A man denied a fair chance in life because of his impoverished background comes to identify with the plight of those carrying the hepatitis B virus in Wang Jing’s true life drama, The Best is Yet to Come (不止不休, bùzhǐ bùxiū). Inspired by the story of Han Fudong, a journalist who exposed the societal prejudice against those with a previous diagnosis of the disease, the film’s Chinese title “no pause no rest” makes clear how tirelessly he strived to reveal the truth even at the potential cost of destroying his dream of becoming a professional reporter.

Han Dong (Bai-Ke) came to Beijing in 2003 in the hope of landing a job at a paper, but just like everywhere else journalism is a largely closed profession almost impossible to break into without elite qualifications and connections. At a jobs fair, Han Dong tries to pass off his reluctance to hand over a CV as a recruitment tactic to get people to remember him, circulating copies of his portfolio instead though recruiters quickly lose interest on realising they are all self-published articles posted online. Once he admits that he only finished middle school, it’s game over no matter how talented a writer and investigator he may turn out to be.

It’s this sense of unfairness, of being turned away on the grounds of a few words on a piece of paper that eventually leads him to sympathise with those carrying the hepatitis B virus after investigating a company that claims it buys blood, discovering that they provide a service helping people to forge health certificates for job and school applications. Vox pop-style interviews recreated in the manner of the time feature several people describing the various ways their lives have been ruined simply because they happen to carry the virus, many of them infected since birth or early childhood. One man has been trying to apply for jobs and graduate schools for several years but finds the offers are always withdrawn after the health screening, while another woman recounts that her fiancé cancelled their engagement because his family could not accept someone with hepatitis B.

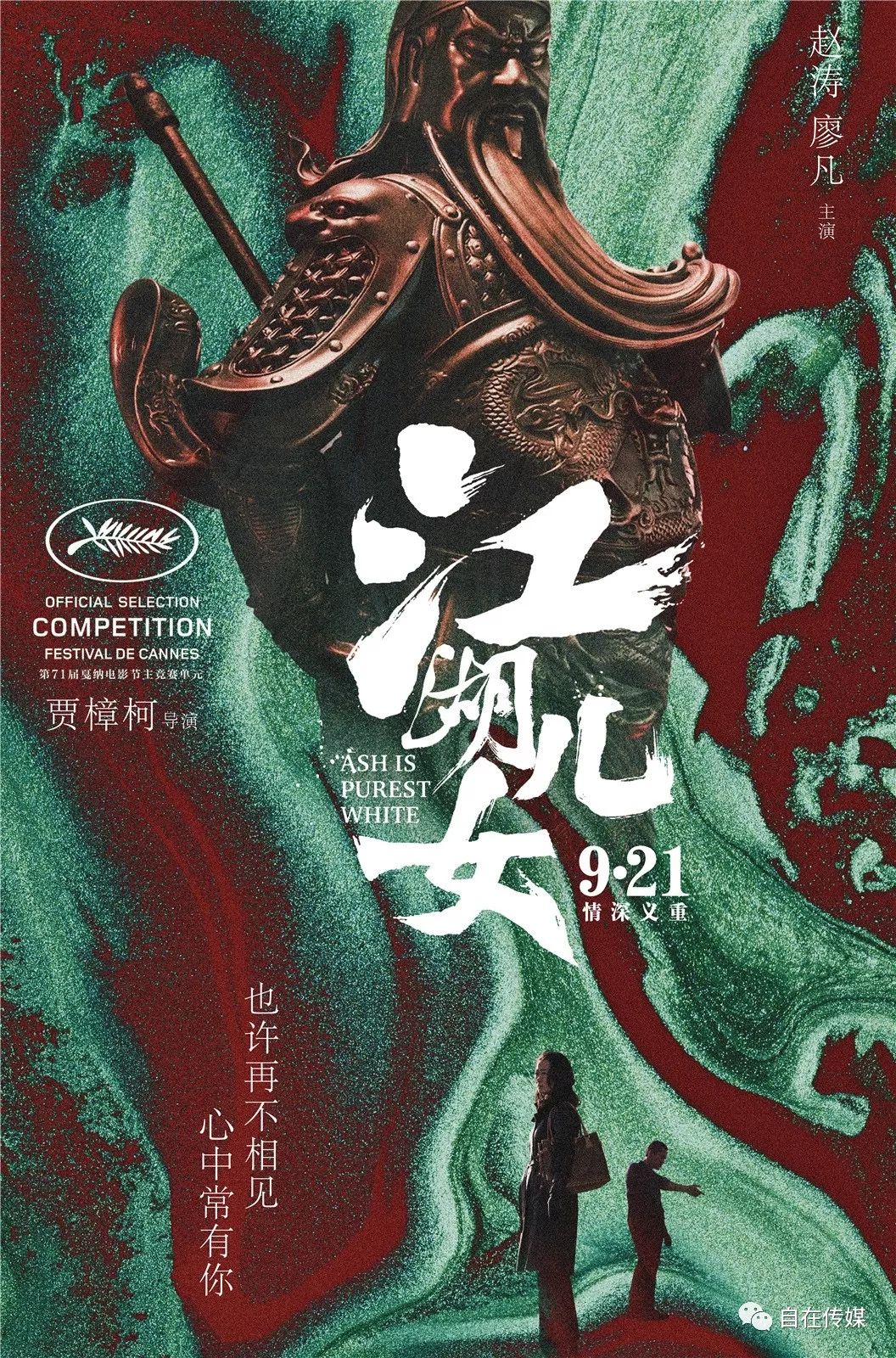

This is also in the immediate aftermath of the SARS epidemic which perhaps caused a preoccupation with infectious disease which may be largely unfounded in the relative difficulty of passing on the hepatitis B virus. After landing a golden opportunity of an unpaid internship compensated only with 50% article fees, Han Dong finds himself conflicted. He knows the forgery operation is illegal and a threat to public health, but also cannot blame the people who make use of it when their lives have been rendered so impossible that is difficult for them simply to live. An early assignment had seen him cover a mine collapse and witness a destraught mother bounced into accepting compensation for her son’s death while shouted at by the foreman (played by film director Jia Zhangke who also produced) for having the temerity to ask to see his body. Han Dong got a front-page byline as co-author with his mentor figure, Huang (Zhang Songwen), but wonders what the point is if nothing ever changes and the truth is not enough on its own.

For obvious reasons, films about crusading journalists are rare in Chinese cinema given that whistleblowing is not regarded as a virtue and those who try to expose wrongdoing are often shouted down or hounded into silence as seen with the doctor who drew attention to the poor medical practices in rural blood clinics that caused an HIV epidemic in farming communities, and most recently with the physician who tried to raise awareness of the new respiratory illness that later developed into a global pandemic. Journalists who report problematic stories can also find themselves facing prosecution and imprisonment. Han Fudong’s writings did however lead to an eventual change in the law and the destigmatisation of hepatitis B while he himself overcame the educational elitism of the contemporary society to achieve his dreams of becoming a professional reporter. As such, Wang’s dramatisation of his life may be in a way subversive if subtly so in hinting at a greater role for a currently not so free press in the modern China while also embracing a central philosophy that one need not simply accept an unacceptable status quo but actively reject and challenge it and that by doing so something might actually change.

The Best is Yet to Come screens in Chicago Sept. 30 as part of the 17th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema

International trailer (English subtitles)