“It’s all pointless anyway, so let’s just do whatever we feel up to,” according to the sometime protagonist of Dong (东), the first in what would become Jia Zhangke’s artist trilogy. Shot alongside Still Life, Jia’s profile of artist Liu Xiaodong takes him from the soon-to-be drowned world of the Three Gorges to the floating Bangkok in a seeming inversion of his artistic pursuits but also perhaps contemplating his role and significance as an artist in the face both of great change and immutable legacy.

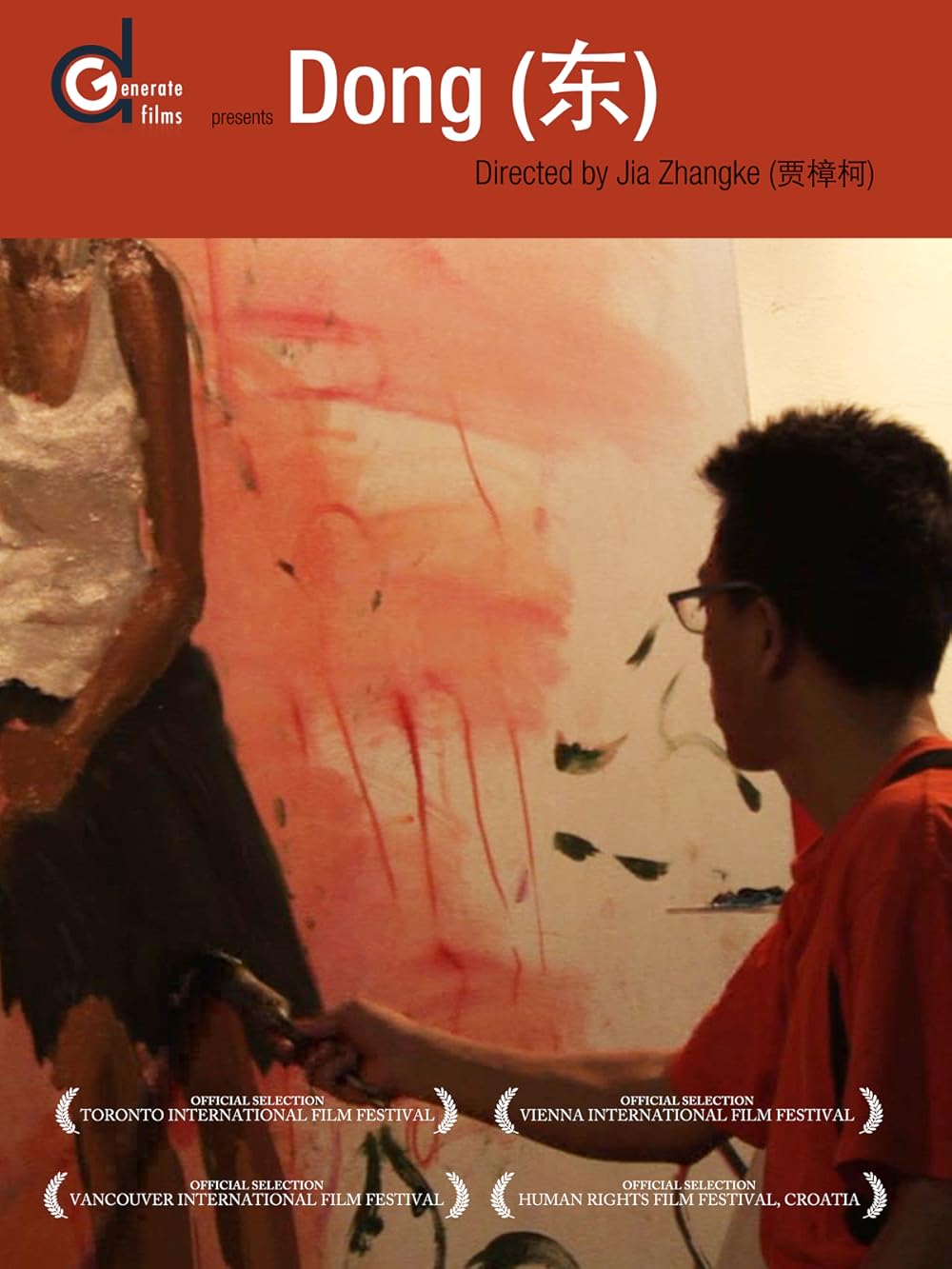

Liu’s primary project in the Three Gorges is to document the existence of the labourers working to dismantle the town of Fengjie prior to its drowning by means of one of his five-part paintings. He tells us that he likes to be able to see his subjects from far away to gain greater “distance and precision”, looking down on them from above as if he were standing on a wall. He is, in a sense, already elevating himself, adopting a somewhat elitist view as an all-seeing artist even as he is careful to redraw reality through advanced theatrical staging which sees the men dressed only in a pair of blue trunks as they “relax” on a rooftop with the mountains behind them. Yet we also see him as a tiny figure roaming the increasingly ruined landscape of Fengjie, lost amid its emptiness or dwarfed by the endless majesty of the Gorges. His insignificance is perhaps brought home to him when he makes a difficult journey obstructed by flooding to the home of one of his subjects who recently passed away in an accident, bringing with him fancy toys for the children and photographs for the adults but equally out of place in this man’s home, an intruder on their grief and accidental narcissist scene stealing at a funeral.

It is perhaps this sense of displacement that sends him to Thailand where he admits he understands nothing and can only “comprehend the human face, the girls’ scantily clad bodies”. Taking his subject as a collection of local sex workers, he has not chosen a natural background for the paintings as he usually would but can only “focus on the body in its elemental form”. Yet in contrast to his depiction of the labourers, his female models are in fact not particularly scantily clad at all even as they’re painted with a detached melancholy in opposition to the cheerful camaraderie of the workers relaxing on the roof. Indeed, Liu seems to have a preference for the vigour and vitality of the male form, making a rather unexpected remark on the magnificence of one young man’s penis before launching into an explanation of his practice of martial arts as a means of self-defence against a flawed legal system.

“If you attempt to change anything with art, it would be laughable,” he later tells us, explaining that the most he can do is try to express himself, admitting in a sense that he too exploits his subjects in turning them into art which is intended to critique their exploitation. “I wish I could give them something through my art. It’s the dignity intrinsic to all people,” he somewhat pompously adds, as if he thought them robbed of their dignity before and that it was something in his power alone to bestow before going on to lament that he resents the primacy of the Western tradition, revealing that he’s begun to admire the “visual impact of historical relics” of ancient Chinese art which has led him to value the ruined and incomplete. But then he adds, it’s all pointless anyway, you might as well do what you feel, later voicing his anxiety as an artist operating in relative freedom with no real way to assess his achievements outside of his own satisfaction.

Even Jia perhaps loses patience with his subject’s eccentric philosophising, peeling off to follow one of the Thai models on her bus journey home where on turning on her TV set she learns of flooding in her village, neatly mirroring the villagers near Fengjie. Liu tells us that sad things are closer to reality, but Jia paradoxically returns to us to a kind of joy despite the obvious irritation of the model as waiters randomly dance in small cafes before undercutting it with complexity as a pair of blind musicians busk in a busy marketplace, trailing their song with a portable karaoke machine less for the love of it or the art or even the desire to be heard than the desire to be fed.