“That place is filled with horror and mystery” a creepily persistent man on a train claiming to be a clairvoyant warns the new governess to a home that does indeed turn out to be tinged with tragedy, though in true gothic melodrama fashion that was something of which she was already well aware. Inspired by the Victoria Holt novel Mistress of Mellyn, Taiyupian The Bride Who Has Returned From Hell (地獄新娘) is less supernatural mystery than eerie romance which sees frustrated desire collide with outdated social mores to destabilise the social order in the otherwise tranquil world of the new elite.

Echoing the novel’s Cornish atmospherics, the opening title sequence pans over the rugged coastal landscape with its rocky outcrops and crashing waves before homing in on a policeman picking up a handbag while his colleagues investigate the body of a man drowned at sea. Meanwhile, wealthy entrepreneur Yi-Ming (Ko Chun-Hsiung) is worried because his wife Sui-Han is not at home despite the fact they’re supposed to be going to a friend’s birthday party. The man’s body is identified as Guo Jing-Min, Yi-Ming’s cousin and the older brother of the woman living next-door, Feng-Jiao (Liu Ching). Jing-Min and Sui-Han were once lovers, and given that the handbag appears to have been hers, it’s assumed that the pair attempted to elope but got into trouble and drowned with Sui-Han’s body possibly lost at sea.

Perhaps tellingly, Yi-Ming’s reaction to his wife’s disappearance is irritation and suspicion. He asks the housekeeper if Sui-Han has ever stayed out all night while he’s away from home and on learning that she may have come to harm focuses solely on the embarrassment of being a man whose wife has betrayed him. “How am I supposed to face people?” he angrily asks Feng-Jiao who apologises on her brother’s behalf (but seems equally unperturbed at his demise). He more or less gives up on finding out what’s happened to Sui-Han and begins to reject his daughter, Su-Luan, solely because she reminds him of his wife while taking up with another woman, Mrs Lian (Kuo Yeh-Jen), who married a much older man presumably for his money.

Meanwhile, Sui-Mi (Chin Mei), Sui-Han’s sister who has recently returned to Taiwan after many years living abroad in Singapore, has secretly taken a job as a governess in the Wang household under an assumed name in order to investigate her sister’s disappearance. The man on the train who warned her about the house’s dark mystery, the lonely little girl, and the man with a bad reputation turns out to be none other than the other brother of Feng-Jiao who lives with her in a neighbouring mansion. Apparently employed partly because of her physical similarity to the (presumed) late Sui-Han in an effort to provide comfort to the highly strung Su-Luan, Sui-Mi is only one of several doubles in play which include the decidedly creepy little girl Lan (Dai Pei-shan), the housekeeper’s granddaughter, who insists that Sui-Han is still alive while more or less spying on everyone making full use of her invisibility as a member of the servant class.

Like any heroine of a gothic romance, Sui-Mi’s role is not just to solve the mystery but to restore order by unifying the various forces of destabilisation currently threatening the Wang family which is one reason we see her actively include Lan, treating her the same as she does Su-Luan, teaching the two girls to be friends and equals as she educates them both together. The other threat to social harmony is in Yi-Ming’s moodiness and womanising, most particularly his possibly immoral relationship with Mrs. Lian and inability to embrace his role as a father by showing love to his daughter who is already becoming strange and neurotic in the wake of her mother’s death, believing that she has been abandoned by both parents. Thus, partly thanks to her physical similarity to Sui-Han as her sister, Sui-Mi assumes the maternal role assuring Su-Luan that she will love her forever in her mother’s place while Yi-Ming’s growing attraction to her precisely because of these maternal qualities, in its own way also problematic, draws him back towards the proper path of home and family.

Pursued by Feng-Jiao’s creepy brother and conflicted in her attraction to her brother-in-law while still harbouring the suspicion he may be involved in her sister’s disappearance, Sui-Mi finds herself drifting away from the idea of solving the mystery even while inhabiting the creepy mansion which is in its own way both literally and figuratively haunted. A dream apparition of her sister in an ethereal use of double exposure effectively gives her permission to pursue her romantic destiny by instructing her to stay in Taiwan and look after Su-Luan because, she fears, no one else will which doesn’t speak highly of Yi-Ming, while reminding Sui-Mi that she came to the Wangs’ for a reason.

“You can’t get true love by manipulation” the villain is later told, revealing to us that the motive in this case really was romantic jealousy, a typically gothic sense of repression born of oppressive patriarchal social codes which prevent the proper expression of desire and eventually lead to violence. Sui-Mi restores order by solving the mystery and then healing the rifts by, ironically, submitting herself to those same oppressive social codes in assuming her “natural” role as wife and mother. Using a series of unexpected music cues from ominous Japanese folksong Moon over Ruined Castle as Sui-Mi surveys the rugged mansion to the more upbeat Hana as she plays with the children, moody jazz, Danny Boy, and even the James Bond theme playing over the climax (not to mention the many instances of child star and producer’s daughter Dai Pei-shan singing her gloomy lullaby), Hsin goes all in on the gothic imagery even having Sui-Mi almost fall victim to a suspicious rock fall just as she becomes a credible romantic heroine, before ending on a cheerful note with another song celebrating the simple joys of the traditional family.

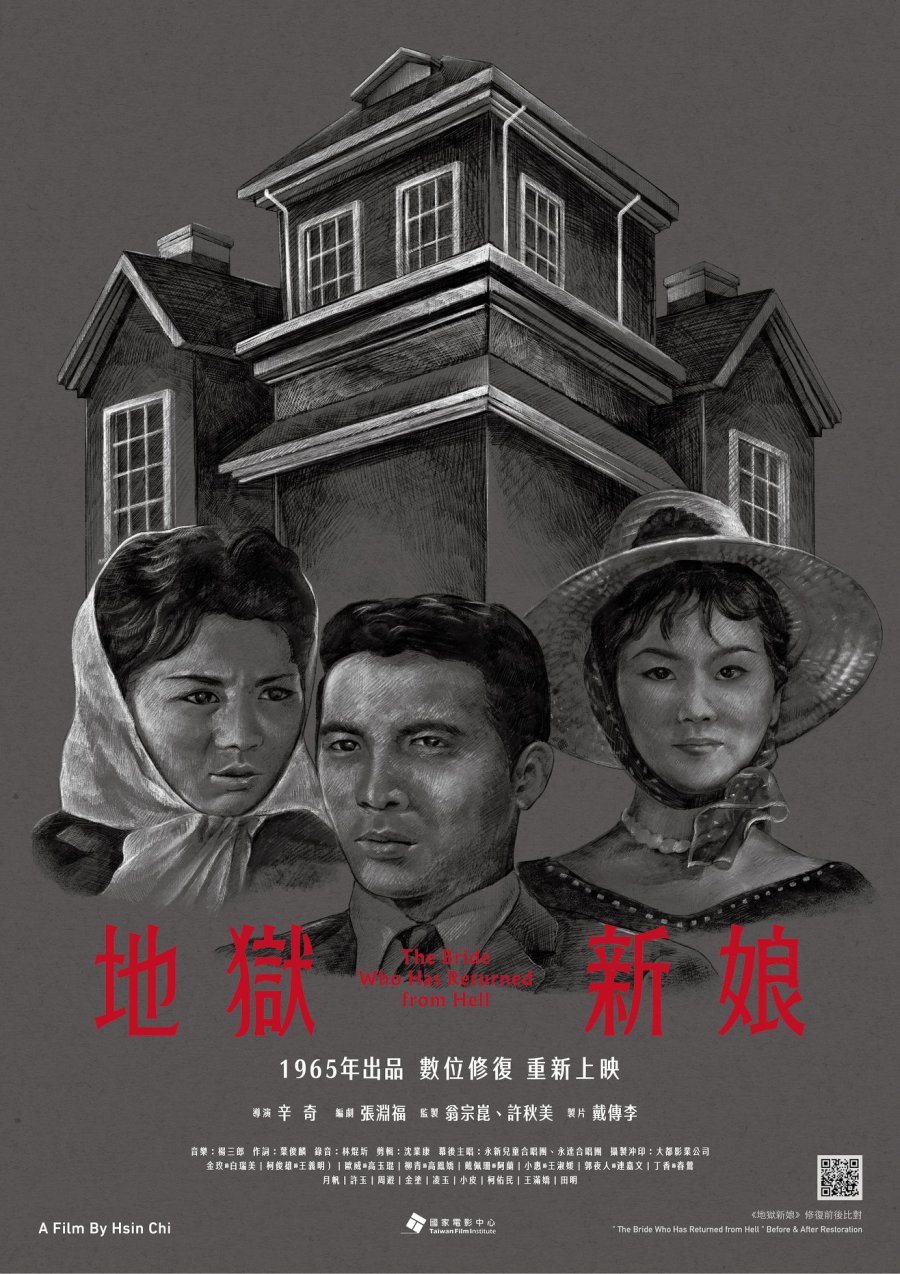

The Bride Who Has Returned From Hell streams in the UK until 27th September as part of the Taiwan Film Festival Edinburgh.

Restoration trailer (English subtitles)