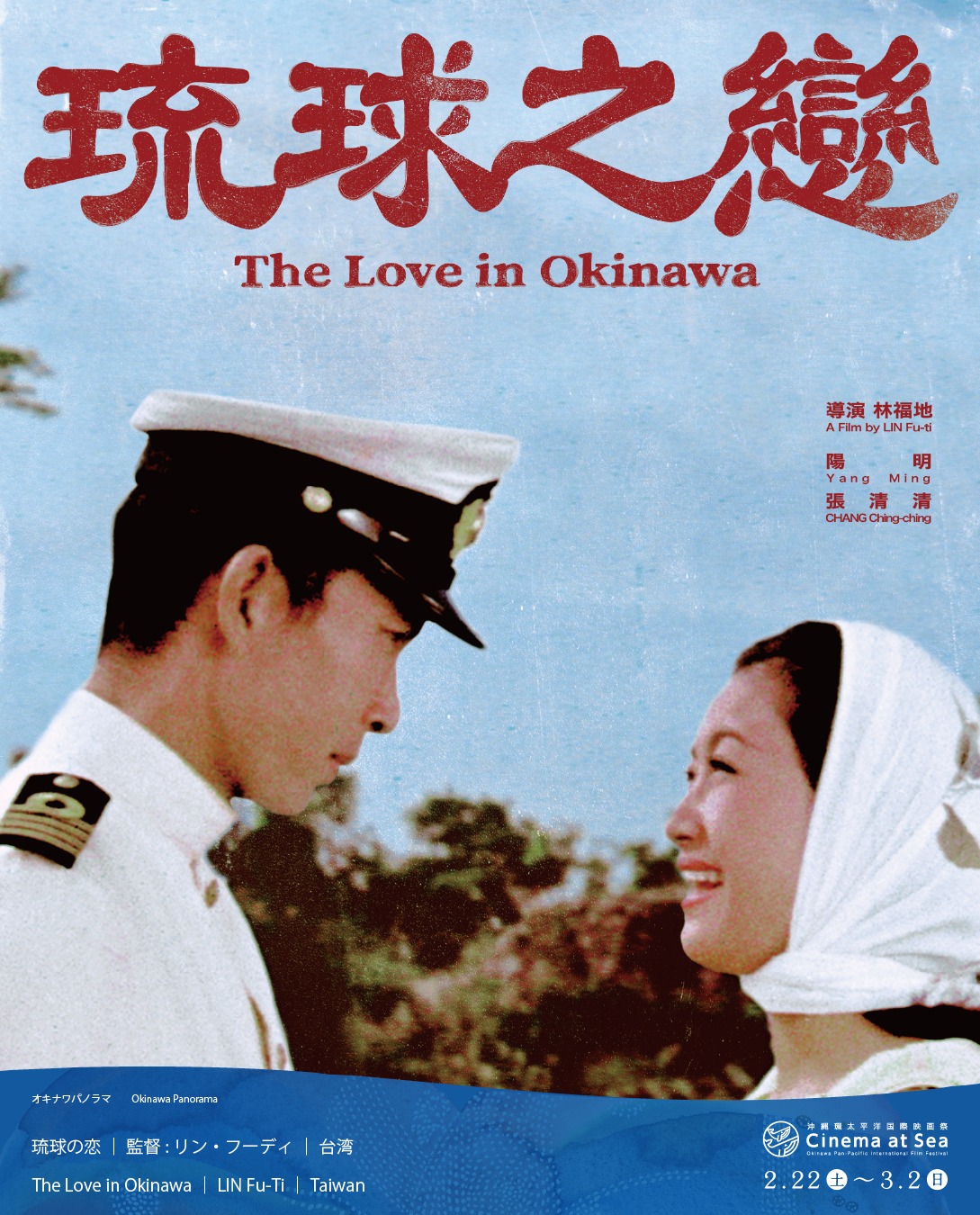

Though he may be captain of his own boat, a young man finds himself powerless in the matters of love in Lin Fu-Ti’s Taiyupian romance, The Love in Okinawa (琉球之戀). Long thought lost and recently restored from a Mandarin-dubbed print discovered in San Francisco’s Chinatown, the film was a collaboration between Taiwan and locally based film companies completed shortly before the islands’ return to Japanese sovereignty after an extended period of American occupation. Though the two nations share a degree of common ground in their experience of Japanese colonialism, the film seems to suggest that nothing really good comes of trying to do business here and events might have progressed differently if the family had not delayed its return to Taiwan.

Nevertheless, the real problem is that Hung-hai is a boat captain who in theory possesses the total freedom of the wide open seas yet he is unable to defy his father and marry the woman he loves out of a sense of filial piety. Hung-hai and Hsui-ling were childhood friends and their fathers were once like brothers only to be forced apart by a business dispute ending in a court case which Hung-hai’s father lost. Hsiu-ling’s father’s business later went bust anyway and he has been dead for several years but Hung-hai’s father still harbours fierce resentment towards him. The family went through a period of financial hardship following the court case during which Hung-hai’s mother worked herself to the bone gathering money for their new start. Hung-hai’s father blames his former friend for hastening his wife’s early death which is why he can’t accept Hsiu-ling, to whom he was once like an uncle, as his daughter-in-law.

But on the other hand he also has his own plans for his son’s life which include marrying Yoshiko. Yoshiko is the current “Miss Okinawa” and a minor celebrity who appears on television singing Japanese songs such as Mari Sono’s 1966 hit Yume wa Yoru Hiraku. She is always dressed in kimono, while Hsui-ling wears more westernised contemporary fashions but is later seen in more recognisably Chinese-style after her return to Taiwan. To that extent, Yoshiko represents a closer union with the growing economic powerhouse of Japan as mediated through Okinawa, while Hsui-ling represents an unsullied Taiwan yet one still restrained by increasingly outdated notions of filiality.

Eventually, after a series of ironies, Hung-hai’s father is forced to admit that his authoritarianism and refusal to allow his son to chart his own destiny has destroyed his family’s future. Unable to marry Hsui-ling who thinks that he has married Yoshiko after seeing her announce their engangement on television while he was away on his boat, Hung-hai falls into depression and takes to drink. Though he had long favoured Hung-hai to take over the business over his older son Ah-qin who has a physical disability and was therefore left behind in Taiwan to babysit the domestic business, Hung-hai’s father begins to realise the mistakes he has made and that in this ruined state Hung-hai will never amount to anything nor prove a worthy heir for his business empire.

Ah-qin, meanwhile, is oblivious to all this and the soul of kindness and decency. In some ways, he might play into a stereotypical vision of disabled people as saintly and innocent, yet is unwittingly drawn into his brother’s romantic drama knowing nothing of his father’s animosity towards Hsui-ling and her family nor of his brother’s love for her which is the cause of his depression. He wants only for everyone in his family to be happy, and in the end is willing to sacrifice his own happiness to facilitate it (which is a paradoxical expression of “positive” filiality). Hung-hai had suggested simply running away and eloping to Taiwan but Hsui-ling’s mother was on her deathbed and neither of them really had the stomach to abandon their parents in a “foreign” land. Thus this kind of filiality that divides the lovers is nothing but destructive. Not only does it ruin the family entirely, disrupting the relationship between the brothers as well as between father and sons, but leads only to futility and heartbreak in which true freedom is found only in death.

The Love in Okinawa screens as part of this year’s Cinema at Sea.

Trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)