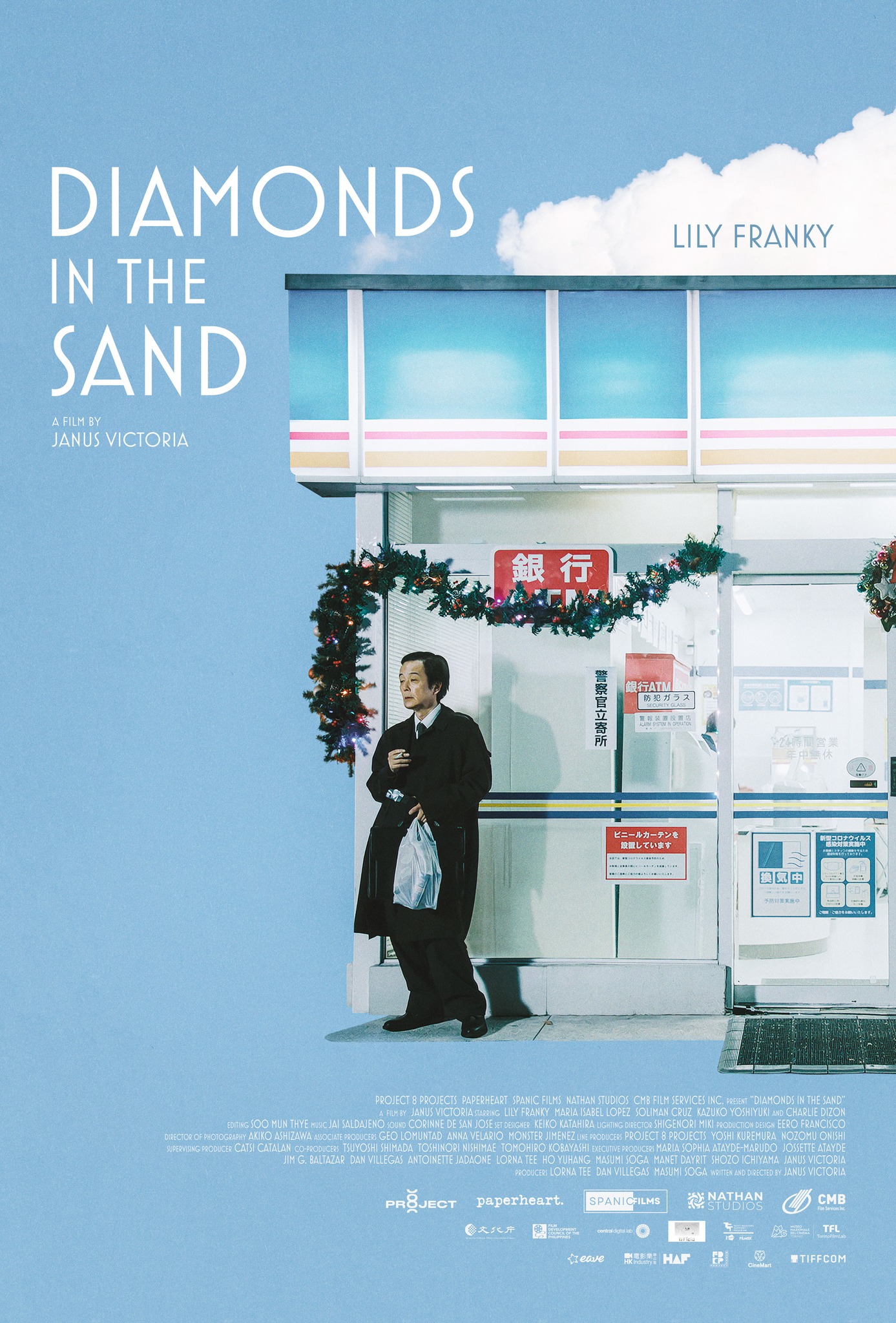

A middle-aged salaryman is awakened to the depths of his loneliness when his upstairs neighbour dies in an apparent lonely death in during the pandemic in Janus Victoria’s Filipino co-production, Diamonds in the Sand (砂の中のダイヤモンド, Suna no Naka no Diamond). Contrasting an epidemic of loneliness with the more literal spread of Covid-19, the film finds its hero trying to redefine his life and discover what gives it meaning in making connections with others.

Yoji (Lily Franky) is indeed an isolated man whose world is shrinking around him. The DVD department of a large manufacturer where he works has been wound up and he’s been transferred to one that seems to deal in pornography is basically four men in a room with nothing to do. It’s no surprise that he tells his bosses he doesn’t need his computer when they go remote during the pandemic. A large clock seems to tick out his remaining time as if reminding him that his life is running out. Things aren’t much better at home, either. Divorced, he lives in a tiny, colourless flat and seems to have few friends. He’s aloof from even those he does know and always stands slightly outside of the group. One of his former colleagues has been given a big promotion, but it involves moving to Thailand which Yoji seems to regard as a kind of exile or age-based banishment even as he reminds them how much Japan has invested in the nation.

Yoji first becomes aware of the death of his upstairs neighbour when his discomposing body begins leaking through his ceiling. Staring at the stain left behind, he begins to contemplate the reality of his own lonely death and the meaninglessness of his life. He begins going to visit his mother in a care home and trying to rebuild a meaningful relationship with her, but she also asks him if he’s ever really been happy in his life. Though her body is failing and her days are sometimes dull or lonely, the memories of past happiness sustain her. If Yoji doesn’t even that, then his old age would be even more miserable and his life not worth living. The only spark of joy is a colourful pinwheel he bought for his mother on a whim but enlivens each of their worlds with a sense of fun and vibrancy.

This sense of encroaching isolation and emptiness is directly contrasted with the bustling streets of Manila which are alive with colour and life and where, Yoji is told, there is no loneliness. Minerva (Maria Isabel Lopez), the middle-aged woman who looked after his mother in the care home, is one of many working abroad to support a family in the Philippines and experiencing different kinds of loneliness and isolation in Japan. She has an almost grown-up daughter, Angel (Stefanie Arianne), whose father was Japanese, but she was not really accepted by his family and struggles to find a place for herself in either society. After abruptly travelling to Manila in search of a life less lonely, Yoji becomes to her almost a surrogate father offering the reassurance and connection that her own father obviously did not.

But Minerva has a point when she says Yoji lacks compassion and even after being warmly accepted by the community in the Philippines and witnessing their interconnected way of life refuses to become fully a part of it or to help others when they are in need. He sees coverage of extrajudicial killings on the television and is confronted by the fact that life is cheap here too, but is also judgemental and unwilling to fully embrace the community around him. Still, he ironically comes across a kind of graveyard of “surplus” Japanese goods like Mr Suzuki’s bowls that the house clearance staff patiently boxed up and threw away as if erasing his existence. One of the ashtrays still has ash in it. It’s this that perhaps enlightens him to what’s really important in life and convinces him of the necessity of accepting his responsibility to others rather wanting love connection from them without really thinking about giving anything in return. Like looking for diamonds in the sand, it’s the little things that matter and just asking someone if they’ve eaten yet can in its way save a life.

Diamonds in the Sand (砂の中のダイヤモンド, Janus Victoria, 2024) screened as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

Trailer (English subtitles)