By the mid-1950s, Japan’s economy was beginning to improve but now that the desperation that went with hunger had dissipated it freed those who’d managed to climb out of post-war privation to wonder just what the point of their ceaseless toil was. Yasujiro Ozu’s primary subject matter remained the modern family, but 1956’s Early Spring (早春, Soshun) sees him heading in a darker direction as he weighs up the delusions of the salaryman dream and discovers that whichever way you swing it, life is disappointing.

So it seems to be for salaryman Shoji (Ryo Ikebe). He and Masako (Chikage Awashima) married for love a long time ago, but it’s clear that there is distance in their relationship. They sleep in the same room but their futons are slightly too far apart, and the few words they exchange with each other in the morning are terse in the extreme. The truth is that for many a salaryman for whom long hours and interoffice bonding sessions are compulsory, work is the new family. Wives are welcome to join the Sunday hiking outings but it seems few do. Masako too declines, telling her mother she felt it to be too expensive, already irritated with her husband’s irresponsible spending on mahjong games and drinking with friends.

Money is certainly a constant worry for her and as we learn from her mother they’re behind on the rent despite it being “very cheap”. Masako had made a visit home in part to ask for another loan, which her mother seems reluctant to give, offering her daughter a takeout of the oden her restaurant sells which is first declined but then accepted. Her mother also flags up the other problem in their marriage which is that they sadly lost a child in infancy and have had no more. Sorrow may have killed their love, but the fact her husband stays out all hours and wastes the little money he earns while failing to win promotions only makes the situation worse.

As for Shoji, he is becoming very aware of the delusions of the “salaryman dream”. He is one of thousands of men identically dressed in white shirts and grey trousers that board the packed rush hour trains every day heading into the city. His life is one of pointless drudgery and its only victory is that keeps hunger from the door, not even quite stretching to a roof over his head. “All that’s waiting for us is disillusion and loneliness” according to a veteran salaryman growing close to his retirement and realising that he has little left to live on, his dream of buying a small stationary shop all but unobtainable. He was dead set against his own son joining the ranks of the salaryman, but in the end failed to prevent it.

It is perhaps this sense of frustration and impotence that draws Shoji into an affair with a younger woman, Chiyo (Keiko Kishi), who is admittedly very pretty but seems to hold little interest for him aside from her youth and beauty. Chiyo openly pursues her older colleague, declaring that she doesn’t care he has a wife but has come to hate her after the first time they slept together. Shoji meanwhile remains guilty and conflicted. He evidently continues seeing Chiyo, lying to Masako that he’s visiting a sick friend, but otherwise regards her as an irritation. When his co-workers figure out what’s going on they try to stage an intervention, but Shoji doesn’t show up and Chiyo angrily denies everything before arriving at Masako’s looking for Shoji only this time he really is out visiting a sick friend.

Miura (Junji Masuda), the sick friend, is a true believer in the salaryman dream. Now that he’s ill, he misses the packed trains and elevators, not to mention his old workplace friends. All he wants is to be well enough to return to the office and his predicament perhaps has Shoji thinking that at least he has his health and things aren’t so bad for him after all. Masako, meanwhile, turns to other women for advice. The woman across the way recounts how she caught her husband out with his mistress and made a scene that’s rendered him docile and obedient ever since (a rare man in an Ozu film putting his socks neatly in the laundry basket and hanging up his own coat rather than throwing it on the floor for his wife to deal with). Her widowed friend is more sanguine, admitting that caution is necessary but it’s a little dark to envy the life of a widow for its “freedom”, while her mother thinks she’s overreacting because that’s just how men are in this generation or any other.

Shoji’s old mentor agrees that “everyone’s disappointed” and all that remains is to try and make the most of it, but still he sees that Shoji has been reckless and inconsiderate in his treatment of both women. He avoids his wife because of the emotional distance between them born of grief, and only really has an affair with Chiyo because it was easier than refusing her. He didn’t even enjoy it, and doubtless it did not quite quell the sense of despair he feels with the utter pointlessness of the “salaryman dream”. Masako, in turn, is disappointed with married life, with her husband’s emotional cowardice, and with her own lack of options. Ultimately, Ozu sides with the mother, not quite condoning Shoji’s behaviour while perhaps excusing it as a direct consequence of dullness of his life while forcing Masako to accept complicity in her husband’s weakness. They may reunite, the stressors of their Tokyo life from the high cost of living to the lure of mahjong now absent, but there is a sense of futility in their eventual insistence that they will “make it work” through starting over in a new place while gazing at the train that, they assume, will eventually carry them back to the city and all of its false promises of a brighter future.

Early Spring screens 19th/20th/21st October & 20th/23rd November at London’s BFI Southbank as part of BFI Japan. It is also available to stream in the UK via BFI Player and in the US via Criterion Channel.

In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger.

In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger. Although Masahiro Shinoda has long been admitted into the pantheon of Japanese New Wave masters, he is mostly remembered only for his 1969 adaptation of a Chikamatsu play, Double Suicide. Less overtly political than many of his contemporaries during the heady years of protest and rebellion, Shinoda was a consummate stylist whose films aimed to dazzle with visual flair or often to deliberately disorientate with their worlds of constant uncertainty. Like so many of the directors who would go on to form what would retrospectively become known as the Japanese New Wave, Shinoda also started out as a junior AD, in this case at Shochiku where he felt himself stifled by the studio’s famously safe, inoffensive approach to filmmaking.

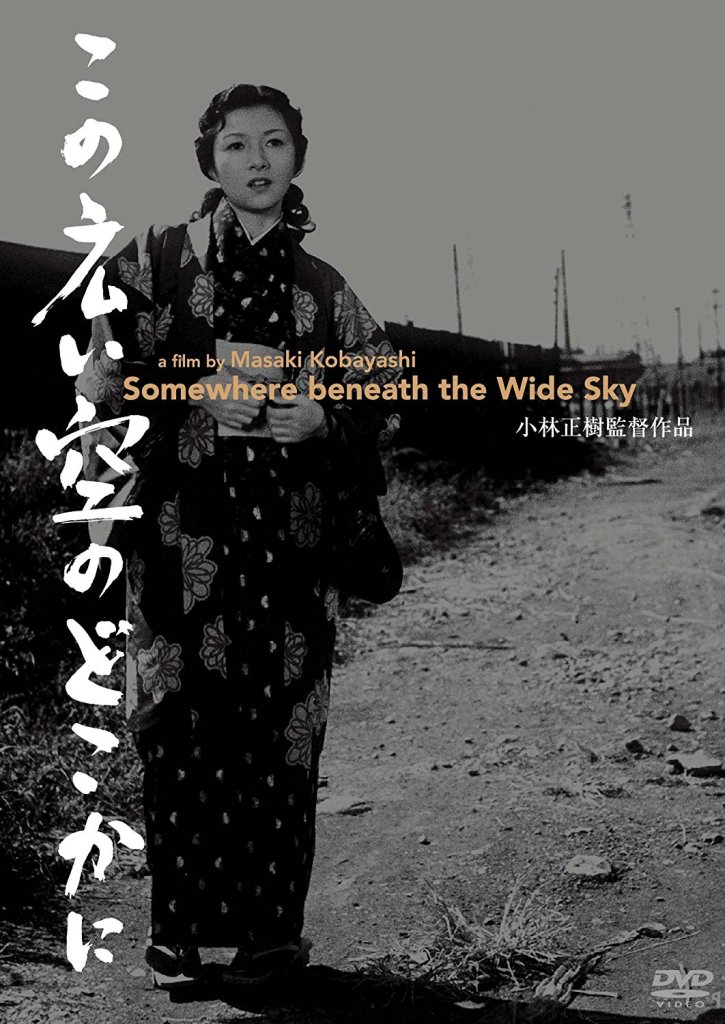

Although Masahiro Shinoda has long been admitted into the pantheon of Japanese New Wave masters, he is mostly remembered only for his 1969 adaptation of a Chikamatsu play, Double Suicide. Less overtly political than many of his contemporaries during the heady years of protest and rebellion, Shinoda was a consummate stylist whose films aimed to dazzle with visual flair or often to deliberately disorientate with their worlds of constant uncertainty. Like so many of the directors who would go on to form what would retrospectively become known as the Japanese New Wave, Shinoda also started out as a junior AD, in this case at Shochiku where he felt himself stifled by the studio’s famously safe, inoffensive approach to filmmaking. Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project –

Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project –