The contradictions of the modern China drive one young man clear out of his mind in Lv Huizhou’s elliptical street punk noir, Pistol (手枪, Shǒuqiāng). Shot in a washed out monochrome and seemingly set some time after the Beijing Olympics, Lv’s anarchic drama sees its hero develop unexpected superpowers as if to combat his sense of impotence and impossibility while constantly uncertain whether his newfound abilities are “real” or merely a figment of his declining mental state as he chases lost love through the rundown backstreets of a Beijing slum.

Construction worker Mengzi (Zhang Yu) claims he likes Beijing, after all it’s an “international city” always busy with crowds. Many people long to come here, as perhaps he once did, though you can’t say the city has served him particularly well. He lives in a tiny room with a bunk bed and no functioning bathroom which is why he pees in a bottle into which he’s already discarded his cigarette and digs a hole in the woods every time he needs to do a number two. The only thing keeping him going is his doomed relationship with sex worker Yaoyao (Wang Zhener) who just wants to make as much money as she can while she’s young. Mengzi may have stolen the “international city” line from her, he often seems to repeat things said to him when he speaks at all, but Yaoyao also claims to like Beijing because of the opportunities it offers her, citing the story of a woman she knew who quit sex work after only three years with enough money to buy house in her home town, now walking around dripping with jewellery like the queen of all the land. When Yaoyao goes missing, Mengzi fetches up at the salon where she worked that’s really a front for a brothel run by a local gangster and raises hell, picking a fight with the gangster’s wife and in the first of many flashes of spontaneous violence smashing her mirror.

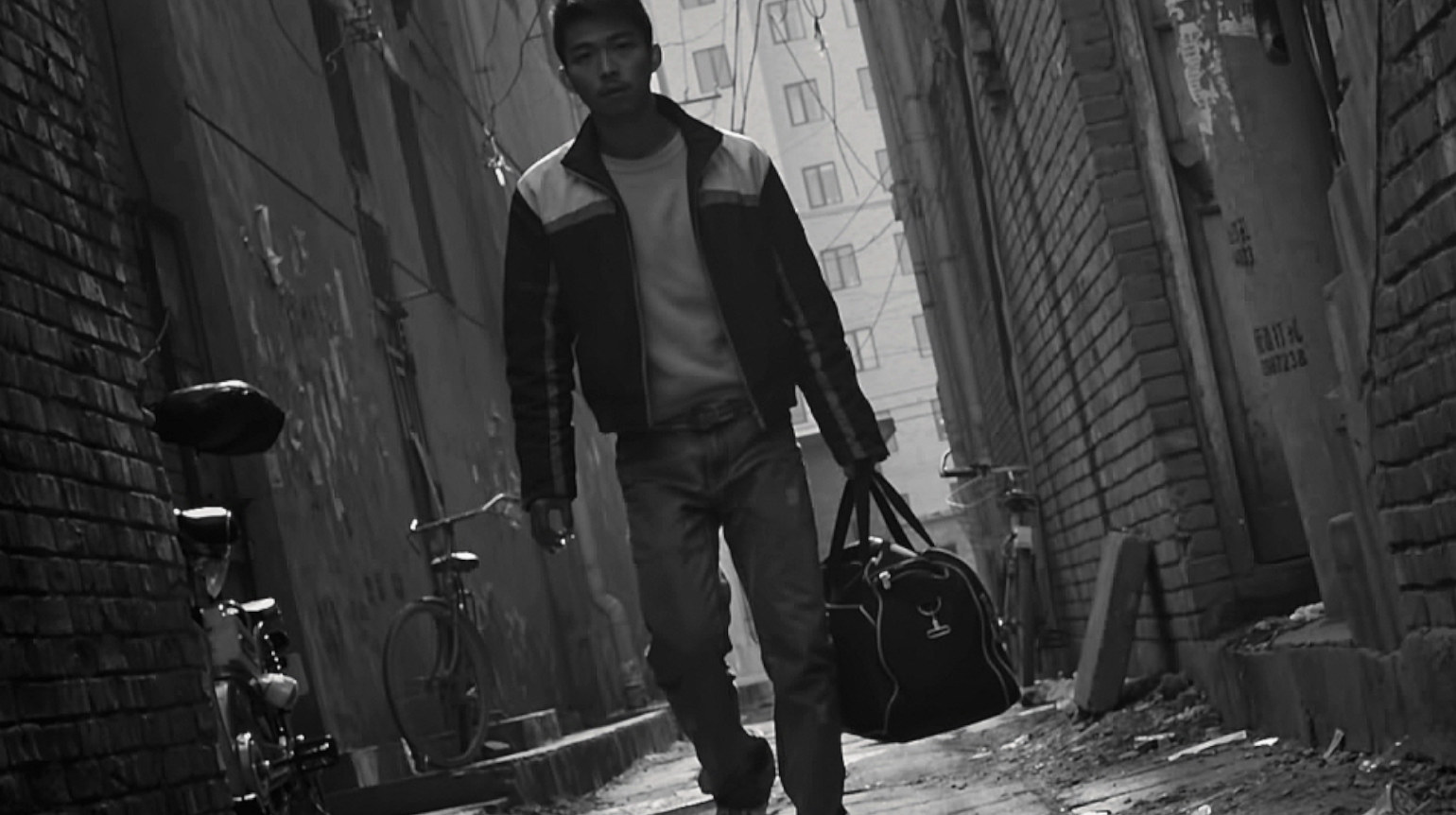

The ill-advised rescue mission gets him nowhere, the gangster turning up at the restaurant where he’s once again adding to his tab to tell him she’s been sold on to a club before teaching him a lesson. This is where we came in, or it might as well be, with Mengzi chased through the narrow city alleyways until finally cornered and beaten. Mengzi is in many ways a man on the run from himself. His room is papered with posters for macho crime dramas such as Dirty Harry, The Man With No Name Trilogy, and A Better Tomorrow 2, Taxi Driver pinned incongruously between boy band Super Junior and a girl group in air hostess outfits. He is God’s lonely man, obsessing over misplacing his high school graduation certificate while failing to convince his boss to give him a better job. At his lowest point, he digs a hole and crouches down pointing his fingers at gaggle of chickens and pretending to shoot only to hear a gunshot and on closer inspection discover a very dead hen.

In the days since losing Yaoyao, Mengzi hadn’t done much of anything save mope around, having a tourist day with streetwise kid Laizi (Hou Xiang) visiting Tiananmen Square and the Olympic stadium, both places Yaoyao lied to her mother about visiting trying to make her think her Beijing life was better than it was. His strange visions and violent meditations are often intercut with comforting memories of his time with Yaoyao alone in her bohemian flat, a poster of Chicken Run ironically hanging on her wall. Flashing into colour, the billboards around the stadium are filled with pretty pink flowers and play the Olympic song about being one big family, red solarised footage of the opening ceremony later filling Mengzi’s mind. Family seems to be something Mengzi doesn’t really have, a perpetual orphan wandering around unanchored and resentful of the society that won’t let him prosper. Losing Yaoyao he vows revenge with his new weapon, which for some reason only works with his rear end partially exposed, literally taking aim at social inequality in the midst of a trendy club from which he concludes he may never be able to retrieve his lost love.

Shot in a washed out black and white reflecting Mengzi’s sense of despair, Lv’s frantic handheld photography mimics his paranoid psychology with its noirish canted angles and extreme sense of claustrophobia while introducing a note of psychedelic uncertainty as even Mengzi himself cannot be sure if his fingers really shoot bullets or he’s in the midst of a psychotic break possibility connected to the traumatic event that opened the film reflected in his own eventual solarisation. An elliptical, ethereal journey through the backstreets of Beijing as they exist in the mind of a crazed young man denied a future and the home he’s so desperate find, Pistol has few kind words for the modern China but perhaps sympathy for its frustrated hero.

Pistol screened as part of this year’s London East Asia Film Festival.