the pair share a kind of destiny which is an inversion of the kinds of meet-cutes you might find in a romantic comedy that makes Pim’s 100 days a purgatorial space of borrowed time in which she might as well have been a ghost herself.

But in the second chapter, Tit for Tat, it’s almost the opposite of loneliness that’s the problem as bunch of delinquent high school students and recreational drug users bully a bookish boy, Ngid (Nattapol Pohphay) and end up killing him. The boy then becomes a vengeful spirit and uses black magic to take them all out. Though one of them quips that they need to start smoking less weed, there’s no real question that the ghost is real or that the gang pretty much deserve what’s coming to them for having been so obnoxious in real life. The later part of the drama focuses on Pink (Apinya Sakuljaroensuk), a peripheral member of the gang who did try to tell the others to stop but otherwise did nothing to help Ngid and is punished for her sin of omission, though she does eventually think of a way to break the curse if only ironically in poetic justice for simply standing by and watching in the face of injustice.

The third sequence, Banjong Pisanthanakun’s Man in the Middle is, however, a meta textual-delight that asks why ghosts in films always have long hair and pale faces. Four boys go on a rafting trip and swap campfire stories about how you should never sleep on the end when you’re close to the jungle in case a succubus comes to get you. When they get into an accident on the water and are separated, it leads to a sense of suspicion as some wonder if their friend actually died and is a ghost come to haunt them who, like in the Sixth Sense, may not know he’s dead. Though the twist maybe somewhat predictable, the tale is told with good humour and a sense of narrative cohesiveness that is lacking in some of the other chapters.

Similarly, the final instalment Last Fright, is a chamber piece focusing on a stewardess who is unexpectedly charged with escorting a princess (Nada Lesongan) who’s fallen out of favour on her trip to Thailand where she spent her honeymoon. Pim’s (Laila Boonyasak) secret is that she’s been having an affair with the princess’ husband whom she met on their honeymoon flight which is why the incredibly imperious woman tortures her all the way through the flight before dying in a hotel room on arrival. Pim must, for reasons that don’t really make sense, escort the body back only to begin going out of her mind while haunted by the princess’ spirit. This is the only sequence which flirts with the idea of the ghost not actually being real but a manifestation of Pim’s guilt, or else a vengeful spirit come to punish her not for her secondary crime but for the transgression of adultery. Despite its potentially moralising overtones it’s a pretty chilling moment on which to end the film suggesting that in the end there is no real escape either from a vengeful ghost or your own questionable decisions.

4bia is available as part of Umbrella Entertainment’s Thai Horror Boxset.

International trailer (English subtitles)

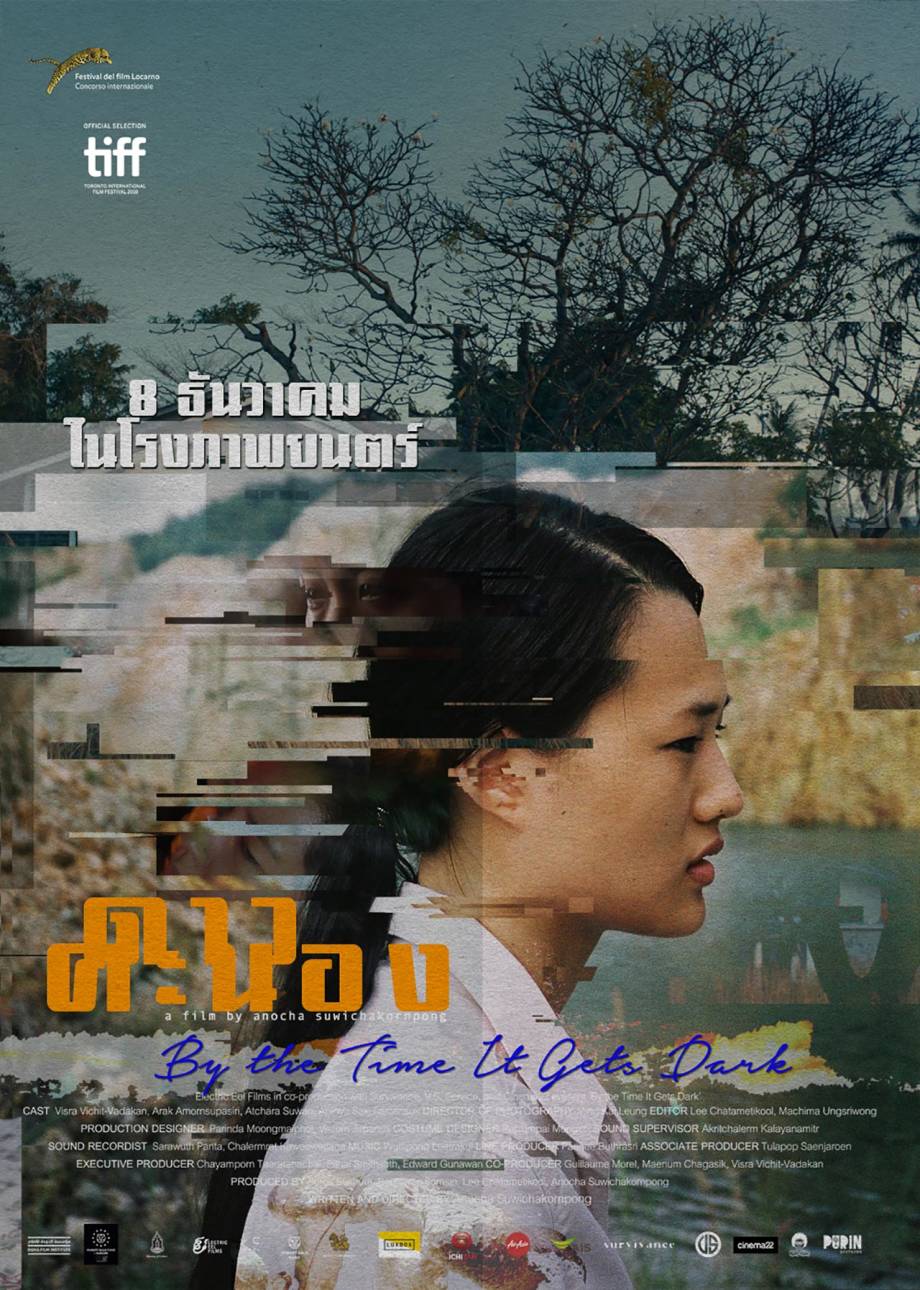

Anocha Suwichakornpong’s second feature, By the Time it Gets Dark (ดาวคะนอง.Dao Khanong), bills itself as an exploration of a traumatic moment from the recent past but quickly subverts this conceit for a wider meditation on the veracity of cinema. Beginning in a manner typical of indie-leaning Thai films, Anocha gently undercuts herself as her images prism into their separate “realities”, informing and commenting on each other but perhaps not fully interacting. The Thammasat University student massacre of 1976 is the dark genesis of this fracturing future, but it’s also in the process of becoming a collective legend, cementing a “historical truth” as cultural currency even whilst expunged from the history books, leaving its young lost in a black hole of memory from which they are powerless to emerge.

Anocha Suwichakornpong’s second feature, By the Time it Gets Dark (ดาวคะนอง.Dao Khanong), bills itself as an exploration of a traumatic moment from the recent past but quickly subverts this conceit for a wider meditation on the veracity of cinema. Beginning in a manner typical of indie-leaning Thai films, Anocha gently undercuts herself as her images prism into their separate “realities”, informing and commenting on each other but perhaps not fully interacting. The Thammasat University student massacre of 1976 is the dark genesis of this fracturing future, but it’s also in the process of becoming a collective legend, cementing a “historical truth” as cultural currency even whilst expunged from the history books, leaving its young lost in a black hole of memory from which they are powerless to emerge.