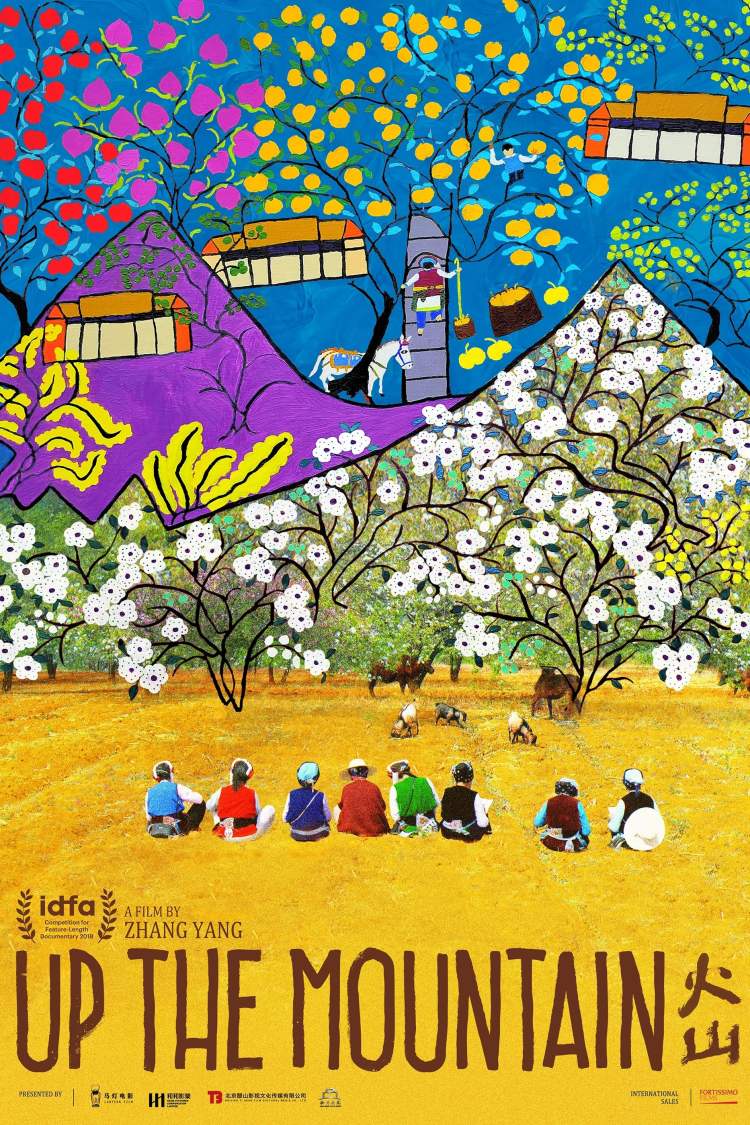

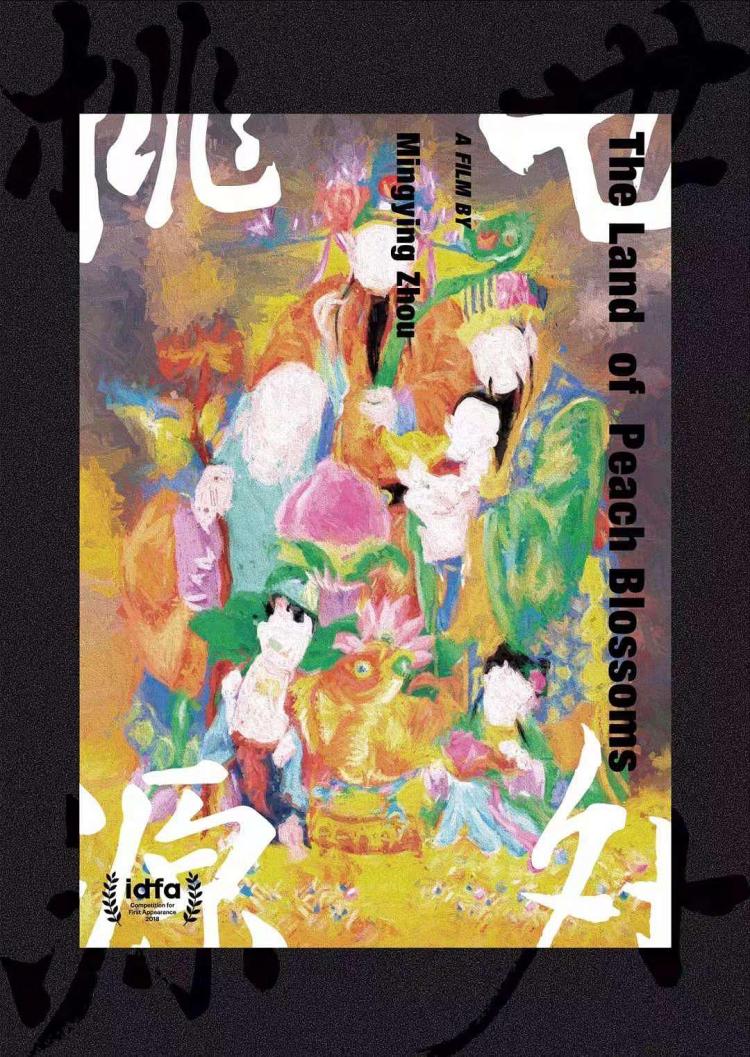

In Tao Yuanming’s 5th century fable, The Land of Peach Blossoms (世外桃源, Shìwàitáoyuán) is a mythical utopia where people live in peace and harmony knowing nothing of the outside world. Zhang Derong, the founder of the Feast of Flowers restaurant, saw himself as creating something similar – a place beyond the outside world founded on collectivist principles where they make healthy people healthier through “emotional catering”. If it were not immediately obvious, the founder of Feast of Flowers is not entirely on the level but has promised great things to the young men who work in his restaurant and look up to him as if he were some kind of more ethical, caring Jack Ma.

In Tao Yuanming’s 5th century fable, The Land of Peach Blossoms (世外桃源, Shìwàitáoyuán) is a mythical utopia where people live in peace and harmony knowing nothing of the outside world. Zhang Derong, the founder of the Feast of Flowers restaurant, saw himself as creating something similar – a place beyond the outside world founded on collectivist principles where they make healthy people healthier through “emotional catering”. If it were not immediately obvious, the founder of Feast of Flowers is not entirely on the level but has promised great things to the young men who work in his restaurant and look up to him as if he were some kind of more ethical, caring Jack Ma.

His most devoted pupil, Tang Guangbin used to work in a nuclear power plant and had a sea view from his company dorm but he likes it here better because he feels “free” in his heart and soul. Like Guangbin, Zeng Qi also feels that as long as they follow The President’s teachings they will make the Feast of Flowers bloom all around the world spreading health and happiness as they go. The Feast of Flowers is indeed a cheerful place filled with dancing and a faux ancient fantasy Chinese village atmosphere. There is also, however, a dark side which will become apparent to the young hopefuls the longer they stay in the garden.

The truth becomes apparent first to the practically minded Wang Peiyuan who turned down more lucrative jobs to work at the Feast of Flowers because he bought into Zhang’s ambitious business plan and assumed there would be more opportunities down the line. Not only is his pay cheque lower than promised because of all the “training” he has to pay for, but it’s so far below market rate that he’s worrying about paying his mortgage and being able to feed his wife and child. Meanwhile, Zhang waxes lyrical about work ethics and insists that “training” his workforce until 5am and then starting again at 8 is all part of his grand plan to turn them into top entrepreneurs.

Guangbin excuses himself to a friend on the phone in case he sounds as if he’s been “brainwashed” as he fiercely sells Zhang’s philosophy as not only a way to become rich and successful but to make the world a better, more caring place – the kind of place he perhaps assumes China was before the ‘80s reforms which opened it up to Capitalism. Of course, Guangbin is too young to remember what it was like back in the ‘70s, but hears people tell him about solidarity and job security and he’s understandably envious. He’s made a big investment in Feast of Flowers and so it takes a long time before he’s prepared to accept that he is being exploited by an unscrupulous charlatan. Once he and some of the other guys figure out there won’t be any expansion of Feast of Flowers, prime jobs, or bonuses, they want to quit but they can’t because they’re in hock for all this “training” and will lose their unpaid salary because, ironically, they don’t have effective work place protections.

Zhang runs the place as if it were a work cadre and himself the Chairman. He commands absolute loyalty and requires employees to self criticise, running regular hunts to find the most “self centred” of the workers with many keen to jump at the bait and even to accuse others on cue. Those who disagree and want to leave are dismissed as having “too many personal thoughts and opinions” when they should be concentrating on understanding The President’s philosophy. Guangbin once felt free inside the Feast of Flowers, but later came to feel that outside was “a world of freedom” and inside “a prison full of darkness” from which there is “no escape”.

As if to ram his point home, Zhang makes the workers listen to Red Detachment of Women and has a bizarre obsession with “retaking” the Diaoyu Islands (also known Senkaku islands) from the Japanese, even staging a surreal play in which the Feast of Flowers soldiers personally defeat the Japanese army and capture Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe while Moon Over Ruined Castle plays mournfully in the background. Disillusioned by modern China’s lurch towards soulless consumerism and yearning for a simpler time in which people supported each other in common endeavour (but secretly still wanting to get ahead), the youngsters at Feast of Flowers bought into Zhang’s duplicitous nonsense and allowed themselves to be brainwashed into serving his ideals rather than their own. The parallels are obvious, but Guangbin may sadly be right in believing that there is no escape from the soul crushing exploitation of the modern economy which promises so much and yet delivers so little.

The Land of Peach Blossoms screens as part of the 2019 Chinese Visual Festival at King’s College London on 5th May, 7.15pm.

Original trailer (English subtitles)