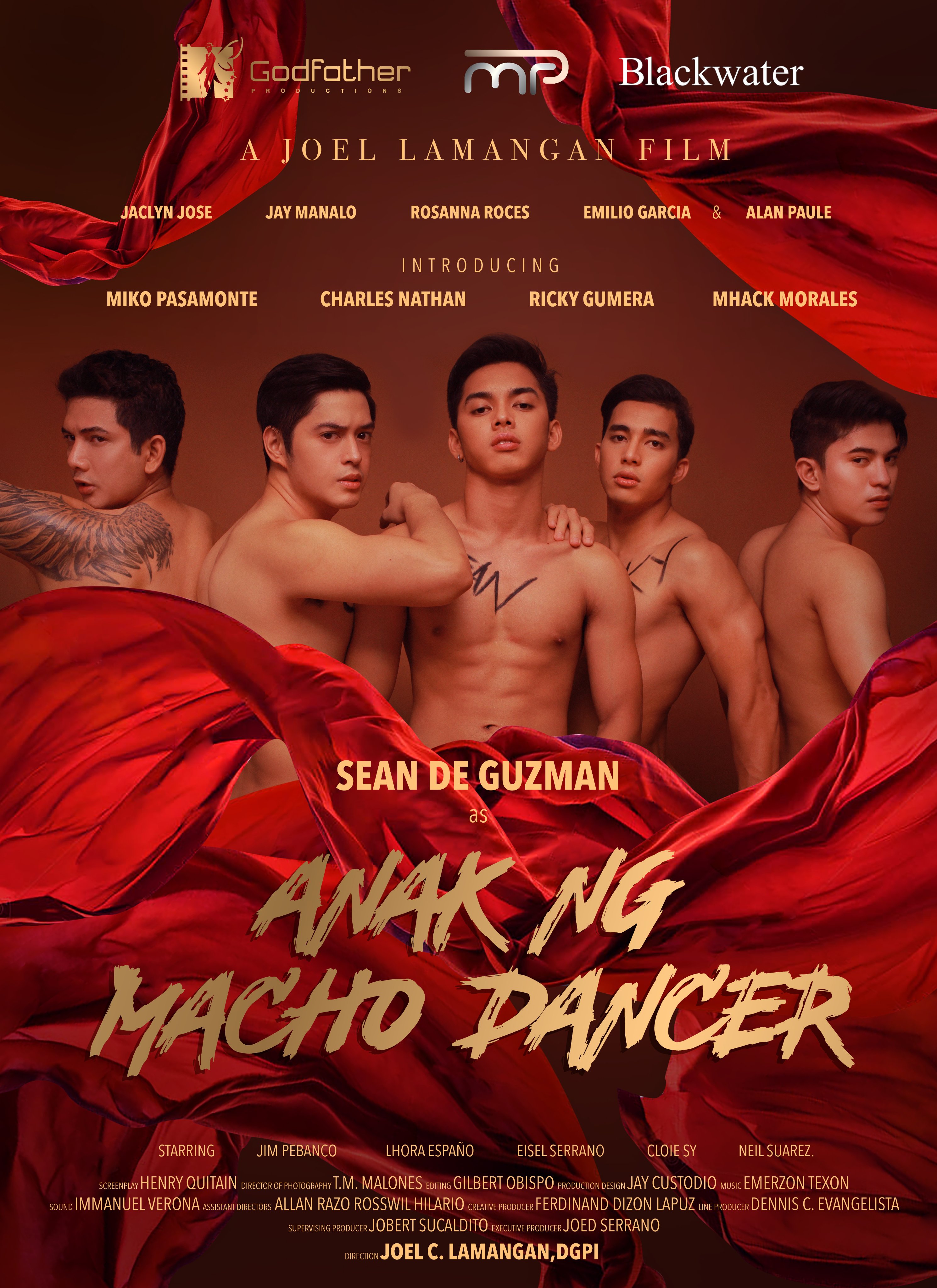

“How many have you buried? Why?!” asks the hero of Joel Lamangan’s Son of the Macho Dancer (Anak ng macho dancer), a quasi sequel to the 1988 Lino Brocka classic. Set during the early days of the pandemic, Lamangan’s salty drama hints at the radiating effects of an authoritarian culture for those living on the margins of the contemporary society but does so with a dose of trashy telenovela camp in its eventually redemptive tale of frustrated futures, sexual exploitation, drugs and murder in a time of increasing sickness.

19-year-old Inno (Sean De Guzman) is in a casual relationship with a woman whose tendency to refer to herself as his girlfriend clearly irritates him, especially as their sex life seems to be frustrated by her fear of his apparently giant penis. When his father Pol (Allan Paule) who has become addicted to drugs after a car accident is arrested by the police and he needs money to bail him out, Inno’s mother (Rosanna Roces) seizes on his oversize appendage as a means of saving the family by dragging him straight to a local gay club to become a go-go dancer. While reluctant at first, Inno soon takes to his new life and decides to milk it for all its worth, latching on to VIP procurer Bambi (Jaclyn Jose) and her sidekick Roldan (Emilio Garcia) in the hope of being invited to one of their elite parties all of which later drags him into the orbit of sadistic gay drug dealer Jun (Jay Manalo).

All the while, we see Duterte on TV giving updates in the corona virus crisis and the various measures to mitigate it which threaten the survival of gay bar Mankind as well as the illicit business enterprises operated by Jun, Bambi, and Roldan. A police officer reconfirms his warning to drug dealers that they shouldn’t expect an easy ride during the pandemic because they will “destroy all of you”. The police force is shown to be resolutely corrupt, firstly in its refusal to investigate the causes of the car crash which caused Pol’s descent into addiction because, he believes, the driver was a judge and the cops have been paid off, and lastly in its complicity with criminal activity as evidenced in their cooperation with Roldan to cover up his crimes.

Obsessed with social media clout, Inno constantly documents and uploads his existence online marvelling at his new circumstances as a kept man of Jun only latterly reflecting on the ironies of his life in discovering that his father was once also a “macho dancer” while his mother was forced to turn to sex work to feed the family after Pol’s accident. Seduced by the lifestyle of the rich and powerful that Jun can give him he doesn’t stop to consider its wider implications even when warned by predecessor Kyle (Ricky Gumera) of the dangerously oppressive regime within the house. It’s not until he finds himself burying the body of a friend murdered by Jun after unwittingly failing to play along with his voyeuristic sexual fantasies that he begins to ask why, not only why he’s living this life but why Bambi has been living it all this time enabling Jun’s predatory violence in burying the bodies of unlucky young men who fell foul of his sadistic desires.

For Kyle at least the answer may be a lifetime of violent abuse which which has left him too traumatised to believe escape is possible. Inno vacillates between resentment towards his father for his irresponsible drug use and mistreatment of his long-suffering mother, and the filial desire to protect him which led him to become a macho dancer in the first place. Bambi and Pol, meanwhile, the heroes of Brocka’s film have been consistently brutalised by an oppressive society apparently only awakened to the possibility of changing course by Inno’s corrective questioning.

In any case, there’s a minor irony even in the wilful subversion of positioning the young hero as a sex object valued only for the size of his penis while the frequent full frontal male nudity often feels gratuitous and the final swing towards heteronormativity can’t help but align homosexuality with the psychopathic cruelty of Jun as something dark and perverse even while ending on a joyous if tempered moment of resilience in returning to Mankind with the house full of masked clubbers continuing to shove their notes into the dancers’ briefs. Though the final resolution may in a sense be too neat, a family restoring or remaking itself in the wake of trauma, Lamangan allows the sense of unease to continue in the callback to societal corruption as the ongoing pandemic seems to stand in for other kinds of increasing sickness.

Son of the Macho Dancer streams worldwide until 2nd July as part of this year’s hybrid edition Udine Far East Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)