Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project – Thick Walled Room, which dealt with the controversial subject of class C war criminals and was deemed so problematic that it lingered on the shelves for quite some time. Made the same year as the somewhat similar Three Loves, Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky (この広い空のどこかに, Kono Hiroi Sora no Dokoka ni) is a fairly typical contemporary drama of ordinary people attempting to live in the new and ever changing post-war world, yet it also subtly hints at Kobayashi’s ongoing humanist preoccupations in its conflict between the idealistic young student Noboru and his practically minded (yet kind hearted) older brother.

Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project – Thick Walled Room, which dealt with the controversial subject of class C war criminals and was deemed so problematic that it lingered on the shelves for quite some time. Made the same year as the somewhat similar Three Loves, Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky (この広い空のどこかに, Kono Hiroi Sora no Dokoka ni) is a fairly typical contemporary drama of ordinary people attempting to live in the new and ever changing post-war world, yet it also subtly hints at Kobayashi’s ongoing humanist preoccupations in its conflict between the idealistic young student Noboru and his practically minded (yet kind hearted) older brother.

The Moritas own the liquor store in this tiny corner of Ginza, where oldest brother Ryoichi (Keiji Sada) has recently married country girl Hiroko (Yoshiko Kuga). The household consists of mother-in-law Shige (Kumeko Urabe), step-mother to Ryoichi, unmarried sister Yasuko (Hideko Takamine), and student younger brother Noboru (Akira Ishihama). Things are actually going pretty well for the family, they aren’t rich but the store is prospering and they’re mostly happy enough – except when they aren’t. Ryoichi married for love, but his step-mother and sister aren’t always as convinced by his choice as he is, despite Hiroko’s friendly nature and constant attempts to fit in.

As if to signal the dividing wall between the generations, Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky opens with a discussion between two older women, each complaining about their daughters-in-law and the fact that their sons married for love rather than agreeing to an arranged marriage as was common in their day. These love matches, they claim, have unbalanced the family dynamic, giving the new wife undue powers against the matriarchal figure of the mother-in-law. While the other woman’s main complaint is that her son’s wife is absent minded and bossy, Shige seems to have little to complain about bar Hiroko’s slow progress with becoming used to the runnings of the shop.

Despite this, both women appear somewhat hostile towards Ryoichi’s new wife, often making her new home an uncomfortable place for her to be. Though Hiroko is keen to pitch in with the shop and the housework, Shige often refuses her help and is preoccupied with trying to get the depressed Yasuko to do her fair share instead. At 28 years old, Yasuko has resigned herself to a life of single suffering, believing it will now be impossible for her to make a good a match. Yasuko had been engaged to a man she loved before the war but when he returned and discovered that she now walks with a pronounced limp following an injury during an air raid, he left her flat with a broken heart. Embittered and having internalised intense shame over her physical disability, Yasuko finds the figure of her new sister-in-law a difficult reminder of the life she will never have.

A crisis approaches when an old friend (and perhaps former flame) arrives from Hiroko’s hometown and raises the prospect of abandoning her young marriage to return home instead. No matter how her new relatives make her feel, Hiroko is very much in love with Ryoichi and has no desire to leave him. Thankfully, Ryoichi is a kind and understanding man who can see how difficult the other women in the house are making things for his new wife and is willing to be patient and trust Hiroko to make what she feels is the right decision.

Ryoichi’s talent for tolerance is seemingly infinite in his desire to run a harmonious household. However, he, unlike younger brother Noboru, is of a slightly older generation with a practical mindset rather than an idealistic one. Ryoichi simply wants to prosper and ensure a happy and healthy life for himself and his family. This doesn’t mean he’s averse to helping others and is actually a very kind and decent person, but he is quick to point out that he needs to help himself first. Thus he comes into conflict with little brother Noburu from whom the film’s title comes.

Noburu is a dreamer, apt to look up at the wide sky as symbol of his boundless dreams. His fortunes are contrasted with the far less fortunate fellow student Mitsui (Masami Taura), who comes from a much less prosperous and harmonious family, finding himself working five different jobs just to eat twice a day and study when he can. Noburu wants to believe in a brighter world where things like his sister’s disability would be irrelevant and something could be done to help people like Mitsui who are struggling to get by when others have it so good. Ryoichi thinks this is all very well, but it’s pie in the sky thinking and when push comes to shove you have to respect “the natural order of things”. Ryoichi wants to work within the system and even prosper by it, where as Noburu, perhaps like Kobayashi himself, would prefer that the “natural order of things” became an obsolete way of thinking.

Nevertheless, it is the power of kindness which cures all. Gloomy Yasuko begins to live again after re-encountering an old school friend and being able to help her when she is most in of need of it. Being of use after all helps her put thoughts of her disability to the back of her mind and so, after hiding from a man who’d loved her in the past out of fearing his reaction to her current state (and overhearing his general indifference on hearing of it), she makes the bold decision to strike out for love and the chance of happiness in the beautiful, yet challenging, mountain environment.

Like many films of the era, Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky is invested in demonstrating that life may be hard at times, but it will get better and the important thing is to find happiness wherever it presents itself. This is not quite the message Kobayashi was keen on delivering in his subsequent career which calls for a more circumspect examination of contemporary society along with a need for greater personal responsibility for creating a kinder, fairer and more honest one. A much more straightforward exercise, Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky is Kobayashi channeling Kinoshita but minimising his sentimentality. Nevertheless, it does present a warm tale of a family finally coming together as its central couple prepares to pick up the reins and ride on into the sometimes difficult but also full of possibility post-war world.

Masaki Kobayashi is still not enamoured with the new Japan by the time he comes to make Black River (黒い河, Kuroi Kawa) in 1957 which proves his most raw and cynical take on contemporary society to date. Set in a small, rundown backwater filled with the desperate and hopeless, Black River is a tale of ruined innocence, opportunistic fury and a nation losing its way.

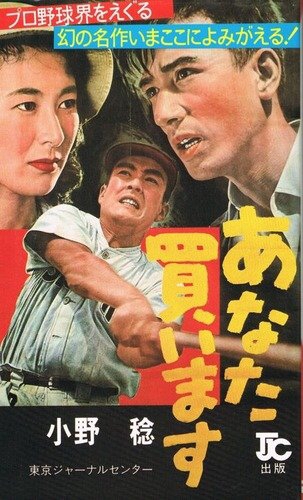

Masaki Kobayashi is still not enamoured with the new Japan by the time he comes to make Black River (黒い河, Kuroi Kawa) in 1957 which proves his most raw and cynical take on contemporary society to date. Set in a small, rundown backwater filled with the desperate and hopeless, Black River is a tale of ruined innocence, opportunistic fury and a nation losing its way. In I will Buy You (あなた買います, Anata Kaimasu, a provocative title if there ever was one), Kobayashi may have moved away from directly referencing the war but he’s still far from happy with the state of his nation. Taking what should be a light hearted topic of a much loved sport which is assumed to bring joy and happiness to a hard working nation, I Will Buy You exposes the veniality not only of the baseball industry but by implication the society as a whole.

In I will Buy You (あなた買います, Anata Kaimasu, a provocative title if there ever was one), Kobayashi may have moved away from directly referencing the war but he’s still far from happy with the state of his nation. Taking what should be a light hearted topic of a much loved sport which is assumed to bring joy and happiness to a hard working nation, I Will Buy You exposes the veniality not only of the baseball industry but by implication the society as a whole. There’s a persistent myth that Japanese cinema avoids talking about the war directly and only addresses the war part of post-war malaise obliquely but if you look at the cinema of the early ‘50s immediately after the end of the occupation this is not the case at all. Though the strict censorship measures in place during the occupation often made referring to the war itself, the rise of militarism in the ‘30s or the American presence after the war’s end impossible, once these measures were relaxed a number of film directors who had direct experience with the conflict began to address what they felt about modern Japan. One of these directors was Masaki Kobayashi whose trilogy, The Human Condition, would come to be the best example of these films. This early effort, The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋, Kabe Atsuki Heya), scripted by Kobo Abe is one of the first attempts to tell the story of the men who’d returned from overseas bringing a troubled legacy with them.

There’s a persistent myth that Japanese cinema avoids talking about the war directly and only addresses the war part of post-war malaise obliquely but if you look at the cinema of the early ‘50s immediately after the end of the occupation this is not the case at all. Though the strict censorship measures in place during the occupation often made referring to the war itself, the rise of militarism in the ‘30s or the American presence after the war’s end impossible, once these measures were relaxed a number of film directors who had direct experience with the conflict began to address what they felt about modern Japan. One of these directors was Masaki Kobayashi whose trilogy, The Human Condition, would come to be the best example of these films. This early effort, The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋, Kabe Atsuki Heya), scripted by Kobo Abe is one of the first attempts to tell the story of the men who’d returned from overseas bringing a troubled legacy with them.